Shaking off stigmas

Are you still clinging to shelter and rescue myths rather than facts?

Perhaps you “know” that black dogs are less adoptable. Maybe you think the world would be a better place if everyone were required to fix their pets. It’s logical and no one can tell you otherwise—you’ve seen the evidence with your own eyes.

No need to check your eyesight, but you might be missing the big picture. Don’t let the “backfire effect”—a scientifically proven phenomenon where people become even more set in their beliefs when exposed to the facts—hold you and your organization back from helping people and animals.

Interestingly, it’s also been proven that when people feel good about themselves, they’re more likely to accept information. So: You’re doing great work at your organization. And you look stunning today.

Now hold on to your glasses—here are the facts.

Fact: All demographics are open to spay/neuter.

The national spay/neuter average is roughly 88 percent, but in some communities, that number is as low as 9 percent—and it can be tempting to draw conclusions about the people in those communities.

Such communities typically have high poverty rates and low availability of pet wellness services. In certain parts of the country, they might also have high populations of non-English speakers. Historically ignored by many service providers (including those in the animal welfare world), and some facing a language barrier, many people in underserved communities don’t have the resources to fix their pets or simply don’t know the benefits of spay/neuter.

Alana Yañez manages the HSUS Pets for Life (PFL) team in Los Angeles, where over 95 percent of her clients are Latino. She calls the longtime stereotype that Latino men won’t neuter male pets because of misplaced machismo “absolutely not true.” Yañez has encountered men who conflate their dogs’ manhood with their own—but she definitely hasn’t found the reasoning to be culture-specific.

Yañez’s bilingual team provides spay/neuter and medical vouchers to residents in their largely Latino focus area. In 2015, they completed the most spay/neuter surgeries out of all four PFL cities—3,477 surgeries. Those who believe the stereotype “don’t work in low-income communities,” says Yañez.

Yes, some people just don’t want to fix their pets—for myriad reasons that vary from “puppies and kittens are cute” to “I don’t want to unman my dog”—but these people aren’t “specific or unique to underserved communities,” says Amanda Arrington, director of the PFL program.

Since 2010, PFL teams have had conversations with 62,000 pet owners in underserved communities across the country. Although 87 percent of pets in these communities were unaltered, through the PFL approach, they were able to increase the overall percentage of sterilized pets to be on par with the national average.

“You’re going to find a segment of people who have issues with spay/neuter in every single community,” Arrington says, but “we know that once people are engaged consistently and engaged positively and the barriers are removed—whether that’s a financial barrier, whether it’s a geographic barrier, whether it’s transportation—that if we focus on identifying what the challenges are and focus on a solution, people spay/neuter. Readily.”

