Answering the calls of the wild

Fox in the yard? Bat in the bedroom? Injured bird in the road? No call is too small for the Animal Welfare League of Arlington

As cars zoom past the sidewalk where she’s kneeling, Jennifer Toussaint carefully lifts a pigeon, cradling him in her hands and stroking his head, then raises his wing to feel beneath his feathers. “He’s beautiful,” she says, gently squeezing the bird’s chest to assess his body fat. One by one, she’s checking off items on her mental list. Weight? Normal. Broken bones? It doesn’t appear so. Eye damage? His right eye blinks alertly, but his left one isn’t keeping up. “You can see it’s a little bit bloodshot,” Toussaint says. All signs point toward an acute injury, she adds, “so we’re going to take him in.”

Back at her truck, Toussaint prepares a shoebox to safely transport her latest patient to the Animal Welfare League of Arlington, Virginia, where she is chief animal control officer. She tucks the towel into the spaces around him—an extra security blanket to keep him safe during the ride.

Running east toward the Potomac River, Lee Highway is treacherous for humans even on a good day. But at rush hour in the rain, the roads radiating from the nation’s capital can be especially deadly for wildlife. Among the thousands of commuters are animals trying to go about their lives too. Arlington County is home to snakes, bats, turtles, opossums, deer and even bald eagles sharing space with an ever-growing human population: At only 26 square miles, with 234,000 people and counting, it’s one of the most densely packed jurisdictions in the U.S.

Many animals thrive here: industrious raccoons who don’t mind substituting a chimney for a tree cavity; foxes who dine on rodents and rabbits; squirrels capable of Olympic-style acrobatics around backyard bird feeders. Some of their human neighbors are surprised by the behaviors of local wildlife, some frightened, and some delighted. But no matter the question or complaint, Toussaint sees it as her job to respond to all of them—for the good of both the animals and the community.

“Thank goodness she called,” she says of the resident who took the time to move the injured pigeon out of the road and dial AWLA for help. “It’s going to get chillier, and he would have been struck again or just sat there and expired.”

Now he’ll rest in a quiet holding room for wildlife, while another animal helped by Toussaint—a Weimaraner named Nixon who’d been abandoned in an empty apartment without food—regains his strength in the kennels. Though most shelters focus on the needs of dogs, cats and small pets, Toussaint and her colleagues view the pigeon’s needs as equally important. Increasingly, the county’s residents do too, looking to AWLA to provide assistance and support for all animals, both domestic and wild. That’s why staff have worked so hard to establish relationships with a network of wildlife rehabilitators. It’s why they’ve partnered with county nurses to develop protocols that save bats and other rabies-vector species from unnecessary euthanasia. And it’s why they signed the pledge to become a Humane Society of the United States Wild Neighbors community, dedicated to resolving human-wildlife conflicts effectively and humanely.

Toussaint started this day in a courtroom, where she successfully argued for custody of Nixon so he can be adopted by a loving family. She’s winding it down by microwaving a rice-filled sock, which she adds to the pigeon’s shoebox for warmth. Both tasks help an animal in distress, and address a public demand that would otherwise go unfulfilled. “My community loves animals. They want them to be treated a certain way. It’s not a large leap to think that they’d want wildlife to be treated with the same level of respect or dedication,” says Toussaint. “And we know they do because our calls for service show that they do—we get more wildlife calls than we get stray animal calls.”

Of the nearly 3,400 calls for service each year to AWLA, about half are related to wildlife. In one month, wildlife calls exceeded all others—including those for strays, bites and cruelty—combined. “I feel adamant about answering your community’s needs,” Toussaint says. “And if I’m not the person who’s supposed to do this, who is?”

Help! There’s a fox in my yard

The phone rings in animal control services coordinator Anna Barrett’s office. This time it’s not a report of an injured bird— the most common call she receives. This call is from a resident who’s been watching a fox on his property.

“He’s been hanging out in our yard all day, and we have a dog and kids,” the man says. “And my son is a little scared to go out in the backyard right now.”

As the main dispatcher for wildlife calls, Barrett can send an officer to the scene. What she can no longer do, in a reversal of policy since her first job here in the 1990s, is lend out traps. She also won’t follow the old practice of explaining legal methods for removing animals. But Barrett doesn’t want to do any of these things anyway. Her goal is to prevent conflict and encourage coexistence, and through inquiry and counseling, she’s able to resolve about half the concerns and complaints by the time she hangs up the phone.

