Taking care

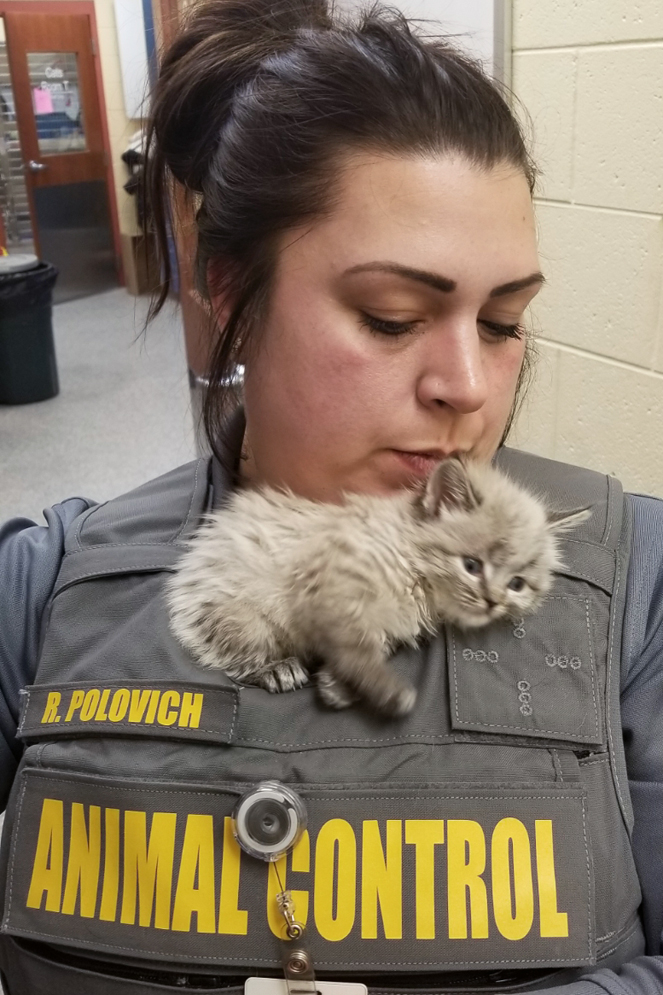

Animal services officers stay safe with caution and compassion

In 2012, Denver animal protection officer Daniel Ettinger was dispatched for a simple dog-at-large call. He found the dog, but things soon went awry—and not because of the animal.

The dog ran back home, Ettinger followed, and he found himself facing a man outside the property. The man started swearing and yelling at Ettinger, confused about why he was there.

“The dog owner was extremely aggressive, and I was intimidated,” Ettinger recalls. “I felt like I couldn’t handle the call by myself.” He called the police, who helped him issue a ticket for a leash law violation.

It was a standard encounter: In Ettinger’s field, the work is tense and unpredictable by nature, and people in distress can sometimes pose safety concerns. But Ettinger regretted getting the police involved in such a relatively minor situation, and with time he learned other ways to respond to humans on the job—skills that any animal services officer can wield to better serve their community and to keep themselves safe. Now he uses his experience to train other officers.

“We want to create an environment where we have empathetic, trauma-informed animal protection officers who can help people in the community and help animals in the community,” Ettinger says. “We want to be respected, and we want people to understand we’re here as a resource.”

Here, Ettinger and other animal services veterans share what it takes—from individual officers and the organizations that employ them—for officers to stay safe and compassionate in their community interactions.

The human element

Animal services officers face a wide range of dangers on the job: fearful dogs, cat-filled homes thick with ammonia fumes, injured wildlife, exotic pets on the lam. But the people they meet can sometimes pose challenges, too.

“The pets we’ve pretty much got down,” says Mark Kumpf, director of Detroit Animal Care. “ … We can read animal body language; we know what their instincts are. But when you deal with people, we don’t know what’s going on in that head.”

While violent attacks are uncommon, they do happen: There was the animal services officer held hostage in a Florida home in 2019 after she investigated a complaint about a dog without proper shelter. There was the officer shot and killed in California when coming to safeguard animals in a home after an eviction in 2012. There was the officer shot and wounded in Baltimore in 2009 after responding to a report of dogs kept illegally in a home.

Kumpf himself has written that he’s been threatened, assaulted “and even run down by a suspect attempting to avoid a ticket.”

Ettinger says officers should assume any call could present a safety concern.

