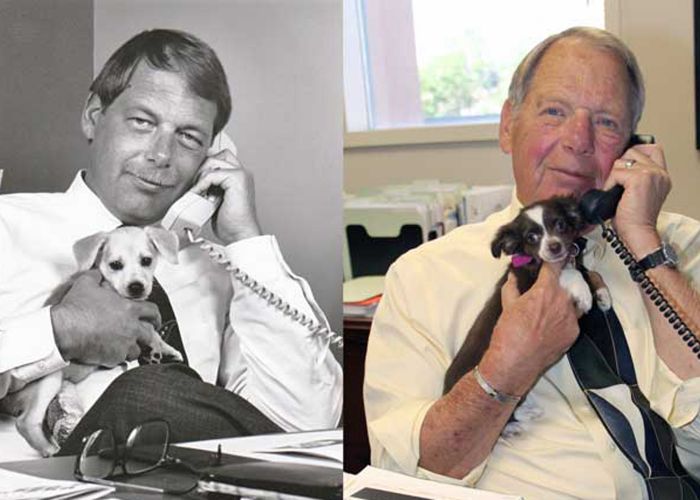

Fired up

Former shelter dogs train to sniff out suspected arsons

A stray found roaming the streets of Bloomington, Illinois, in 2009, Kai didn’t make the best first impression.

“I thought she was crazy,” says Justin Davis, an instructor for the San Antonio Fire Training Academy in Texas and K-9 handler for the city’s arson bureau. “I didn’t know what I had gotten into or how it was going to work out. She was like lightning out of her crate. She was off the walls and all over the place.”

But when Davis put Kai’s keen nose to work, he knew he had found an exuberant, willing-to-please and athletic canine who would thrive as an arson detection dog. “She’s just built to work,” says Davis, who launched the city’s accelerant dog program in 2010 when Kai came on board.

Davis and Kai are graduates of the State Farm Arson Dog Program, established with the Maine State Police in 1993. Dogs trained in the program develop noses that know arson. They sniff out minute traces of accelerants such as gasoline and lighter fluid in burned-out homes and businesses to help law enforcement investigate fires, combat fraud and bring arsonists to justice. Over the years, 390 dog and handler teams from the U.S. and Canada have been certified.

Like Kai, most recruits hail from shelters or rescue groups, or are guide dog or adaptive disability program “dropouts.” McLean County Animal Control had picked up Kai in Bloomington, which just happens to be home to State Farm’s corporate headquarters. A staffer from the Humane Society of Central Illinois noticed Kai’s obsession with ferreting a tennis ball from the bottom of a toy bin. Her drive was obvious. With a phone call to Maine Specialty Dogs, trainers for the Arson Dog Program, Kai’s working career was launched.

“Whether it’s a shelter dog or a dog that was trained to assist human beings, we just want to find the right job for these dogs,” says Heather Paul, a State Farm public affairs specialist who has coordinated the program since 2010. “We actually don’t care if the dog is hyper. We want the dog to have a strong work ethic and a lot of enthusiasm.”

Separation anxiety isn’t a problem either, because the dogs are with their human handlers all day.

The program doesn’t buy from breeders. “There are far too many amazing dogs that are languishing in animal shelters and rescues,” Paul says. “When you’ve got that many wonderful tools out there just waiting to find their right job, how can you possibly justify going to a breeder?”

Hot on the trail

At Maine Specialty Dogs, trainers take the dogs through several months of “imprinting,” in which they learn to associate the smell of accelerants with food rewards, says owner Paul Gallagher, who is also a former Maine State Police K-9 trainer. When dogs smell the “hot can,” they sit, touch their nose to the can and get a handful of dog food. After training, the dogs are paired with handlers, and together they go through a 200-hour certification class.

Arson costs big bucks. Although the number of intentionally set fires each year in the U.S. has generally trended downward in the past decade, in 2014 there were an estimated 248,500 intentional fires resulting in $839 million in property damage and an estimated 410 civilian deaths and 1,150 civilian injuries, according to the most recent figures from the National Fire Protection Association. State Farm underwrites the $25,000 cost to train each dog and handler; that figure includes travel to New Hampshire or Maine for initial training, food and lodging and other expenses.

Dogs who excel are often Labs or Lab mixes who have a strong work ethic and high prey drive and are food-motivated and friendly.

The latter is important during fire safety and arson awareness talks to school and community groups. And because some arsonists get a thrill from returning to the scene to watch the investigation, detection dogs will sometimes walk around crowds, sniffing shoes and pants—and they’ll occasionally even find the perpetrator, Paul says.

Handler-dog teams undergo a two-and-a-half-day recertification every year and are certified to standards governed by the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Most dogs are young adults when they start in the program, have a career span of five to nine years, and then live with their handler when they retire.

Even at age 11 now, Kai has two speeds, Davis says: “full blast and sleeping, and there’s not much in between.” The pair has worked more than 300 fires. They typically roll up an hour or two after the fire has been extinguished. Before he gets Kai out of the car, Davis walks the scene to identify glass, nails, “hotspots” or other potential dangers. On the job, Kai doesn’t hesitate to bound up burned-out stairs or navigate other obstacles.

“We go to some of the worst parts of town and see some of the worst things you could ever imagine, and I’ve never seen her shaken,” Davis says. “She knows I’m not going to let anything happen to her, but she’ll also go into these scenes just fearless.” Kai’s only been hurt once, but not on the job: “She was playing and bit a stick, and it jabbed her mouth,” Davis says.

Kai’s super sleuthing paid off big a few years ago at a large building that was rented as a ballroom for special events. There was fire damage near a disc jockey booth, so authorities assumed it was an accidental electrical fire. But walking down a hall on the unburned side of the building, Kai sat, put her nose to a wall and got excited. Investigators opened the wall and saw that someone had poured an accelerant into an electrical breaker box hidden behind it—an obvious attempt to fake an accidental fire.

Davis says Kai and the department’s other arson dog, Jenna, another State Farm graduate, are treated “almost like athletes” and get top-notch care. Kai lives with Davis and his family, has her own chair and a couple of dog beds. Even at home, most arson dogs never eat out of bowls but only out of a handler’s hand when being trained and rewarded. At a healthy 67 pounds, Kai is “all muscle,” Davis says.

When the pair travels, people often pet Kai and tell him they owned a former shelter or rescue dog, “and it’s the best dog I ever had.” Davis says Kai’s an example of how a shelter animal can thrive given support, love and a job. “A dog like Kai needs something to focus on or they’re going to get into trouble,” he says.

Davis says he’s seen plenty of high-dollar dogs bred for police work, and Kai is “as good if not better than every one of them.” And their bond is clearly something you can’t put a price tag on. “To me, she’s priceless,” Davis says. “She’s ruined me because I don’t ever want another dog.”