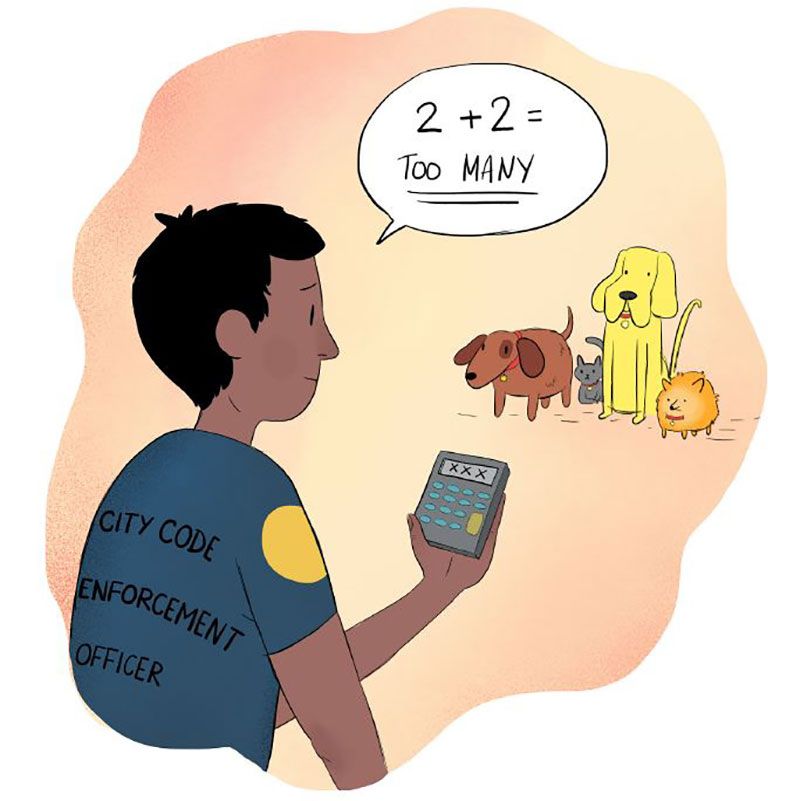

Fact: Mandatory spay/neuter and pet limit laws do not help animals.

If you’re handling the effects of unfixed pets day in and day out, a mandatory spay/neuter law might seem like a lifesaver.

“I get it. I thought that was the answer too,” says Cory Smith, HSUS director of companion animal public policy, who previously worked as an animal control officer in Washington, D.C. “When you’re working in the trenches, and all you’re seeing is the bad stuff, of course you’re looking for solutions.”

Unfortunately, if a law requires spay/neuter, but the government isn’t willing to pay for transport and surgery for people who can’t otherwise afford it, then the law essentially creates an unfunded mandate that punishes people for their income status—potentially leading to a decrease in pet licenses (like in Montgomery County, Maryland, 1997) and an increase in shelter surrenders (like in Los Angeles County, 2008) likely due to fear of criminal citations or cost concerns.

If people surrendering animals they can’t afford to sterilize doesn’t sound so bad to you, bear in mind that 23 million pets live in homes below the poverty line. Very few of those pets are fixed. If everyone living in poverty turned in their pets, shelter intake would triple. Although spay/neuter is an important tool for reducing euthanasia, keeping pets in their homes is another.

“There’s not an ideological battle over spay/neuter,” says Smith. “We know that if we make it easy and accessible for people, we will achieve the same goal, without the casualty of animals losing their homes.”

We know that if we make spay/neuter easy and accessible for people, we will achieve the same goal, without the casualty of animals losing their homes.

—Cory Smith, companion animal public policy director, The HSUS

Los Angeles implemented a mandatory spay/neuter law in 2008. Until this year, LA’s free spay/neuter vouchers were only available to those who could prove they lived below the poverty line. Proof included identifiers like address, income-related statements and a photo ID, meaning the vouchers weren’t available to homeless people or undocumented immigrants (residents may now receive a voucher after signing an affidavit indicating they can’t provide the documents).

While the mandatory spay/neuter law is being enforced, nonprofits funded by the Found Animals Foundation are simultaneously pouring money into surrender intervention programs, says Smith. According to data presented by the foundation, the top surrender prevention cost is spay/

neuter surgeries.

“These are animals who have homes,” says Smith. “We could get people to spay and neuter their animals by just reaching out … but instead, people are actively surrendering animals because they’re out of compliance with this law, and the only reason their animals are going home with them is because the nonprofit system provides a safety net.”

When a mandatory, breed-specific spay/neuter law was implemented in San Francisco in 2005, the San Francisco Chronicle’s SFGate website touted it as a success. According to San Francisco Animal Care and Control, roughly 500 pit bull-types were spayed or neutered within two years, and by 2013, euthanasia of the dogs decreased by 29 percent.

But, once again, laws don’t work in a vacuum: Enforcement approaches, community demographics and available resources play a key role. Animal control officers issue most people with unfixed dogs a “fix it” ticket and a spay/neuter voucher, not a citation.

San Francisco also happens to have one of lowest poverty rates in the country—not to mention some of the best low-cost spay/neuter programs, including San Francisco SPCA’s (SFSPCA) free pit bull-type spay/neuter program, introduced in 2008, and Peninsula Humane Society’s free, mobile spay/neuter clinic that meets people in their communities.