“We’re dealing with situations that could go bad very quickly. We may have to take the animal for investigation, and that is one of the hardest things you have to do. … You are absolutely removing a family member [from a home].”

Lately, Kumpf says, emotions are running even higher than usual.

“You have a lot of pressures on pet owners. The recent pandemic, the economy, the state of affairs in general all translate into how they react and respond to animal issues.”

Ettinger agrees: “The risks of the job will continue to increase as we move forward in the current climate that we’re in. It’s important to understand that we as a profession have to continue to grow with potentially dangerous situations.”

“There’s no need to be that tough, arrogant, macho person. We just need people who are empathetic.”

—Daniel Ettinger, Denver Animal Protection

A checkered history

Part of the tension, Ettinger says, is how animal care and control agencies have historically approached the job—back when their officers were widely known as “dogcatchers.” He says this image still fosters distrust in communities, even as the field has evolved.

“We have to realize that the whole dogcatcher thing isn’t made up,” he says. “The dogcatcher was a representation of the product we put out there years ago, and we are still working toward showing people that we are not that person anymore. And it shows in every contact that we have.”

During a virtual training for animal services officers this summer, Ettinger played a video of an officer responding to a call about a skunk. A bystander started filming the officer, who grew upset about the filming. She shouted at the bystander, ran toward him and called the police when the bystander wouldn’t stop filming.

“What would I have done differently?” Ettinger asks in the training. “So someone’s recording. The officer could have easily ignored the individual or said, ‘Hey, we’re looking for a skunk. Have you seen it?’ You didn’t have to go and get so aggressive with the individual for recording, which is that person’s right.”

“There’s no need to be that tough, arrogant, macho person,” Ettinger continues. “We just need people who are empathetic.”

A national reckoning

Approaching the job with empathy and compassion, Ettinger says, is even more important as the country grapples with protests sparked by police violence and racial injustice.

“Right now we understand the pressure we’re under as law enforcement or animal protection officers,” Ettinger says in his training. “It’s important the words we use are there to help people and not put people down or be in control of people. I think historically a lot of law enforcement agencies operated from a sense of control and power.”

Instead, Ettinger says the focus should be on demonstrating that animal services officers are there to serve the animals and people in the community—an attitude that should manifest in every interaction.

The trick is to take a “less authoritative, less controlling, less confrontational approach,” Ettinger says. He explains a gentler approach can often actually defuse situations and give officers more control—even if that feels paradoxical.

What’s more, Ettinger reminds his trainees that the people they encounter may be coping with a medical condition, addiction or homelessness. Officers can be more effective responders if they are trained and trauma-informed in these scenarios—or if they know to seek out a mental health technician who can come to the scene.

“Understand that crisis intervention is basically emotional first aid,” Ettinger says in his training. “If you’re not trained on that, there are opportunities to be trained and understand what resources are available to help people in those situations.”

“We’re here to be a civil servant, to help people in the community,” he continues. “And we don’t want to lose sight of that.”

Safety first: Ensure your field services staff have properly fitted ballistic vests and are supplied with and trained in the use of defensive equipment as a last resort.

Behavior that works

Ettinger’s class focuses on what’s called verbal de-escalation. It’s about using tactical language and behavior to calm emotions, defuse tensions and resolve conflicts.

The technique lays out smart steps from the greeting to the closing (see “Tactical tips,” below). One simple principle is just giving the person time to speak—allowing space for a two-way conversation.

“It’s really important to listen to what they have to say, because most people want to be heard,” Ettinger says in his training. Then “you’re making a decision based on the totality of the situation, and doing it in a manner that’s going to be respectful, polite and professional.”

Another tactic officers can learn is called situational awareness, or being alert to your surroundings and potential threats. Chris Schindler, vice president of field services for the Humane Rescue Alliance, headquartered in Washington, D.C., says all of his new officers spend up to three months learning the city and the roads before they go out on their own.

“You have to always be paying attention to what’s going on around you,” Schindler says. “It might not be the call you’re on that could be problematic; there’s all these things going on in the background.”

Investment that counts

Of course, safety protocols don’t rest solely on the officer. While the ownership of animal care and control services varies widely across the country—from police departments or other government agencies to nonprofit shelters—every organization should prioritize resources for training and safety precautions.

“Safety of our officers is of utmost importance,” Schindler says. “It’s the thing that keeps you up at night, making sure your people are safe and have the tools they need to do their jobs.”

