So your co-worker is the worst

How to work with 'difficult' people in emotionally charged environments

You co-worker does it again. They forget (or ignore?) your instructions. They speak to you in that condescending way. They complain loudly and incessantly about your boss; they take credit for your work in a meeting and gladly accept the praise; they make a mistake and then stretch the truth to get out of admitting fault; they ignore your years of expertise and just do tasks as they think best.

You might consider these people frustrating or difficult. And when you’re regularly dealing with situations that impact animals’ lives—deciding whether to return that friendly outdoor cat to his colony or adopt him out, how to handle that reactive dog, if you should portalize cat kennels or maximize shelter capacity, how to enforce sanitation best practices—you might even begin to consider them evil.

You have imaginary sparring matches with them while you’re driving to work or as you’re trying to fall asleep. Your spouse has banned mentions of them from your home because they’re all you can talk about. This person is, as advice columnist Ann Landers once wrote, living rent-free in your head.

Are you thinking of that person right now? How do you feel? Is your whole body tensed, ready to fight? Are your teeth gritted, is your blood pressure high, are your shoulders up somewhere near your ears?

Breathe. Unclench your jaw. It’s time to evict your squatter.

The reflexive loop

When my boss asked me to write an article on dealing with difficult people in the workplace, I wondered if he was making a little passive-aggressive joke. I am not known for my easygoing nature: I can’t stand long, drawn-out discussions (make a decision!), and if I think I can do something better than you, I want you to get out of the way so I can do it.

So I might be other people’s difficult co-worker. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have difficult colleagues of my own. In fact, all of us might be someone’s difficult co-worker. And that’s a great place to start when thinking about how to deal with the people you just can’t stand: Leaving out actual unlawful behavior or the possibility that your co-worker is a true psychopath (shh, stop cackling sardonically and admit that your co-worker is most likely not a psychopath), you could be as much to blame for the difficulties as the other person.

“Some people are going to be more contrarian,” admits Laleh Eshkevari, acting senior vice president of human capital and development at the Humane Society of the United States. “But it’s also a perception thing, so in your eyes somebody could be difficult, and in my eyes somebody could be simply advocating for themselves. The more helpful way to think about it is what’s the most skillful way to interact with somebody, and the more I avoid labels like ‘difficult,’ the easier I’ll be able to interact with that person because I haven’t now put a label on them.”

Lauren Glickman, principal consultant at Foray Consulting, a group that helps mission-driven individuals and groups build emotional resiliency, says there are very few truly difficult people, only difficult conversations that you aren’t having with them. “We can’t actually avoid this difficult conversation; it’s just: Is it happening silently inside our own head? Or will we allow it to be productive?” she says.

Glickman believes that many people have “disempowered relationships” with their own discomfort, which leads them to avoid having difficult conversations and behave in unhelpful ways, such as complaining about a behavior to everyone except the person exhibiting the behavior. “It can become a compounding effect,” she says.

This is also known as “the reflexive loop,” or confirmation bias, and it goes hand-in-hand with “the ladder of inference,” a mental model developed by the late Harvard professor Chris Argyris that helps explain why it’s hard to change people’s minds about, well, anything. We observe “data,” then select what data to process, then make assumptions based on that selected data, then draw conclusions and take action based on those conclusions. In a reflexive loop, if we already dislike someone, we’re going to select the “data” (the behavior we don’t like) that aligns with our existing dislike and draw conclusions and take action accordingly.

Is that a true story? Or am I just making up a story in the absence of more information?

“I would say 100% of people have done this, which is create victim-or-villain stories,” says Eshkevari. In these mental narratives, “the other person is not just another human being who has a different perspective, but a horrible person who really just wants to purposely ruin your day. So if you’re aware that you’re creating a story, at least once you have the awareness you can go, ‘Is that a true story? Or am I just making a story up in the absence of more data, more information?’”

Argyris wasn’t alone in pointing out peoples’ tendencies to make flawed assumptions: One of the tenets of the popular self-help book Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High is that people should “look within” before approaching potential conflict. This also aligns with Glickman’s philosophy, but she additionally advises people to literally look within in intense situations and unclench their pelvic floor (the muscles that control urination), which can set off a domino effect that unclenches your other muscles. If you tense up whenever your difficult co-worker is around, simply loosening up can tell your body that it’s not a fight-or-flight situation that requires a fight-or-flight response. In other words: Relax (but don’t pee yourself).

