A future for felines with FIP

New developments offer cheaper, more accessible treatments for feline infectious peritonitis

From the time Heather Schrader adopted Barnabus as a kitten, he’d been healthy, playful and a voracious eater. But just shy of his third birthday, the sleek black shorthair with one golden eye started losing weight and his appetite.

After exams and tests ruled out the most common ailments, Schrader received crushing news: Barnabus had feline infectious peritonitis, a disease that kills kittens and young cats within days or weeks if not treated immediately.

In April 2022, when Barnabus was diagnosed, the only known cure was an illegal drug that was smuggled into the U.S. and sold in unmarked vials. The treatment involved 84 days of injections, then 84 days of observation, taking on faith that the liquid in the vials was genuine.

Schrader, a veterinary technician in Davis, California, and student outreach program manager for the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Alliance, had heard about desperate cat parents who spent thousands of dollars on a black-market drug in an effort to save their cats. She never imagined that she would become one of them.

“If you’d asked me up until that point if I’d ever consider injecting something into my cat that was a mystery liquid, I would have said no way,” she says. “But when I was given the diagnosis that he was definitely going to die if I didn’t do it, then it was a no-brainer to me.”

In the U.S., 2024 brought two significant milestones in FIP treatment. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced that it wouldn’t pursue enforcement action on the use of compounded GS-441524 for animals, and a pharmacy in New Jersey began selling the compounded drug in a tuna-flavored tablet.

A medical mystery

Despite its name, feline infectious peritonitis isn’t infectious, but rather a mutation of the highly contagious feline enteric coronavirus, a gastrointestinal bug that is prevalent in 30% to 90% of cats worldwide.

Feline coronavirus itself is fairly innocuous. Most exposed felines show no or very mild symptoms, such as diarrhea, sneezing or runny eyes, and quickly develop immunity. Some studies estimate that only about 1% to 5% of infected cats go on to develop FIP, although others estimate the rate as high as 10%.

Why the virus mutates in those cats is unknown. “We’ve been studying it for almost 60 years, but it’s still a mystery,” says veterinarian Samantha Evans, a clinical pathologist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins.

Experts believe that the genetic makeup of individual cats is a factor in the mutation as well as each cat’s particular immune response. “It definitely has a genetic component,” Evans says. “We see it in certain breeds…and we see it in litters. …[But] there’s not a single gene that anyone has been able to discover that’s associated.”

Once the mutated FIP virus escapes the gastrointestinal tract, it spreads through the body, attacking organs and causing overwhelming inflammation. For cats with the effusive, or “wet,” form of FIP, fluid accumulates in the chest and abdomen, making breathing difficult. The noneffusive, or “dry,” form affects cats’ nervous systems, leading to neurological problems that can cause seizures, difficulty walking and serious eye problems.

Early symptoms in both types are loss of appetite, weight loss, lethargy and fever, which can be mistaken for many other ailments. The yellow color of aspirated abdominal fluid points toward wet FIP, but aside from that there’s no conclusive test for the disease and no effective vaccine to protect against it. By the time a diagnosis of FIP is made, the cat is often in critical condition. Time is of the essence.

But until 2017, time didn’t matter. There was no treatment, and few cats survived.

The road to GS-441524

In 2017, veterinarian Niels Pedersen, who had been studying FIP for decades, made a breakthrough. He and his team of researchers at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine conducted a successful trial treating sick cats with an antiviral drug called GS-441524.

Finally, there was hope, a medication that effectively reversed the course of FIP for 80% of cats. Yet Gilead, the manufacturer and patent holder of the drug, refused to submit it to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval for use in cats. Veterinarians couldn’t prescribe it. Cats continued to die.

In early 2019, Robin Kintz of upstate New York received heartbreaking FIP diagnoses for both of her 5-month-old adopted kittens, Henry and Fiona. Her veterinarian told her there was nothing to be done. Kintz wasn’t ready to accept that.

Diving into the internet, she learned about Pedersen and his work with GS-441524. She also learned that the medication was legal in a few other countries, was being produced in China and was sold in the U.S on a black market.

“I started trying to figure out how to get my hands on it short of flying to China,” she says. She came across a few Facebook groups that were discussing FIP but were staunchly opposed to black-market medications. Things weren’t looking good.

Then two women from one of the Facebook groups reached out to her privately. “They had figured out how to bring the drugs in, they were treating their cats and the cats were getting better,” says Kintz.

They helped get the first vials of GS-441524 for her kittens. Following the protocol of 84 days of injections, both cats recovered. Henry lived for another year, before dying of FIP-related complications, but Fiona is now 6 years old.

