How far can fostering go?

A new vision for sheltering is trending—and being tested—around the country

Patty, a black-and-white pit bull-type mix, caught her first lucky break in 2013 when animal control officers broke into a locked car to save her from being baked alive.

She landed at the Fairfax County Animal Shelter in Virginia, where she was surrounded by people who cared about her and worked hard to find her a home.

But Patty wasn’t making it easy. “She was barrier reactive toward people and animals. She barked at everyone and everything, and she was kind of scary to walk,” says Kristen Auerbach Hassen, who was the shelter’s assistant director at the time.

The shelter team tried putting her into playgroups, but Patty was too nervous to play. When volunteers entered her kennel to take her for a walk, she nipped at their feet. Once outside, she would jump up and cling to the handler, “not with her mouth, but it was still disconcerting,” says Hassen.

Over the next several months, Patty got out of her kennel less and less. Instead of progressing to the point where she could be placed on the adoption floor, she was so stressed “her eyes were completely bloodshot,” Hassen says, “and she was trembling in the kennel.”

Then luck struck again: On the day Patty was scheduled for euthanasia, a staff member pleaded to take her home for the night to see if she would behave any differently.

“We almost said no,” says Hassen. By then, it was hard for the shelter’s leaders to fathom that Patty would ever be adoptable.

But the dog deemed a lost cause had a surprise in store. On the day she went home with the staff member, “she walked one foot off of the shelter property—one foot!” Hassen exclaims, “and turned into the laziest, most easygoing, easy-to-handle dog.”

Later that night, Patty was sleeping peacefully on a bed, surrounded by three resident dogs and the family cat. Before long, she was adopted from her foster home to a woman who read her story and wanted to give Patty a fresh start.

For Hassen, it was a revelation—the first of many experiences showing that, for many animals, the only way to get their true measure is to get them out of the shelter.

Suspecting that Patty wasn’t an aberration, the Fairfax team devised an experiment. They placed 52 medium- and large-size dogs with behavior problems in foster homes and tracked their progress. Most were young, energetic dogs—none with serious aggression toward people or other dogs, but with enough challenges to be at high risk of euthanasia.

“When we started, we said we’ll be happy if 20% get out alive,” Hassen says. Instead, once in a home, the vast majority revealed they were “just normal dogs.” In the end, 90% were deemed adoptable and found homes, most after a month or less in foster care.

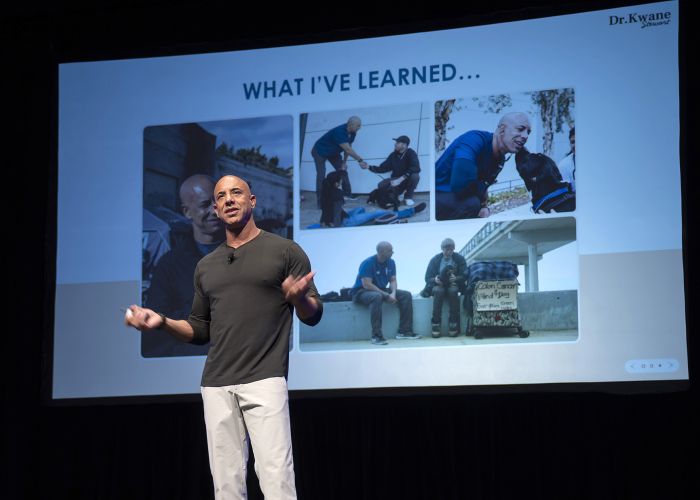

Today, as director of the Pima Animal Care Center in Arizona, Hassen presents the results of this study and subsequent research at conferences and workshops around the country, promoting foster care in all forms and for all animals. With a grant from Maddie’s Fund, she and her team at the Pima shelter are leading what they believe is the largest foster care program in the nation’s history, one that placed more than 5,000 cats and dogs in foster homes last year. In the process, they’re testing the boundaries of what foster care can achieve and what it takes to run a high-volume program.

It’s all part of a vision that Hassen shares with an increasing number of her animal welfare colleagues: In the future, the only animals who will spend significant time in a shelter will be those who need services offered in that shelter, such as specialized medical care or advanced behavioral rehabilitation. The rest will be napping on couches, cavorting in backyards or climbing cat towers in temporary homes throughout their communities. And when someone asks where the local animal shelter is, the answer will be, “all around you!”

“If you have people going onto social media and seeing foster pet after foster pet, it’s like, ‘Well, fostering is what we do ...’ It’s not scary; it becomes the norm.”

—Kelly Duer, Maddie's Fund

The home before the home

Hassen began her animal welfare career at an Ohio animal shelter in the late 1990s. “You’d walk by the kennels, and if a dog growled or gave a hard stare, you put a red E on the cage, and that dog would die at the end of the day,” she says. “No one would have thought of fostering.”

Sheltering has come a long way since then. High-volume spay/neuter clinics, trap-neuter-return, community outreach and surrender prevention programs are decreasing intakes, while kennel enrichment, doggy playgroups, communal cat rooms and other innovative programs are improving quality of life within shelters. Many shelters are able to hold animals for longer periods, and live-release rates have improved dramatically.