Eshkevari formalizes the “look within” approach by organizing mindfulness workshops for staffers at the HSUS. “I’m a big fan of taking a breath, or thinking about where my feet are, really sinking into the chair that I’m sitting in, really being aware of where I’m touching the chair. It forces you to become aware of your thinking … the thinking of ‘this person’s difficult.’ Nobody on the planet doesn’t have that thought about somebody. But that’s the thought, and I can just be aware of that thought, and I don’t have to buy into that thought.”

This advice applies whether your difficult person is a peer, a boss or a subordinate, and regardless of gender. But if you’re in a role that may give you an upper hand, it’s even more important to be self aware, says Glickman. “You can be the best feedback giver in the world, but if the person you’re talking to has no desire [to listen], it’s not going to work. One of the things that we can do to make conversations go well is learn how to be a good feedback receiver.”

“The appropriate use of power is ‘power with’ as opposed to ‘power over,’” adds Eshkevari. “Am I exercising power with this person, or am I trying to overpower them with my voice?”

Am I exercising power with this person, or am I trying to overpower them with my voice?

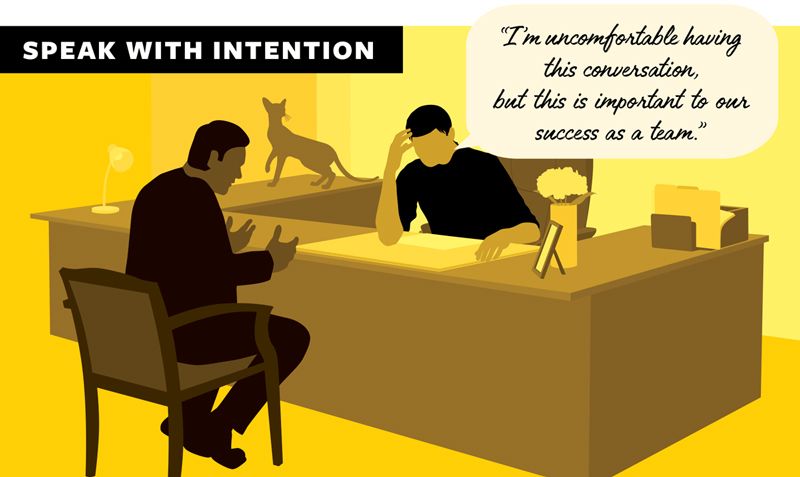

Conversation vs. conflict

Glickman points out that interpersonal communication isn’t something that’s typically taught in schools or something you can practice alone; it’s something that must be learned publicly, through trial and error—which can be terrifying. Everyone lives in their own reality, she says, with notions and ideas about how they’re supposed to be and not supposed to be. “Some people think about disagreement as conflict, and other people think about disagreement as conversation,” she says.

While everyone living in their own reality may sound a bit New Age, it’s true that we were all raised in different ways and we’ve all had different experiences that shape how we interact with the world. Previous trauma or vicarious trauma (aka compassion fatigue) powerfully contributes to that reality. “Hurt people hurt people,” says Eshkevari. “There might be pain that’s being transmitted that you don’t know about.”

When a co-worker is behaving badly, you can try to limit the time you interact with them to protect yourself. And some bad behaviors really do need to be reported to and dealt with by HR and management. But if you’re struggling with a conflict that isn’t actual bullying or harassment, but a failure to see eye-to-eye, you can also try to get to know your perceived antagonist in a different way, says Eshkevari. “Even acknowledging that people have birthdays, weekends. You might get some new information, some data that’s going to help you understand,” she says. “Then you’re starting to build a relationship, and in the context of the relationship, it’s a lot easier for you to come and say, ‘When you did X, it made me feel Y.’”

Glickman looks at high-intensity work environments through a framework: Everyone needs to be grounded in reality. Everyone needs to find their work meaningful in some way. And everyone needs the tools and the courage to improvise inside of their own reality. She says the reality is that most discomfort is temporary, and if we act as though discomfort is something neverending that can’t be solved, we’re not grounded in reality.