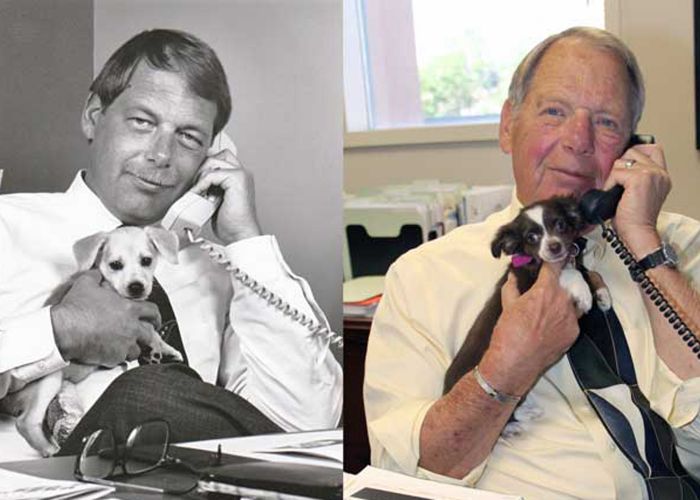

As she runs through a few questions—“Is he sitting up? Is he lying down? Oh, he’s walking around?”—her Chihuahua curls up quietly next to her desk. When Barrett adopted her three years ago, Millie was nearly bald from skin allergies. Now she’s fully furred and dressed up like a bumblebee for Halloween.

The caller interrupts Barrett’s queries: “There he goes running across our yard again! We think there’s a family of rabbits under our shed.”

Barrett reassures him. “OK, so what he’s doing is he’s hunting,” she says. “What’s going on right now sounds normal. When we get involved it’s generally because an animal really needs to be removed from the community, and it just can’t get up and run away anymore.”

Incidents involving wildlife and domestic pets are rare in Arlington, but when they occur, it’s usually because one of the animals was startled. Before going outside, Barrett advises the caller, make sure the fox is aware of your presence by banging on the door or clanging pots and pans. Prevent the fox from focusing so much of his attention on the yard, she adds, by reading the tips on WildNeighbors.org. “And if you ever have an animal that is not able to get up and run away,” Barrett concludes, “there is an officer on duty 24 hours a day for such an emergency.”

“Great, thank you so much,” the caller responds, his voice melting into relief. “Have a good one.”

Though she didn’t tell the caller, Barrett knows well the sad results of trapping and removing healthy animals from their environment. She once worked for a popular nuisance wildlife control company that claimed to be humane. She lasted four days.

“I took a call from someone who wanted all the squirrels gone from their property,” she recalls. “… And they go out there and they put a bunch of traps and peanut butter, and they trap every squirrel that they possibly could and they kill it. And it was like, well, you’re setting baited traps outside; of course you’re going to catch squirrels.” But because the company charges a fee for each animal, it’s in their financial interest to keep trapping, even though more squirrels will continue to show up, perpetuating an endless cycle that contributes to the unnecessary killing of millions of wild animals each year.

After Barrett ends the fox call, Toussaint peeks in, and they chat about some of the more unusual calls staff have received from a public prone to panic: a snake that turned out to be a shoelace, and an injured owl who was really a mushroom. Once someone called about a bat in her daughter’s room, and an officer showed up and found a scrunchie. “We want that,” Toussaint muses. “You don’t hope to find [something] horrible. You hope you get there and it’s a scrunchie!”

The oldest raccoon in Arlington

Toussaint freely admits there was a time when her own wildlife identification skills were lacking. She may have been able to tell a scrunchie from a bat, but she couldn’t distinguish one snake from the next or a baby robin from a baby blue jay.

When she became a deputy seven years ago, her 117 hours of state animal control academy training included only two hours on wildlife, she says. To bridge the gap, she’s read books, shadowed wildlife rehabilitators, taken classes and consulted with county natural resources staff. She finds trainings for her officers through rehabilitator groups and the Wildlife Center of Virginia. And for the past two years, she’s set up daylong workshops, inviting agencies across the state to learn from HSUS Wild Neighbors experts about wild animal behaviors and humane conflict resolution strategies. It’s helped address the huge discrepancy between demand for conflict mitigation services and lack of knowledge about how to fulfill it.

“Before partnering with HSUS, there was no posted continuing education for wildlife approved by the state vet’s office,” Toussaint says. She’s repeatedly taken the same classes on animal fighting, search warrant execution and cruelty investigations— all important topics, she notes, but none as sorely needed as basic knowledge about wild animals. “My officers will do more wildlife calls in their tenure here than they will do cruelty investigations— by tenfold.”

A year into his first job out of college, one of those officers, Cliff Ballena, eagerly anticipates an opportunity to shadow squirrel rehabber Barbara Prescott in her facility. He displays a photo of one of his early rescues on his desk. “It’s my first baby black squirrel,” Ballena says proudly. After a mail carrier found the squirrel covered in flies, Ballena and another officer brought him back to the shelter to bathe him before sending him to Prescott for intensive care. “This job’s definitely got me with the baby squirrels,” says Ballena. “I’m just a sucker for them.”