But there are still too many animals who can’t adjust to shelter life. For them, longer hold periods don’t translate into better chances; with every passing day in a kennel or cage, they just become less adoptable, a phenomenon that’s given rise to terms like “cage stress” and “kennel crazies” in sheltering lingo.

While foster care has become a standard part of shelters’ lifesaving strategies in recent years, for the most part, it’s been an underutilized tool, limited to underage puppies and kittens and the occasional medical case that’s best handled in a home environment, says Dr. Sheila Segurson, a veterinary behaviorist and director of research at Maddie’s Fund.

To change this, Maddie’s has developed resources and trainings that empower shelters to take foster care to a new level—one that encompasses animals of all ages and with a range of needs. It’s something that Segurson, who has been fostering shelter dogs for nearly two decades, feels passionate about. Foster care isn’t just about increasing live-release rates, she says; it’s also about improving the welfare of animals while they await adoption. “I want to see a world where we no longer have these dogs who have been in a shelter for six months; they came into the shelter as a friendly, outgoing dog with no obvious problems and deteriorate over time,” she says.

Through Maddie’s apprenticeship program, shelter and rescue group staffers are getting hands-on experience in managing large-scale foster care programs, while researchers are measuring the impact of different types of foster arrangements—from afternoon field trips of a few hours to weekend sleepovers to fostering that lasts a week or more—and studying what motivates people to volunteer in this way.

One common belief that has prevented programs from reaching their full potential is that “there are only so many people who want to foster,” says Kelly Duer, a foster care specialist at Maddie’s Fund and former volunteer at the Fairfax shelter.

Duer remembers a recent conversation with the foster coordinator at a large shelter who bemoaned the fact that only 30 people applied to serve as foster homes the previous year. Duer checked the organization’s Facebook page: “They mentioned fostering zero times. … The organizations with the biggest foster programs, they’re talking about foster as much as they’re talking about adoption, which makes sense because some animals can’t even make it to adoption unless they get into a foster home.”

Shelters are also finding that field trips, sleepovers and other short-term foster opportunities are a gateway to both adoptions and the recruitment of long-term foster volunteers—something that Duer saw play out years ago when she started volunteering at the Fairfax shelter. “My husband was like, ‘We couldn’t foster full time, we don’t have the time,’ the excuses everyone thinks.” But when the shelter began offering volunteers the chance to take dogs home for a weekend, Duer and her husband were quick to sign up.

“They had all been really long-stay dogs, and they all got adopted within a week because of the information we got,” she says. Buoyed by these results and the realization that they could fit some extra animals into their schedules, they started taking in long-term fosters.

When it comes to promoting foster care, success breeds success, Duer says, and can even lead to a shift in the culture of the community over time. “If you have people going onto social media and seeing foster pet after foster pet, it’s like, ‘Well, fostering is what we do in Indianapolis.’ It’s something people do. It’s not scary; it becomes the norm.”

Did you know? Field trips, sleepovers and other short-term foster options can be a gateway to both adoptions and the recruitment of long-term foster volunteers.

Foster and prosper

Of course, recruiting volunteers is just one of the challenges of a high-volume foster care program. For organizations that can’t afford to hire more staff, the prospect of managing a large number of volunteers and shelter animals outside the shelter’s walls can be daunting.

A solid foster care program starts with “a good foster manual, a good foster onboarding process and a foster agreement—the boring key stuff,” Hassen says. But volunteers need ongoing support, and that inevitably leads to the question: Who’s going to answer the midnight calls about the foster dog who’s vomiting or the foster cat who didn’t touch her dinner?

It’s a real challenge, says Kristi Brooks, director of operations for the Cat Adoption Team, a limited-admission cat shelter in Sherwood, Oregon. When Brooks started volunteering with CAT in 2002, there was no official foster coordinator and few defined processes. “The first year, I fostered five litters of kittens,” she says. “I felt like I was on an island. I’m playing with kittens until I’m not and things go wrong.”

A year later, Brooks took on the role of volunteer foster coordinator and was quickly confronted with the herculean task of providing the support she’d craved as a caregiver. “Everyone was calling me 24/7,” she says.

Over time, she developed a structure that CAT now teaches to other animal welfare professionals through Maddie’s apprenticeship program. Under the CAT model, experienced foster caregivers serve as mentors to other fosters in their area. These highly committed volunteers not only take calls and answer questions, but also, following veterinary protocols, give distemper vaccines and provide hands-on help with medications. Fosters receive bags filled with items for treating common problems like diarrhea or crusty eyes, saving everyone time ferrying supplies around. In medical emergencies, mentors can consult with an on-call lead mentor to determine if emergency veterinary care is warranted.

“If things aren’t going well, everyone has someone to call,” says Brooks. The mentor model “saves us a ton of money in ER visits,” she adds, and it enabled the shelter to expand its foster care capacity from 200 cats and kittens a year in 2002 to about 1,000 today.