“You can’t practice difficult conversations in private,” she says. “We have to be able to tolerate the discomfort of learning publicly. If we believe conflict is only uncomfortable, and we have a disempowered relationship with it, it’s going to be so difficult to have that conversation. But if we believe conflict is one of the biggest opportunities to build trust in a work group, or we believe conflict is one of the biggest opportunities to grow as a human being, so we have a willingness to be uncomfortable in service of our mission, then we might actually be able to build some skills and learn in public.”

Personally, I’m firmly in the “disagreements are conversations” camp, so what about us bulls in china shops who have no problem saying what’s on our mind? Chances are, if you work for animals, you’re an advocate—a great thing to be!—by nature. But as Eshkevari points out, it can be a tinderbox when so many advocates work together, and both passive and aggressive people can benefit from not only being brave enough to have difficult conversations, but having them the right way.

“Get your motives right. Start with heart,” says Eshkevari, referencing the Crucial Conversations trainings she holds for employees. “If my motive is ‘I’m going to prove you’re a difficult person in this conversation,’ it’s going to go really differently than if my motive is to help us get to the best possible solution. Then you can actually use your motive if the conversation goes sideways. Sometimes you mess up and then you have to come back.”

Eshkevari recommends identifying your core values—how you’d want to be known if, say, you died tomorrow—and think about conflict in terms of those core values. For example, it might drive you nuts when a co-worker is late because one of your core values is fairness, and you don’t feel it’s fair for other employees to have to cover for the perpetually tardy. Once you identify why something or someone is bothering you, it’s much easier to either gain the self-awareness to recognize your pet peeve isn’t reasonable, or to approach justifiable disagreements in a positive, inclusive way.

Your core values can serve as a guiding light while you’re having a difficult conversation, says Eshkevari. “Principles before personalities,” she says. “Use them for how you approach a conversation. No matter what happens, you showed up the way you wanted to show up, which is what matters in the end.”

Start with heart

So what are your core values? According to the VIA Institute on Character’s “character strengths test” recommended by Yale professor Laurie Santos, my own top strengths include judgment (thinking things through and examining from all sides, being able to change one’s mind in light of evidence), appreciation of beauty and excellence, and bravery (not shrinking from a difficulty, speaking up for what’s right even if there’s opposition). (Note that personality tests can be a great way to think deeply about yourself, but they shouldn’t define you.)

Positive traits, perhaps, but ones that can turn sour in the wrong circumstances: I’m quick to judge; I’m dismissive of things that don’t meet my standards; I will speak my mind even if it means burning a bridge. There’s a shadow side to everyone’s core values, and identifying your own can help you use your core values for good and not for flogging your co-workers (or friends or family members!). If one of your pet peeves is people who don’t speak up, consider that what you may see as cowardly, those people may see as strategic, a way of keeping the peace for the greater good. And there can be solid reasons for either approach.

How can I approach this disagreement in an inclusive way?

Glickman recalls a conversation she had with a shelter veterinarian who worked in a shared exam and medical supplies room. The veterinarian kept turning to the gauze jar mid-euthanasia, finding it empty and having to interrupt the euthanasia to find more gauze. This seemingly tiny gauze issue was eating away at her.

By leading the veterinarian through an intention exercise, Glickman helped her figure out why the gauze meant so much to her. Why was the empty gauze jar so bothersome? Because she wanted to do her work uninterrupted, said the veterinarian. And why did she want to do her work uninterrupted? Because it was really important to do a good job, she said. And why was it important to do a good job? Because it was one of the most important moments of these animals’ lives, and she wanted to honor each and every animal, she said.

So it wasn’t about gauze, says Glickman. It was about how when her co-workers forgot to refill the gauze jar, the veterinarian felt they weren’t working with her to honor these animals’ lives. But it was also true that the room was “completely inadequate” for the shelter’s volume of intakes, exams, surgeries and euthanasias.

“And that’s what the conversation ended up being about, and they made a lot more changes, given the constraints they were facing. They changed a couple key things that made a huge difference in how that room was used and how supplies got handled,” she says. “Lead with intention and get at the heart of why you want someone to be on time [for example]. It’s not about them being on time or being late, it’s about the mission, the team. Always choose an intention that’s inclusive of the person you’re talking to.”

That’s the great thing about working with difficult people at emotionally charged nonprofits: In the end, the intention is almost always about the mission. And that’s something we can all agree on.