Before participating in the Wild Neighbors training, Ballena didn’t know that a doe will leave her fawn in a protected spot while she goes off to forage. He didn’t realize fledgling birds are usually closely watched by parents nearby. And, like so many members of the public, he thought raccoons and foxes wandering during the day were likely rabid. “I would have definitely called animal control if I saw things like that,” he says.

“My officers will do more wildlife calls in their tenure here than they will do cruelty investigations—by tenfold.”

—Jennifer Toussaint, Animal Welfare League of Arlington

Now at AWLA, Ballena relishes broadening people’s perspectives. Responding to a recent call about a “rabid” raccoon, he arrived to find “the oldest raccoon in Arlington,” he says—grayer and slower than a youngster might be, but otherwise fine. “I had the whole neighborhood coming out. … They were really scared of it and wanting me to remove it.” As residents watched the raccoon quickly amble away when Ballena approached, they realized he was not a threat. “They learned that not all wildlife needs to be picked up, and that they’re living with us just like we’re living with them.”

It’s a crucial step that many agencies too often skip, says Alonso Abugattas, Arlington County natural resources manager: “First of all, find out what it is. Is it really an issue or not? In the vast majority of cases, it’s not.” Under Toussaint’s leadership, he says, AWLA has become one of the few animal shelters that actively educate the community about natural behaviors they should expect from urban wildlife.

By helping county residents see the world from animals’ perspectives, Toussaint makes wildlife behaviors more relatable. While fox fathers are dedicated parents who help raise young, she tells people, “raccoon dad stinks. Raccoon dad does the deed and takes off, so raccoon mom’s a single mom; she’s trying so hard all by herself.” A 4-foot black rat snake in a mailbox is likely attracted to insects around the adjacent porch light, but there’s no reason to fear him: “This snake has been a member of our community for at least four years,” she tells worried homeowners, guessing his age based on his size. “Imagine how hard it is for a snake to do well in Arlington County. This snake has figured it out. … Previously he was in the basement apartment; he just put himself in the penthouse. He’s just looking for an upgrade; he’s not looking to scare you.”

Partnering to save turkeys and bats

In spite of their fears, in survey after survey, residents of Arlington County place a high value on parks and wildlife. Even apartment dwellers usually live within a couple blocks of a park, inspiring an appreciation for nature, says Abugattas. “If you are built up, and this is your one little park that’s nearby, you work hard to protect it.”

The parks department aims to “preserve what we have left,” he says, and also to bring back some of what’s been lost, most recently planting sweet crab apple, sugarcane plume grass and other species that historically provided food and shelter to animals. These efforts may be the reason animal control officers recently started receiving calls about skunks eight years after they had effectively vanished, he says. “We’re getting these animals that had disappeared from the county—species of butterflies, wild turkeys, bobcats—all of these things returning. That does mean, though, that since people aren’t familiar with this wildlife, when one turns up, people ask a question, and they go to AWLA or they come to us.”

One wild turkey caused a stir when he showed up at a construction site, clearly scared and stressed. After animal control captured the bird and consulted Abugattas, they met at a nearby park where Abugattas knew of at least a half dozen other turkey sightings. “Since turkeys are flocking birds, they like company, so we wanted to return it to where there were some already in existence,” he says. “But we didn’t want to move it too far, so we released the turkey together in this park.”

“We euthanize far fewer bats now just because the animal control officers know the questions to ask.”

—Tracy Hess, Arlington County Public Health Division

When wildlife show up closer to home—a bat in a kitchen or a raccoon fallen down a chimney—AWLA staff partner with another county agency to rescue as many as they can. “It used to be if they found a bat—euthanize it and move on, because the assumption was you needed to test it [for rabies],” says Tracy Hess, a clinical program manager for the county’s public health division. “We euthanize far fewer bats now just because the animal control officers know the questions to ask, and the nurses know the questions to ask.”

Through a protocol they developed together, the two agencies assess whether any people or pets have been exposed to a species that could transmit rabies. The collaboration has been years in the making but crystallized under Toussaint’s leadership. Recognizing the need to streamline the process—which used to include haphazard emails, phone calls and difficult-to-read paperwork—Toussaint, Hess and their teams created a shared, up-to-the-minute spreadsheet for tracking bite investigations. The results are lifesaving: In 2011, AWLA euthanized 25 bats and sent only four to wildlife rehabilitators. In 2017, the numbers effectively flipped; seven bats were euthanized, while 21 went to rehabbers. Though the public health division’s priority is to protect people, “neither of us is focused on strictly animals or strictly humans,” Hess says. “There’s tons of wildlife in Arlington, and we’re just trying to live peacefully.”