Staffers from SFSPCA’s Community Cares program, introduced in 2010, additionally seek out and have conversations with people in communities with high shelter intake rates, coordinating free vaccines and spay/neuter surgeries.

“If there’s going to be a mandated ordinance, then people have to have a way to fulfill it,” says SFSPCA co-president Jennifer Scarlett.

Other cities, citing public nuisance and welfare of both humans and animals, have attempted to regulate pet ownership by implementing varying pet limit laws, sometimes based on weight, age (to account for litters) or size of home.

In Baltimore County, Maryland, those with more than three dogs must obtain a kennel license. Smith recently received a call about a woman who, over time, had adopted four dogs from the county animal shelter, only to have the county require her to give up one dog.

Over the years, there have been countless examples of ordinary pet owners and fosters being affected by such laws—from a woman in Marion, South Dakota, who was asked to give up one of her three licensed dogs in a case that went all the way to the state Supreme Court, to Sauk Rapids, Minnesota, where two women, one who fostered dogs, challenged a two-dog ordinance and won.

Pet limit laws are often used as a shortcut—an easy fix for public nuisance complaints, a hoarding situation or a puppy mill—but there is no shortcut, says Smith. The fix lies in consistent enforcement of solid but basic laws addressing cruelty, neglect and minimum standards of care, not one-size-fits-all laws that provide no community support, do little to remedy true animal cruelty or neglect, can make pet owners fearful of reaching out for needed services and can cause collateral damage to loving owners and pets alike.

To Smith, pet limit laws are “arbitrary on their most basic premise, because there is no magic number of animals that guarantees humane conditions”—or guarantees conscientious owners who don’t let their pets become a public nuisance.

“We have these exceptions that are driving policy, and it ends up being used against people who have done nothing wrong and very rarely turns into a useful tool to address a real problem,” says Smith. Such laws, she adds, also take time and money away from more effective animal services.

Fact: Your community doesn’t necessarily know who you are and what you do. (Or, even if you build it, they might not come.)

You’re ready and waiting to support pet owners and adopt out animals, so if people aren’t reaching out for help or adopting, they just don’t want to, right?

Maybe people just don’t have a clear understanding of your mission and services—many people are uncertain about shelter pets or hugely underestimate the pet overpopulation problem—or maybe people don’t realize you exist at all.

“We’ve done adoption events where people have been like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know this shelter existed, this is really great,’” says Jessica Vaccaro, adoption manager at the Animal Care Centers of NYC (ACC NYC).

Raising awareness about your organization and the animals in your care can have a trickle-down effect in your community. According to HSUS research, those who have adopted a stray or shelter animal in the past are more likely to fix their pets. This highlights the importance of continuously tying the personal choice to spay/neuter or adopt—saving lives—to pet homelessness and euthanasia in shelter and rescue messaging, even if it feels redundant.

“You can talk to the most aware, educated, informed person and they still think all animals are at the shelter because there’s something wrong with them. Or they don’t know the variety of pets available for adoption,” says Arrington. “It’s a big world out there, and there’s a lot of information that people have to sift through.”

You can talk to the most aware, educated, informed person and they still think all animals are at the shelter because there’s something wrong with them. Or they don’t know the variety of pets available for adoption.

—Amanda Arrington, Pets for Life director, The HSUS

In underserved communities, where over 80 percent of people have never contacted their local shelter or animal services agency, the hesitation to reach out or adopt can even be fear-based, says Arrington.

“There’s just a lot of distrust,” she says. “One of the most common misconceptions [is that shelters are] a place where you get in trouble or where they want to take your dog or cat. … Sometimes it has nothing to do with animal welfare and it’s just an individual’s or a community’s experience with law enforcement … that then overflows into what they might think an animal shelter is.”