Schindler oversees humane law enforcement and animal control divisions in New Jersey and the D.C. area. All of his officers wear ballistic vests that are properly fitted, get certified in using retractable batons and pepper spray, and attend ongoing trainings on standard operating procedures. Part of the training, Schindler adds, is teaching officers to use these tools only as a last resort for self-defense.

“Cost shouldn’t be a factor when looking at protecting our staff,” Schindler says, though he admits the price of ballistic vests can seem prohibitive. “There are grants out there for ballistic vests. I think they’re something all officers should be provided with.”

Schindler also recommends certifying officers to provide baton and pepper spray training in-house, rather than paying for external trainings. “It’s a huge cost savings down the road,” he says.

Kumpf says he’s “seen a lot of departments handing officers equipment but not training or certification that goes with it.” Other agencies, he says, have reduced officer trainings due to municipal budget cuts. And others still are struggling to host their traditional in-person trainings during the pandemic. But Kumpf emphasizes that training to handle animals humanely, interact with the public responsibly and, when needed, use equipment appropriately, should never be compromised.

If finding the budget for trainings is a challenge, Kumpf suggests that municipal agencies reach out to their risk management department for support. “They may sponsor the training,” he says. “They may look at it from the perspective of saving money for the city” by preventing future liability claims when untrained officers get injured.

Kumpf points out that plenty of organizations offer continuing education and professional development trainings, including virtual classes. Local police departments or sheriff’s offices may have technical trainings they can provide, and resources are available from national groups like the Humane Society of the United States, ASPCA and National Animal Care & Control Association.

NACA president Scott Giacoppo says overall, agencies have moved in the right direction—providing more training and protection for officers than in the past. He says more departments are now staffing a full-time officer who can provide formal in-house field training for officers, and he hopes NACA can work to help make these programs more consistent.

“Even if your agency isn’t a member of law enforcement, reach out and make those connections. If you haven’t taken your local precinct commander to lunch and had a talk about officer safety, do it. Just stay 6 feet away and get carryout.”

—Mark Kumpf, Detroit Animal Care

Partnerships and progress

No matter your organization’s setup, Kumpf says the key to success is remembering you’re not alone and being willing to ask for help.

As a first step, Kumpf suggests all officers get to know their local law enforcement partners. “Even if your agency isn’t a member of law enforcement, reach out and make those connections,” he says. “If you haven’t taken your local precinct commander to lunch and had a talk about officer safety, do it. Just stay 6 feet away and get carryout.”

Schindler’s department partnered with the Metropolitan Police Department in D.C. to get help executing search warrants. Now the police will help secure the individuals in the home and keep anyone else from entering while the humane officers do their jobs.

Less formal partnerships go a long way too, Kumpf says. He stresses the value of seeking advice from anyone who’s been in the field a long time. He says he’ll answer Facebook messages at 2 a.m. from colleagues who need help writing a search warrant.

“Ask the longest-serving person in your department to give you their knowledge,” he says. “You always can learn something from someone else. I learned how to trap a potbellied pig in a dog trap with bologna and bread. I learned how to handle an alligator and wrestle with snakes because I’ve been humble enough to ask folks to teach me.”

After all, it’s the individuals and organizations working in animal protection who have helped professionalize the field and worked to better serve the people and animals in their communities.

“I can’t say how far we’ve come,” Kumpf says. “It’s light years from where we were. We have a lot of people to thank for that, from the HSUS to ASPCA to [the mom] who wrote a letter to her mayor to say her son the ACO needs a ballistic vest.

“Animal control used to be the four-legged trash control. State statutes have changed. Public opinion has changed. They recognize we’re not dogcatchers anymore. We’re animal welfare professionals.”

There’s still plenty of room for progress—for greater consistency in safety standards, emotional and physical protection for officers, and training in the skills that lead to positive interactions with community members. And while officers in many communities can refer pet owners to resources—such as free weather-proof dog houses, pet food assistance or subsidized veterinary care—these vital support services aren’t available everywhere. But Ettinger is thankful for the progress that’s already been made and hopeful for the future. And he thinks, at the end of the day, it’s all worth it to serve the animals.

“It may sound silly, but I can actually look into an animal’s eyes and see its emotion, whether it’s pain or discomfort, but I can also see its thanks,” he says. “Being that voice for the voiceless is what keeps me going.”