The two women also helped Kintz found FIP Warriors (now FIP Warriors 5.0), a volunteer-based group of pet parents whose cats have had FIP. Their goal was to support people looking to take a chance with this treatment to save their cats, Kintz says. Since GS-441524 could only be obtained through the black market, the group developed protocols for vetting manufacturers and having their products tested in a laboratory.

Cat parents usually find the group through an internet search or a referral from a veterinarian. FIP Warriors matches the parent and pet with a team of administrators, moderators and sometimes a volunteer veterinarian. (During treatment, the cats see their regular veterinarian for periodic bloodwork, examinations and any supplemental medication that might be needed.) FIP Warriors assists in obtaining the medication, coaching the owner through treatment and providing much needed emotional support.

“We have a treatment support Facebook group for people who have just started treatment and want to just ask other parents about their experiences, parent to parent,” says Kintz.

After she turned to FIP Warriors for help saving Barnabus’ life, Schrader received a list of GS-441524 manufacturers the group trusted. Because of his weight and age, Barnabus needed a high concentration and dosage of the drug. Schrader was looking at spending $5,500 on the drugs alone, none of it covered by her pet insurance.

She took the plunge, and within a few days of starting treatment, Barnabus had dramatically improved.

That, and the encouragement she received through the FIP Warriors forum, kept her going through the difficult months that followed. Barnabus objected to the daily injections and the sting of the acidic liquid, and he started hiding from Schrader. Her veterinarian prescribed anti-anxiety medications, and a feline behavior expert provided strategies for reducing his stress.

Schrader and her cat managed to get through the full treatment cycle, and Barnabus made a full recovery. “My bond with him is even stronger after his treatment,” she says, “and at the risk of sounding anthropomorphic, I think he realizes that it was worth the trauma, as well.”

The remdesivir alternative

At the time Barnabus fell ill, there was another, legal drug available—remdesivir (brand name Veklury), also developed by Gilead and approved by the FDA for treatment of COVID-19 in October 2020. A near twin of GS-441524, remdesivir is given intravenously and is equally effective for FIP. Because it has FDA approval for humans, veterinarians can legally prescribe it off-label for use in cats.

The hitch—it’s far more expensive than GS-441524 and only available in hospital pharmacies. A prescribing veterinarian must find a hospital pharmacy that carries it and is willing to share it for an animal. But many veterinarians aren’t aware of it as an FIP treatment.

Dr. Amanda Reading, a veterinarian in Vancouver, Washington, faced this dilemma when she diagnosed Tyrian, a 1-year-old orange tabby, with FIP in late 2023. She immediately directed his parent to FIP Warriors. Tyrian began receiving GS-441524 injections but didn’t respond, something that doesn’t happen very often, says Reading.

Combing through studies on the internet, Reading found one that mentioned remdesivir as an alternative for cats who are resistant to GS-441524. “When it became clear that I was allowed to use remdesivir, that it wasn’t just reserved for human use anymore, then it just became a matter of trying to get it,” she says.

“He got better faster than any other patient I’ve seen. He still had to do the full course of [GS-441524] treatment, but his bloodwork was normal from that point on.”

—Dr. Amanda Reading

The cost of keeping Tyrian on remdesivir for all 84 days was prohibitive. Combined with the cost of hospitalization, Reading estimates it would have been about $30,000. “The idea was to give him remdesivir for as long as we could, which ended up being days…at high enough levels to try to reduce the circulating viral load,” says Reading. “Then…the client could try a new vial of the unlicensed medication in case [the one she had] wasn’t working.”

Reading started burning up the telephone wires, calling pharmacies and a veterinary drug distributor, before she discovered that she could only get the medication from a human hospital. By chance, a friend of a friend was a pharmacist at a local hospital. Reading was able to get two vials of remdesivir, enough for a few days of IV infusions.

The plan worked. “He got better faster than any other patient I’ve seen,” says Reading. “He still had to do the full course of [GS-441524] treatment, but his bloodwork was normal from that point on.”

A new treatment option

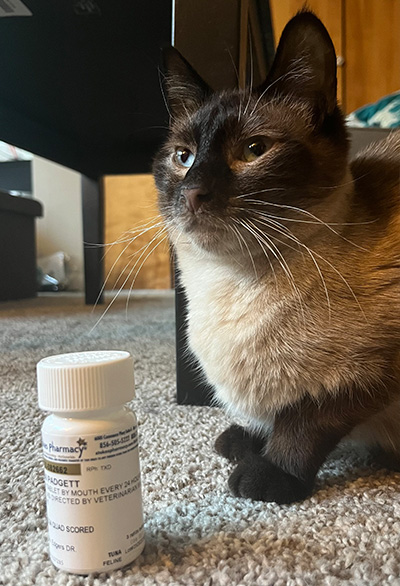

In the U.S., another important breakthrough in FIP treatment came in June 2024. Stokes, a compounding pharmacy in New Jersey, began manufacturing and selling compounded GS-441524 in a tuna-flavored tablet form.

