Greener pastures

Equine facility provides safe haven for abused and neglected animals

When the trailer finally pulled to a stop, the horses shuffled nervously as the rear door rolled open. One by one they exited the trailer, hooves clopping slowly down the metal ramp. The place they’d come to wasn’t home, but it was just as good—a resting place where wounds, both visible and hidden, could be healed.

It was September 2015, and 59 horses had just made the long journey from Houston to the Harmony Equine Center in Franktown, Colorado. They were part of one of the nation’s largest recorded horse cruelty cases, in which 207 horses were seized by the Houston SPCA three months earlier. The horses had been removed from a farm in Conroe, Texas, whose owners were charged with 20 counts each of misdemeanor cruelty to livestock animals for denying the horses shelter, water, food and basic care.

As for the horses who arrived at Harmony, it was up to the staff there not only to get them healthy, but also to restore their trust in humans.

Heaven for horses

Established in 2012, the Harmony Equine Center—a program of the Denver-based Dumb Friends League—has quickly established itself as one of the premier horse rehabilitation and adoption facilities in the country. Most of the animals who end up there come from dire straits; Harmony’s primary purpose is to serve as an impound, rehabilitation and adoption facility for equines (primarily horses, but occasionally donkeys and mules) seized by law enforcement. Prior to its establishment, Colorado officials had virtually nowhere to house equines seized from cruelty or neglect situations.

“This is not a new problem for law enforcement in rural Colorado counties with small populations,” says Dumb Friends League president and CEO Bob Rohde. “Their resources are limited and they want to do the right thing.” The center, he says, allows the Dumb Friends League and law enforcement to partner to help these horses.

Today, the sweeping 168-acre facility is home to three large barns for intakes, training and adoptions, roughly 50 interior box stalls, two indoor riding arenas and an education center. The property also includes a 40-acre pasture where horses can experience “free-range” life, learning how to manage wildlife encounters, water obstacles and other common issues that can be especially frightening to formerly abused or untrained horses.

Harmony has its work down to a science. Because horses who arrive there as a result of seizures are part of ongoing cases, staff must keep diligent records about their health and behavior while on-site. Any information gathered is passed to law enforcement for use in the cases. “We document everything here,” says Duane Adams, Dumb Friends League vice president of operations. He is quick to add that staff remain neutral in their observations. “Our role is to collect data,” he says, “not to build a case.” That’s up to law enforcement.

For example, a common claim among owners charged with starvation is that the horses just wouldn’t eat. Seized horses who arrive at Harmony are given free access to grass hay, which has been tested for nutritional value. If the horses eat willingly and gain weight, those observations and data on weight gain are shared with law enforcement officials, and the prosecutor may use them as evidence to support the claim that the owner was not feeding the animals.

When horses seized by law officials arrive at Harmony, they are weighed and, within 24 hours, seen by a veterinarian. The vet gives a basic exam and treats any obvious injuries. The horses are then weighed weekly and monitored for health issues.

“A lot of these cases that come in, people just aren’t feeding them,” says Garret Leonard, director of Harmony. If horses are still not improving or regressing after a week, Harmony will take additional measures. For example, a horse who isn’t eating might be found to have dental problems, such as pointed and uneven teeth or mouth sores that make eating either uncomfortable or impossible. Having a horse’s teeth examined at least annually (depending on the horse’s age and health condition) is a generally accepted guideline, so a horse’s dental condition can help to paint a picture of her overall care, or lack thereof. In those cases, a veterinarian will “float” the horse’s teeth (filing them so they are even), or the horse will be given a soft diet consisting of soaked pellets.

The court cases typically reach the disposition stage within 14 days, after which the court releases the animals to the agencies that seized them. (But some cases can take up to a year, and if owners are found not guilty, the horses are returned to them.) While some law enforcement agencies will hold their own adoption events or otherwise find homes for the horses once they gain legal custody, most agencies sign them over to Harmony.