War and peace and baby blue jays

As Ed McEvoy walked the length of Arlington National Cemetery and back again, he could feel the baby blue jay’s heart beating. A Veterans Affairs specialist who served in the Marines, he’d come to this sacred spot to offer mental health services to veterans and families of fallen service members, and to visit the graves of friends in Section 60, where men and women who died in Iraq and Afghanistan are buried.

But on that warm Saturday just before Memorial Day, sounds of distress stopped McEvoy in his tracks. “I heard these loud little screeches coming from the ground, and I was like, ‘Oh, something’s hurt.’” Looking down, McEvoy saw two baby birds covered in flies. Only one was still alive. “I just picked him up, cupped him in my hand, and held him close to me.” With no nest or bird parents in sight, McEvoy decided to search for help, to no avail. Park police expressed regrets; they had standing orders not to interfere with wildlife. Officials at other agencies advised McEvoy to “let nature take its course.” Eventually McEvoy brought the bird inside an air-conditioned mobile unit to try to help him cool down.

He called “everybody and anybody,” praying for help. “I figured in an area where there is so much that’s reminiscent of death, if I could preserve a life … I had to do whatever I could.” Finally, he connected with an AWLA dispatcher, and an officer was on the scene within 15 minutes. Later, McEvoy was thrilled to receive an update that the bird was in the capable hands of a wildlife rehabilitator.

To AWLA staff and the larger community of wildlife rescuers, rehabilitators and educators, stories like McEvoy’s illustrate a fundamental principle of their work: Protecting wildlife and protecting people go hand in hand. Bat rehabilitator and educator Leslie Sturges, who’s worked closely with AWLA for years, has little time for the typical recommendation to “let nature take its course.” A rabbit run over by a lawn mower isn’t a victim of the natural ecosystem, she points out. Nor is a snake entangled in garden netting, a baby raccoon orphaned by a car, or a bat falling out of siding of a house where he roosted because it was the only habitat he could find. “What’s wrong with wanting to help that animal?” asks Sturges. “If our goal is to have a humane nation or a humane populace, then people need an outlet for their care and compassion.”

AWLA has learned how to provide that outlet by harnessing the compassion of the whole community. Dozens of volunteers work on-call to drive animals to rehabbers. A few, like Margaret Pratt, will drive wherever needed—up to two hours away late at night—to deliver opossums, squirrels, fawns, foxes, turkey vultures. Some of the animals “may not be the sort of thing we want to hold up and cuddle,” says Pratt, a toxicologist who started volunteering at the shelter by fostering kittens. “But they all have their niche in the environment.”

The human connection

A couple of hours after Toussaint rescued the injured pigeon from the road, the bird takes a turn for the worse. The AWLA team consults with a rehabber and decides to end his suffering. Later that night, though, they’ll save another bird— one of many more rescues to come. In the meantime, they’ve also got their hands full keeping up with their community’s more gregarious wild residents. There’s the snapping turtle who keeps heading back and forth across the same major intersection: “If he doesn’t cut it out … !” Toussaint says in mock exasperation. There’s Ma the fox, who suns herself on a sidewalk across from the Walgreen’s while her kits play: “That’s just Ma,” Toussaint tells alarmed callers. “She’s been doing this for six years; her den is actually nearby.” And then there’s Lucy, the deer with a limp who has twins each year and a preference for expensive plants. “We’re very sorry—Lucy has a habit of going after geraniums,” Toussaint tells people. “But she was also struck by a vehicle three years ago and still managed to raise and wean those two.” By the time the conversations are over, she jokes, people are “going out and offering their geraniums to these animals.”

Whatever the nature of the call, whether it’s an animal in distress or a person who’s afraid or simply a question from a curious person in the grocery aisle, she’ll stop to answer. If you help someone understand why he should leave a healthy fledgling bird alone, she reasons, he’s more likely to call again about a dog tied outside in freezing temperatures or a fox struggling in the road. “It happens all the time. I’ve been running calls for service too often and too much to not see this connection over and over again. Because we’re just the animal people—it makes it so easy for people. It’s too confusing to say, ‘Well, we care more about this one and less about this one.’”

For people like McEvoy, they all matter. As a former police officer, McEvoy is familiar with the challenges many shelters and animal control agencies face, and he knows that community wildlife services are still rare. But as an animal lover with two dogs and a passion for watching the wildlife in his backyard, he’d like that to change. After his encounter with AWLA at Arlington National Cemetery, he pledged to make a donation in honor of the little blue jay.

“The sincerity of everybody over the phone—and in my meeting in person with the animal control officer—you could just tell they love their jobs and they’re the right people in their positions,” he says. “There need to be a lot more places like this.”