Smart lending practices

A little technology and methodology can help protect your investment in TNR equipment

When the humane box traps she’d purchased for about $70 each started showing up at local garage sales, Leah Kennon issued an ultimatum: “I’m not buying any more traps until we track the ones we have,” she told her staff and volunteers.

It wasn’t the first time that Kennon, operations director at the Feral Cat Coalition of Oregon (FCCO), sought to bring order to her organization’s trap-loan process. Years earlier, she had replaced a “really loose” system that relied on paper forms with one that used an online spreadsheet. The system could have worked, she says, but at the time, all FCCO’s equipment was stored at staff and volunteers’ homes, and Kennon couldn’t convince them to update the spreadsheet in real time. “They just wanted to enter stuff once a week.”

In the end, they were still losing too many traps.

It’s a common dilemma in trap-neuter-return (TNR) programs. To get large numbers of community cats sterilized, organizations must equip caretakers and grassroots advocates with the training and tools they need for trapping, says Danielle Bays, community cats program manager for The HSUS. That typically entails operating at least one “trap depot”—which could be an office, a storage shed or a volunteer’s garage—where people can borrow and return equipment.

At any given time, an organization may have anywhere from dozens to hundreds of traps in circulation, along with other tools like trap dividers, carriers, drop traps and holding cages for sick or injured felines. It may have trap depots at multiple locations and dozens of people involved in the lending process. On top of the constant borrowing, re-borrowing, trading and partial returns of equipment, there are also the emergency loans—for the cat who may be pregnant, or the kitten who looks injured—when record-keeping tends to go by the wayside. Combine all that with staff and volunteers who are often overwhelmed and juggling multiple priorities, and it’s easy to see why large and small organizations alike struggle with keeping track of their traps.

“I talk with a lot of people who just give up,” Kennon says.

For FCCO, the solution entailed a bit of technology and a more methodical approach. Kennon purchased a scanner and a database program called FileMaker Pro, which a volunteer programmer customized for the organization’s needs. She and her staff assigned each of their 300 traps a bar code, which they then printed, laminated and attached to the trap with a zip tie. Staffers store client contact details in the database and then simply scan the bar codes whenever the person borrows or returns equipment. It takes some of the human error out of the equation, Kennon says, and forces staff to record transactions as they occur.

They put bar codes on carriers, too, and “lo and behold, you can actually get those back,” Kennon says. “We never saw those come back. We see the majority back now.”

Once a week, a staff member or volunteer calls people who have kept equipment past the loan period. This provides not only a needed nudge, but also an opportunity for FCCO to check in with people about the status of their cat colonies and to help troubleshoot any problems they’re having, Kennon points out. The end result is that “our trap room hasn’t been empty this year, which might be a first!”

Order versus easy access

Operation Catnip of Gainesville is another organization that means business when it comes to its cat traps. The Florida group coordinates monthly high-volume spay/neuter clinics for community cats and often has as many as 400 traps—representing about $30,000 worth of equipment—on loan to members of the public.

“We take our traps very, very seriously,” says program coordinator Melissa Jenkins. “They’re the bulk of what we do and how we can help people.”

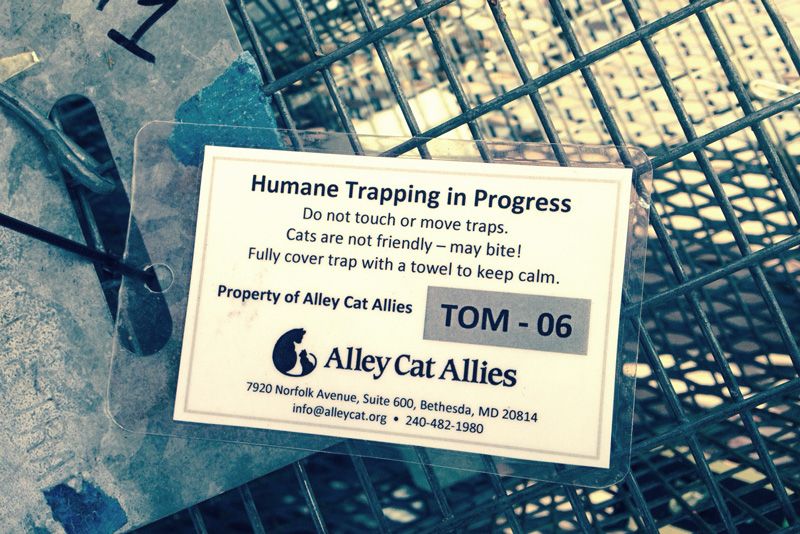

Two years ago, Operation Catnip streamlined its trap-loan process by placing QR codes, printed on weatherproof bumper sticker material, on all its traps. Staffers use their smart phones to scan traps during checkouts and returns; EZRentOut, an online software, stores the details and borrower contact information and provides a printout with reminders about due dates, late fees and the organization’s humane trapping policies.

In Jenkins’ experience, successful returns start with the first conversation between the organization and the borrower: She makes it clear that the trap is a loan and that the loan requires a credit card number as a security deposit. When picking up traps, people must sign a loan agreement, promising to use the traps only for TNR and to pay for any equipment that is lost, damaged or stolen.

Whether in the form of a credit card, cash or check, security deposits are a vital part of protecting your investment in equipment, says Jenkins. A common strategy is to simply hold a check or credit card number during the loan period. (At FCCO and Operation Catnip, credit card numbers are kept under lock and key. To prevent concerns about hacking, card numbers aren’t entered in the organizations’ online systems, and the paper forms they’re written on are shredded or returned to clients after the equipment is returned.)

While deadlines are important, given the unpredictability of cat trapping, some flexibility is necessary, Jenkins says. When people need traps beyond the loan period, Operation Catnip is happy to grant extensions and only charges a card when the borrower ignores repeated calls to return equipment. People rarely end up paying for traps, but some need that extra push to make returning equipment a priority. “When you charge someone’s card,” she says, “they call you back pretty fast.”

One challenge to crafting a trap-loan system, says Bays, is that you must balance the need for an orderly process with the goal of making it as easy as possible for people to borrow equipment. For example, if you have a trusted volunteer who lends traps for four hours on the first Saturday of the month, and that’s the only time members of the public can get traps, you may have no trouble tracking your equipment, but you could be creating a barrier to people doing TNR.

Geographic accessibility can also be an issue, particularly if you’re the only organization lending traps in a large area. Although it’s usually easier to keep tabs on your inventory when you have just one trap depot and a limited number of people handling loans and returns, you may need to branch out if people can’t easily get to your facility. “You’re loaning traps for a reason,” says Bays, “and your processes should support your overall goal of getting more cats sterilized.”

FCCO handles most of its equipment loans at its office facility in downtown Portland, but it also maintains several smaller trap depots at the homes of volunteers outside the city. “People are coming from all distances, and traffic has gotten really bad,” says Kennon. “We’re right in the city, so it’s a barrier.”

While tracking equipment at the satellite depots was once a problem, Kennon found that giving volunteers extra training and a sense of accountability made a big difference. Now, FCCO is thinking about establishing another trap depot 10 miles north of Portland in Vancouver, Washington.

Bays encourages organizations to emphasize the importance of the trap-loan system to their staff and volunteers. It’s not only an essential part of a high-impact TNR program, she says, but an opportunity to meet people in your community who are concerned about cats, some of whom could turn out to be your next trapping superstars.

And if you’re still struggling to keep your inventory straight, Kennon has this simple mantra: “Don’t give up. Traps are money, and traps are cats.”