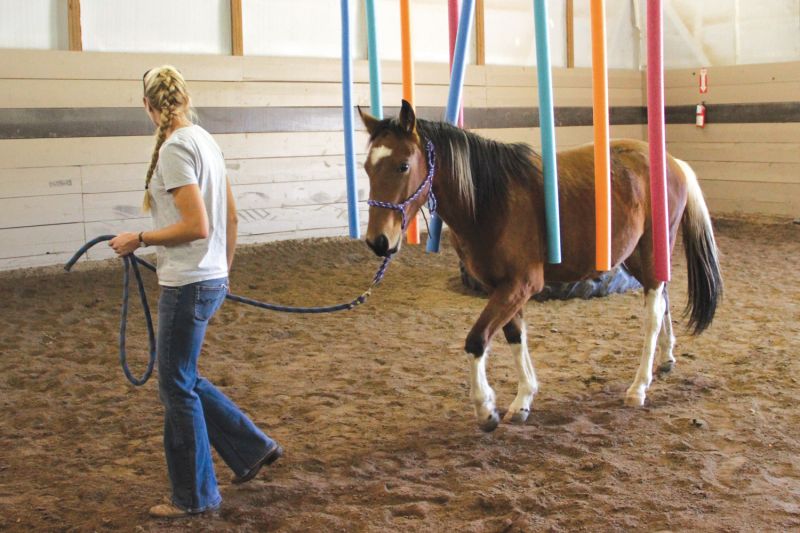

Once Harmony has official possession of the horses, the facility can provide more extensive medical care, as well as behavioral rehabilitation services. This is where Harmony’s training staff and roster of more than 90 regular volunteers come in. (Volunteers are not permitted to work with horses whose legal cases are still active.) Harmony has four full-time staff dedicated to training. Two trainers, along with Leonard, live on-site, so if there’s ever a health emergency or a heavy snow day, the horses still receive all the care and attention they need.

The horses have to learn (or relearn) to trust humans. To accomplish this, Harmony trainers work with each animal as if he were a colt and had no prior training, regardless of the animal’s actual age.

Happy trails

When Harmony opened its doors, staff expected to achieve about a 50-percent live-release rate because most of the incoming horses are in such deplorable condition, often suffering from starvation, overgrown and infected hooves, joint injuries, open wounds, mouth sores and so on, to say nothing of their emotional and behavioral issues.

But thanks to its dedicated staff and volunteers, the organization surpassed expectations; in 2016, the live-release rate was 83 percent. The average length of stay for a horse at Harmony from arrival to adoption is 168 days.

Each year, many thousands of horses transition out of working roles or find themselves in need of new owners, and a coalition called the Right Horse Initiative is addressing this challenge by working to increase the number of successful horse adoptions; the Dumb Friends League is part of that effort. In 2016, the WaterShed Animal Fund awarded Harmony a grant to expand its efforts beyond cruelty cases. Since March 2016, Harmony has taken from other shelters 180 hard-to-home horses who would benefit from Harmony’s training and adoption resources. Harmony’s ability to invest so much time and dedicated resources to each horse, giving them extensive rehabilitation and training, has given the center the reputation as an excellent resource for adopters, who come from all over Colorado—and sometimes beyond. (Harmony’s farthest adopter to date came all the way from Carmel Valley, California.)

The center takes great care in matching horses with just the right owners. After all, one horse could be great for a Western or trail rider, but hopeless for dressage or arena work. Then there are the “pasture pets”—horses whose riding days are long past, but who would still make great companions.

Would-be adopters can view available horses online, complete with photos and notes from the trainers. Adopters then meet and interact with the candidate horses (yes, very much like “The Dating Game,” but with fewer leisure suits). Once a match is made, adopters can participate in three sessions with a trainer so that horse and rider can get accustomed to one another’s personalities and quirks.

Apryl Steele, a veterinarian and Dumb Friends League chief operating officer, says that the average horse in America changes owners seven times in his lifetime, so Harmony helps adopters find the “right horse for right now.” Harmony has only a 3.6-percent return rate, with adopters’ changing financial circumstances the most common reason for return.

Over the past five years, Harmony has taken in 1,039 horses and rehomed 740. “It’s hard right now to keep adoptable horses,” says Leonard. “We can’t get them trained fast enough—even for how fast we can train them!” Much of this is due to the Harmony staff’s extensive training resources and the care they take matching horses with adopters. Adds Leonard, “We frequently have repeat adopters.”

While the horses from Texas were deemed to have been cruelly treated in the July 2015 civil seizure hearing, the previous owners filed an appeal. The trial in a higher court again determined that the 207 horses had been cruelly treated and awarded them to the Houston SPCA. In May, the owners were found guilty on animal cruelty charges.

A year after they arrived, 40 of the 59 horses who came to Harmony had been adopted. Sadly, two died, and 17 had such severe health and behavioral issues that they had to be euthanized to end their suffering.

Among the survivors was Galveston, a 5-year-old quarter horse who had major hoof problems, was emaciated and appeared to have had little or no human contact.

Enter Ellie Lemberger, a 13-year-old from Ken Caryl, Colorado, looking for a horse she could ride in Westernaires—a mounted precision drill team. Ellie’s family had adopted four dogs, so they figured, why not adopt a horse?

Head trainer Brent Winston identified several horses—including Galveston, who had been at Harmony for five months—as potential matches. In the end, the Texas gelding was the one who stole Ellie’s heart. Back home, the family hired a private trainer to continue working with Galveston, recognizing he would still need time to develop if he was to get to the level of precision arena work. Says Ginger Lemberger, Ellie’s mother, “He wants to learn and to please, and he’s so responsive.”