5,080 pets placed in Pima Animal Care Center foster homes in 2018

Another lesson the CAT team shares with apprentices is the importance of volunteer satisfaction. Retaining volunteers is just as important as recruiting new ones, says Brooks, who often hears from other organizations that they’re “getting lots of fosters, but not hanging on to them.”

What Brooks and her team have learned is that shelters can ask a lot of their foster volunteers if they treat them like valued partners in lifesaving work.

Each year, CAT hosts several workshops for volunteers on topics like feline socialization techniques, neonatal kitten care, ringworm treatment and dental disease in cats, as well as meditation and stress management. The workshops keep fosters engaged with the shelter even when they’re not fostering, and build a more knowledgeable and resilient volunteer corps, Brooks says.

Shelter staff also hold quarterly brunch meetings with the mentor group and an annual summit with all fosters, where they solicit feedback on how the organization can make their jobs easier. At the end of the year, volunteers receive what many have described to Brooks as the most meaningful thank you they have ever received: a handwritten card with the names of every cat and kitten they fostered that year.

“We have foster homes who have been with us as long as I have,” Brooks says. “You’re not on that island anymore.”

The shelter all around you

Now in the second year of its high-volume foster care project, the Pima Animal Care Center has embraced its role as a proving ground for different foster care models and strategies. “We didn’t want to just do the program,” Hassen says, “we wanted to figure out what works.”

At the same time, she adds, the project originated from a real need at the municipal shelter. In a county of just over a million people, Pima takes in about 17,000 animals a year, giving it one of the highest per capita intakes in the nation. On Hassen’s first day on the job, the shelter had about 650 dogs and 500 cats and kittens onsite. “It was too many animals to have in one place,” she says. “It was just madness.”

The shelter was placing about 1,500 animals a year in foster homes at the time—“a perfectly respectable number,” she says, “but it was mostly puppies, kittens and pets recovering from illness or injury.” Meanwhile, there were animals who had lived at the shelter for many months.

Since the project launched, Pima’s live-release rate has increased from 85% to 90% while the average length of stay for dogs has decreased to 12 days. The impact on the animals who remain in the shelter has been equally striking. “The shelter was so full before that animals who needed more support just didn’t get it,” Hassen says. Now with more than 5,000 animals—nearly a third of the shelter’s annual intake—in foster homes, staff are able to run playgroups and kennel enrichment activities every day.

While tackling their own fostering needs, Pima staff continue to experiment, collect data and innovate. They test and refine their processes and share their experiences with other organizations.

Among the insights they’ve gained so far is the importance of talking about foster care, loudly and often. “As soon as we started messaging, the community started coming out of the woodwork,” Hassen says. Six months after the project launched, about half of all people who walked into the shelter asked about fostering.

From her experience at the Fairfax shelter, Hassen already knew that most behavioral cases can be safely handled in foster care, and doing so doesn’t result in increased dog bites in the community. What she didn’t know was that even animals with contagious illnesses can be safely placed in foster homes.

One day during her first year at Pima, she visited the room where dogs with distemper are housed. “We were isolating them, and they were slipping through the cracks,” she says. She realized one dog had been in the distemper ward for seven months, and “that was the day we started pleading distemper to foster homes.” With the shelter closely monitoring the animals’ health and providing instructions to caregivers to prevent the dogs from coming into contact with unvaccinated animals, the distemper ward was soon empty.

“It was a lesson for me in how foster is very adaptable to different emergencies,” she says. And that “the greater the need, the more people want to help.”

Her experiences at Pima have also reinforced her belief that shelters need to make it easier for people to foster by removing barriers like lengthy training requirements or wait periods, and that they can make foster care management easier on themselves by using technology, streamlining their processes and empowering volunteers to do more.

Some of the time-savers Pima has implemented include use of the Maddie’s free mobile pet assistant app, which provides guidance to foster parents on common pet dilemmas; online training for foster volunteers; and a computer system that enables foster parents to schedule medical appointments for their animals at the shelter’s clinic. Inspired by the ASPCA’s Animal Ambassadors program, Pima encourages fosters to market their animals and to handle the adoption process, a practice that also results in speedier adoptions and frees up foster space for more animals. “Most of our foster pets never come back except for medical appointments and spay/neuter,” Hassen says.

There are still plenty of unanswered questions surrounding high-volume foster care programs. “We are truly managing an entire shelter out in the community,” Hassen says. “There are challenges with that.”

But Pima staff are regularly piloting new strategies. They’re asking questions like “How do you find fosters for perfectly average 7-year-old cats who have sat in the shelter for a year?” and looking for answers.

And thanks in part to Maddie’s apprenticeship program and research initiatives, other shelters are asking similar questions. Over the past year, Detroit Animal Care and Control, the Animal Care Centers of NYC and dozens of other organizations have launched field trips, sleepovers and other innovative foster programs. Duer calls the results nothing short of “mind-blowing.”

“They’re clearing their shelters,” she says. “... There are lines outside of shelters for people to foster dogs.”

The field is changing so fast, Duer adds, and still “we haven’t even begun to harness the power of foster care.”

“Most of our foster pets never come back except for medical appointments and spay/neuter.”

—Kristen Auerbach Hassen