The hard work of building soft skills

Workplace culture agreements help animal organizations foster emotional intelligence

When COVID-19 cases began to escalate in the U.S., shelters across the country began sending animals to foster families, adjusting programs and updating protocols to keep animals, staff and the public as safe as possible. At the Pima Animal Care Center in Tucson, Arizona, staff acted quickly to shift their shelter/foster ratio from 50/50 to 10/90, housing just 120 animals in-shelter with 1,200 in foster. Volunteers, including the newly unemployed, flooded the shelter with offers to help. Veterinary programs had to be reorganized and a new system devised for adoptions that would limit social contact.

Such rapid and sweeping changes could cause massive disruptions in even the best organizations, yet according to shelter director Kristen Hassen-Auerbach, “It was seamless. We pivoted in a day, and everything was different. And it was different again two days later. It’s been kind of amazing to watch.” And it was all possible, she says, thanks to the shelter’s workplace culture.

For years, shelters and rescues have been building disaster response capabilities and devising strategies to address the evolving challenges facing animals. From more robust foster programs to enhanced partnerships among shelters, rescues and other animal protection organizations, the future of animal welfare is likely to rely even more on effective collaboration among humans. According to Katherine Shenar, executive vice president of The Association for Animal Welfare Advancement, the highest performing and most cohesive teams are fueled by a connection to the organization’s culture that includes a deep understanding and adherence to its core values, and workplace culture agreements are an effective tool for supporting this.

The future of animal welfare is likely to rely even more on effective collaboration among humans.

More than a poster

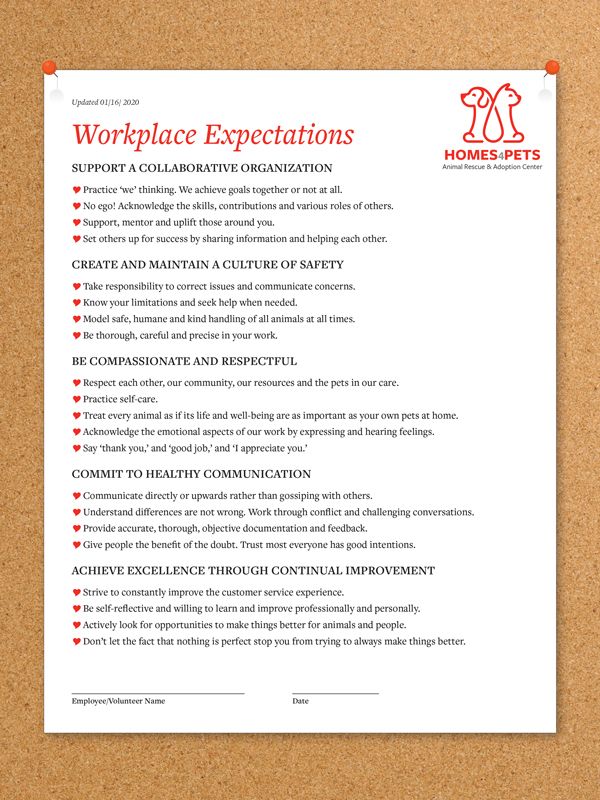

Hassen-Auerbach credits her team’s performance to this one little document with big organizational buy-in. In Pima’s workplace culture agreement, “The first two rules are ‘be kind’ and ‘be safe.’… Be kind to every person and animal you meet, and be safe in all you do. Those two words have led everything we’ve done so far with regard to COVID-19.”

A well-crafted and thoroughly executed workplace culture agreement isn’t just a document that lives in an employee handbook (though that’s one place it should appear). Shenar describes it as “an agreement between an employee, their peers and colleagues, and the organization to adhere to a code of ethics and behavioral norms, and it’s a way to bolster the culture of the organization.”

There are several keys to getting one document to do so much heavy lifting, and one of them is to integrate it into practice even before someone joins your team. Says Shenar, “When you look at hiring people, you need to look for individuals who demonstrate some of the core values.” She adds that hiring managers should make it clear to potential employees that their success will hinge on their adherence to the agreement.

Once someone is hired, the agreement should be used as a reference point. Hilary Hager, senior director of volunteer engagement at the Humane Society of the United States, says that an effective agreement is more specific than just “do this, don’t do that.” Instead, it is clear and specific in labeling behaviors. “When you don’t have a shared understanding of what appropriate behavior looks like, you’re leaving it up to an individual’s interpretation, and sometimes people don’t guess right,” she says. “When the agreement outlines the actual behaviors … such as assuming positive intent, checking for understanding, and having a face-to-face conversation instead of sending an email, it’s more useful.”

Well-written and thoroughly executed agreements can make for stronger, more positive relationships among staff and volunteers. Hager says, “The work that we do is hard on its own. To the extent that we can minimize the conflict that we have with each other, it really helps us stay focused on the animals.” Hassen-Auerbach agrees, adding that such agreements also help to create a safe space for employees, including those who are part of marginalized groups.

“When you don’t have a shared understanding of what appropriate behavior looks like, you’re leaving it up to an individual’s interpretation, and sometimes people don’t guess right.”

—Hilary Hager, The Humane Society of the United States

Queens-based Muddy Paws Rescue is a foster-based organization with foster families in New Jersey and the five boroughs of New York City. The group adopts out roughly 1,000 dogs a year, has about 400 active volunteers, and typically has between 50 and 100 dogs in foster at any given time. Last fall the organization noticed a few incidents where a volunteer “was not behaving the way we’d hope someone wearing a Muddy Paws T-shirt would act toward another person,” says events and volunteer programs manager Erika Maher. When staff took a closer look at the incidents, they realized they were mostly rooted in the volunteer losing sight of the fact that while most people have good intentions where animals are concerned, they may just not have the same information. They wondered if a workplace culture agreement could help.