The pharmacy partnered with Bova, a manufacturer in the Netherlands where GS-441524 is legal. Bova supplied its formula to Stokes and analyzed the product in its own laboratories, providing an assurance of purity and quality control in comparison to the unknowns of the black-market products.

The Stokes compounded product hasn’t been evaluated or approved by the FDA. Earlier this year, the agency issued a statement reminding pharmacies, veterinarians and pet owners that “animal drugs compounded from bulk drug substances are unapproved drugs and are not, in fact, legal.”

But—and this is a big “but”—the FDA also stated that it “does not intend to take any enforcement action for compounded products for use in animals.” Such products fall under an exception clause (FDA Guidance for Industry #256) that allows patient-specific prescription of medications compounded from bulk substances when there is no alternative treatment for the animal’s condition.

Veterinarians can now directly treat their FIP patients without putting their license at risk—a significant milestone in the search for an accessible and more affordable treatment option.

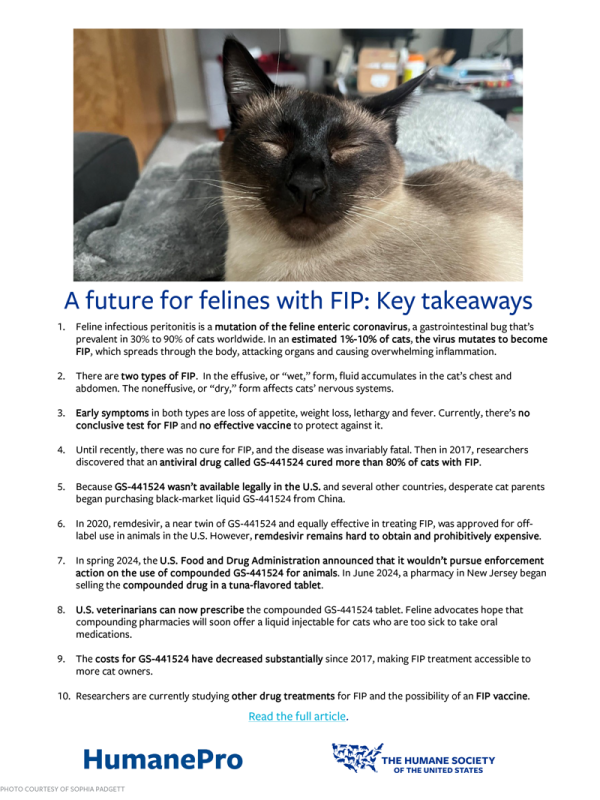

The Stokes pill came on the market just in time for Orion, a fluffy seal-point Siamese and companion to Sophia Padgett of Bellingham, Washington. In May 2024, after diagnosing Orion with FIP, his veterinarian wrote the prescription for the GS-441524 tablets.

The turnaround was remarkable. “Within two days he was waiting for me at the door for breakfast, which he hadn’t done for weeks,” says Padgett.

Hope for the future

With all its undeniable challenges, the future for FIP treatment is much rosier than it was a decade ago.

“The fact that we can treat this disease is astounding,” says Evans. “When I graduated in 2015, there was no mention of therapy. There was no hope. Now we are curing 90% of them.”

Kansas State University and Anivive Lifesciences, a veterinary pharmaceutical company, partnered in 2018 to develop GC-376, a protease-inhibiting antiviral effective against FIP, and hope to bring it to market in a year or two. Meanwhile, a research team at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine is studying the possibility of developing an FIP vaccine using messenger RNA, the vehicle used in vaccines against COVID-19.

GS-441524 prices have decreased substantially in the past two years, Kintz says, and are expected to continue to fall.

But the need to navigate the black market is still a reality for many pet parents. Remdesivir remains expensive and hard to get. Some cats are too ill to eat or take oral medication such as the Stokes tablet and must be injected until they’re stable enough to transition to oral treatment. And there are still many countries where GS isn’t legal.

FIP Warriors’ Kintz looks forward to the day when the GS black market is a thing of the past, when pharmacies will produce compounded injectables as well as tablets, and cat parents can rely on their own veterinarians for the necessary drugs. She hopes that one day her group will serve solely as a venue where pet parents can receive ongoing encouragement and tips to help them get through the challenges of treating their cat for FIP.

Until then, feline advocates, pet parents and researchers continue their fight to save as many cats as possible.

Document