“We’re working really hard with our communications team to get our message out there,” says Vaccaro, but ACC NYC additionally has both a community outreach program that targets underserved neighborhoods and mobile adoption trucks that travel throughout the city’s five boroughs.

“People can come by who aren’t familiar with the shelter or who didn’t want to trek all the way up to the shelter,” she says. “I don’t think there’s ever enough outreach out there. There’s always somebody that you can reach.”

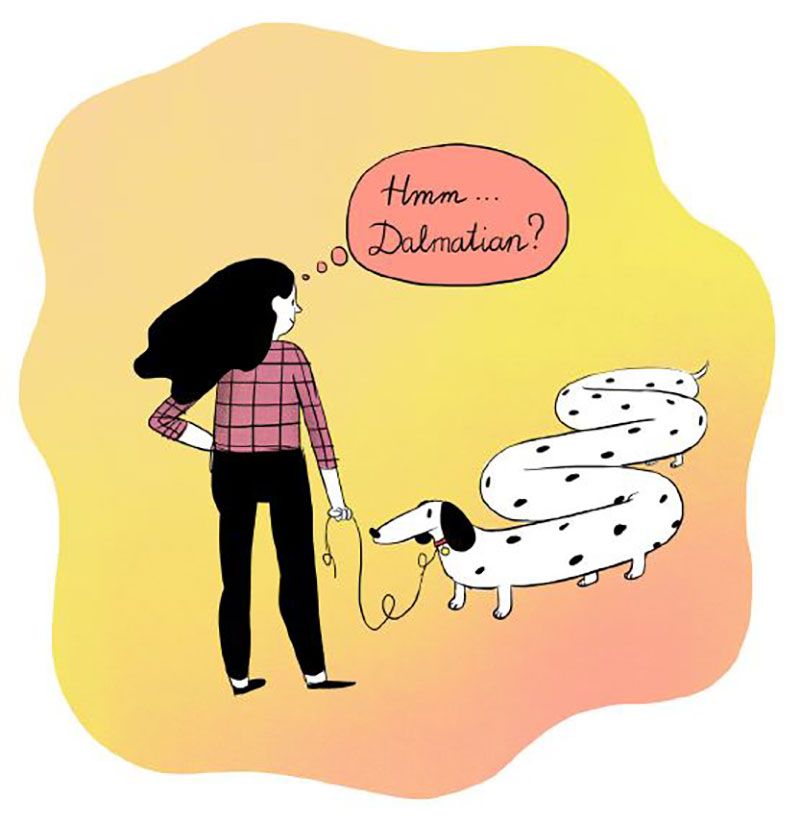

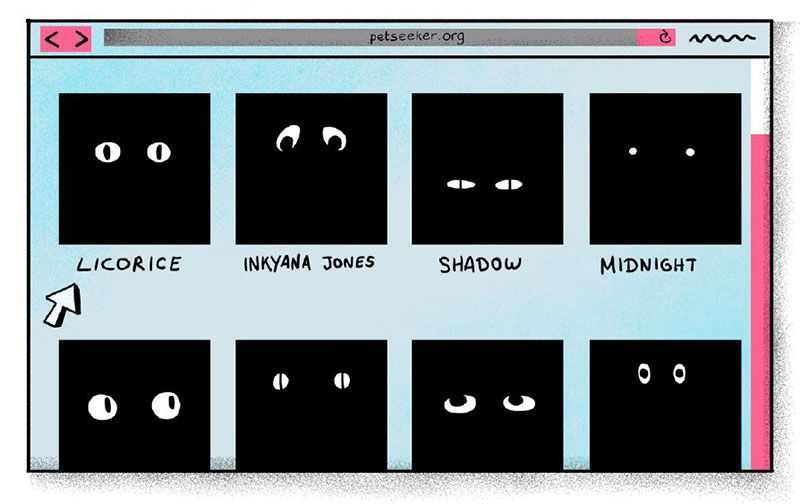

Fact: Black animals and pit bull-type dogs are highly adoptable.