Muddy Paws staff had already been working with a consultant to help create a list of core values that reflected what volunteers and clients said they liked most about the organization, summarized in words like positive, professional, welcoming, responsive and supportive. They based the agreement on these core attributes, and when they rolled it out, they were clear that it wasn’t meant to be punitive, but to help reinforce things the public already likes about the organization. Maher says volunteers were largely positive about the agreement, and for staff, having expectations outlined so clearly makes the prospect of having difficult conversations in the future much easier.

A top-down effort

“We focus a lot on building technical skills, and we’ve gotten really good at creating a skilled workforce,” Hager says. “But there’s also this piece around emotional intelligence that we don’t focus on enough.”

As Shenar points out, “People get hired for their hard skills—their intellectual ability and their training—but they get fired for their soft skills—their ability to work in teams and to collaborate.”

Some view emotional intelligence as something you either have or you don’t, yet Shenar disagrees. Soft skills can be taught, but efforts will be futile if the organization’s culture doesn’t align with what managers are telling staff, and if its leaders aren’t practicing what they preach. “It’s really hard to have any influence over your culture if you haven’t established core values and expectations for your team. … At the end of the day, the leadership team sets the tone and accountability and leads by example.”

Yet while leaders can mean well by creating a workplace culture agreement, how it’s presented and used is critical to its effectiveness. One of the best ways to make a workplace culture agreement flop is to use it as a punitive tool. “Instead of saying, ‘Hey, you were rude to someone and we don’t like that,’ point to the section on resolving conflict responsibly,” Hager says, adding that a good agreement provides a partial script for having conversations with staff or volunteers that could otherwise be difficult.

Shenar agrees, saying that great leaders coach people relative to the agreement, and that’s at least as much about praising them as correcting them. In both cases, it’s important to be caring—demonstrating those critical soft skills—and specific. When a staff member or volunteer does something not in line with the expectations outlined in the agreement, “you can sit down and say, ‘I really care about you. I’m so glad you came to work here. Your success is really important to me and the organization. I need to give you some feedback because you may not realize that something you’ve done or an action you’ve taken is threatening that.’”

Likewise, Shenar says effective praise includes details, such as, “You did a great job today when you did X, and it was really clear that Y. Keep up the great work—I’d love to see more of that in the future.” Shenar says the document can also come alive as a guideline for organization-wide recognition, such as employee-of-the-month programs.

Tying both kudos and corrections to the workplace culture agreement takes the guesswork out of success for everyone involved.

“People get hired for their hard skills ... but they get fired for their soft skills.”

—Katherine Shenar, The Association for Animal Welfare Advancement

Nuts and bolts

Creating an effective workplace culture agreement can seem like a daunting undertaking, but it doesn’t have to be, and you can start by looking at what other organizations have done.

When Hassen-Auerbach created her first agreement, she borrowed from a template initially created by Hager and (happily, says Hager) borrowed by many shelters and rescues as a starting point for their own agreements.

Shenar says efforts should start with the leadership team outlining practices that are in line with and demonstrate the organization’s core values (much like the way Muddy Paws started its agreement). Hager adds that it’s helpful for people to have something to respond to rather than huddling around a blank sheet of paper. “Frame it as a jumping-off point,” she advises, “and focus on what works for your organization and what doesn’t.” Also, leaders can use challenging situations that have already occurred to sketch out organizational ideals and desired behaviors.

From there, a critical step is getting buy-in from stakeholders throughout the organization. “I think it has to be generated by the group; otherwise it’s going to feel like a set of rules that was imposed on people,” says Hager. She adds that circulating a Word document instead of a PDF helps to make it clear that the document is a work in progress, with suggested edits and additions truly welcome. Hassen-Auerbach’s leadership team circulated its draft to key groups of staff and volunteers for feedback. It’s important to get “informal leaders” on board, Shenar adds, because others in the organization naturally look to them for behavioral cues.

Once the document is finalized, in some ways, the work has just begun. Hassen-Auerbach says it’s not effective to just email it to everyone; many won’t read it. Her team instead turned its agreement into bright, colorful posters “plastered everywhere.” When Muddy Paws leaders finalized their agreement, they emailed it to staff, fosters and volunteers and had everyone sign it. Now they include it in the onboarding process for anyone joining the organization. They also have it posted in their adoptions van and throughout the office.

When the HSUS revamped its “workplace norms,” it held a contest where employees were invited to create playful memes that illuminated one or more of the organization’s behavioral norms using photos of their pets or other animals. (Top entries were shared throughout the organization, and winners received gift cards.)

“To the extent that we can minimize the conflict that we have with each other, it really helps us stay focused on the animals.”

—Kristen Hassen-Auerbach, Pima Animal Care Center

But wait, there’s more! After the grand rollout, resist the temptation to wipe your hands and call it a day. Hager and Hassen- Auerbach agree that the best, most effective agreements are reviewed and updated periodically.

When core values are truly part of an organization’s culture, it’s apparent in everything the group does. For Hassen- Auerbach, a critical moment came when she looked out her office window and saw a staff member working to separate two dogs for feeding. It took the staff member several minutes to coax one dog through a gate, rather than just pull her through. She says, “That’s the workplace culture agreement too. … Our golden rule is ‘no ego,’ and it’s been very clear that the staff is mission-driven, thinking about the public we serve, the volunteers and the animals.”

Document