First, if you’re labeling all stocky dogs as “pit bull-mixes” and black-and-white dogs as “black,” the records of the animals in your care—and your conclusions about their adoptability—might be inaccurate from the get-go.

The truth is, it’s very difficult to accurately determine breed—today’s dogs are a smorgasbord of mixed breeds, and a 2012 Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program study showed that animal professionals correctly identified breed less than one-third of the time.

Black dogs and cats and pit bull-types are some of America’s most popular and therefore most abundant pets. They’re coming into shelters in higher numbers, but they’re also being adopted in higher numbers.

Although you can visually identify and record an animal’s color, a study published in the Society & Animals journal concluded that people perceived dog personalities based on breed, not color or size. So adopters aren’t associating black dogs with “bad” personalities, but adopters are susceptible to breed stereotypes. A recent study published in PLOS ONE showed that people considered pit bull-types equally as adoptable as other breeds—but only when they weren’t labeled as pit bulls.

In reality, black dogs and cats and pit bull-types are some of America’s most popular and therefore most abundant pets. They’re coming into shelters in higher numbers, but they’re also being adopted in higher numbers. You could adopt out more black dogs and cats and pit bull-types than any other animals and still have a surplus of sooty pets and blocky-headed dogs. If it seems like you have black animals and medium-size terrier mixes sitting in your shelter week after week, you probably do—but that doesn’t mean they’re not being adopted.

In 2013, the ASPCA’s Comprehensive Animal Risk Database System (CARDS) showed that although black dogs and cats made up the highest percentage of shelter intakes in 14 communities, roughly 10 percent more black dogs and cats were adopted than the next highest color (brown and gray, respectively). And CARDS data from 2014 showed that although dogs labeled as pit bull-types were ranked No. 1 in intake and euthanasia, they were also adopted more than any other type of dog except Chihuahuas.

“We’ve definitely seen an increase in people coming in looking to specifically adopt pitties,” says Vaccaro. “We do have a pretty high pit bull adoption rate, but we also have more pit bulls than other breeds.”

That doesn’t necessarily mean these longtime myths are all in your head—but maybe check your own recent shelter data to be sure it’s not confirmation bias. You may be paying attention to the animals who support your beliefs and disregarding the animals who don’t as flukes.

It’s likely that the animals who stand out—the tricolor tabbies, the single fluffy Pomeranian and the dog with a marking like a mustache—are adopted more quickly. It could be true that in your city, breed-specific legislation or housing restrictions discourage pit bull-type adoptions, or you’re particularly oversaturated with certain breeds or colors.

“It’s less about the people coming in with the stereotypes and more about the fact that we’re living in an urban situation where a lot of people live in an apartment building,” says Vaccaro. “We’re still seeing a lot of restrictions that prevent the dogs from being adopted.”

It could also be true that black pets are at a disadvantage because they’re harder to photograph well.

“If you feel like your black dogs always sit there—what if you’re right?” asks Suzanne D’Alonzo, HSUS manager of strategic engagement. “Are you taking black-and-white pictures in a poorly lit room? Because those are not going to be great on Petfinder. You need to have a flash and high resolution to really show off a black animal in a photograph.”

D’Alonzo worked at a Virginia shelter for 15 years. Due to policies set by its board, staffers originally couldn’t adopt out pit bull-types and, over time, could only adopt out the dogs after adopter housing and insurance checks. It took a long time for breed messaging to wear off.

“Shelters feared what the dogs could be like or could be used for, and we put a lot of fear out. We made them sound horrible. We had this decade-plus delay where people caught up” to adopting dogs commonly labeled as pits, says D’Alonzo.

But now she sees people of all ages and socioeconomic levels adopting the dogs. In particular, she says, adopters in neighborhoods overlooked by traditional shelter and rescue messaging seem to be more open to adopting all kinds of breeds. They don’t know what all the uproar is about; they never got the message. For them, the stigma might have never existed.