Virtually there

How the lessons of COVID-19 are ushering in a new era of veterinary telemedicine

When Stacy LeBaron's elderly, FIV-positive hospice cat came down with a painful eye infection in March, she wasn’t sure where to turn. In addition to autoimmune issues and renal disease, Hooch was an anxious traveler, and his veterinarian was an hour away. The practice was also limiting visits because of COVID-19.

LeBaron, who lives in Warren, Vermont, and hosts the Community Cats Podcast, asked her veterinarian if she would be willing to try a virtual exam using FaceTime.

“I was the first telemedicine visit they ever had,” LeBaron says. “My 16-year-old son helped—so one of us held Hooch, one of us held the computer. The vet would ask, ‘Can you move the camera left or right?’”

The veterinarian prescribed a variety of medications to cover several bases, and LeBaron drove to the clinic, where a staff member came out wearing protective gear and gave her the meds. There were several more follow-up calls over FaceTime, and Hooch’s eye infection cleared up with antibiotics.

Several weeks later, Hooch died peacefully in his sleep. LeBaron says that the virtual care the veterinarian was able to provide saved him a lot of pain and discomfort in his final days.

She’s not the only pet owner who has recently discovered the benefits of virtual care. While the veterinary profession has been slow to embrace telemedicine compared to the human health field, COVID-19 has forced a lot of change, says Dr. Hilary Jones, founder of veterinary telehealth platform TeleTails.

In the wake of state stay-at-home orders and social distancing guidelines, veterinarians across the country lost in-person access to many (and, in some cases, all) of their clients and patients. Many turned to telemedicine and telehealth to bridge the gap to triage animals and provide critical care.

As shelters and private practices quickly realized, making the switch to digital comes with legal and logistical challenges. On the up side, the transition to virtual care is showing that even the most basic tools of technology can benefit veterinarians, pet owners and shelters, and it could dramatically expand access for those in underserved communities who routinely face barriers to obtaining veterinary services.

Telemedicine, telehealth and the law

The words “telemedicine” and “telehealth” are often used interchangeably, yet they encompass a different range of practices. In their 2018 publication “The Real-Life Rewards of Virtual Care,” the American Animal Hospital Association and American Veterinary Medical Association make key distinctions between the terms. Telehealth includes “all uses of technology to deliver health information, education, or care remotely.” Telehealth can include veterinarian-client communications (or communications from clinic or shelter staff, including technicians and front desk staff), along with medical providers’ communications with one another, such as professional consults done electronically or over the phone.

A subset of telehealth, telemedicine involves “the use of a tool to exchange medical information electronically from one site to another to improve a patient’s clinical health status.” Generally, telemedicine uses technology—whether a phone call, video meeting, text or email—to diagnose a condition and prescribe treatment.

“We’ve kind of always had telemedicine in that we call the vet and describe what’s going on,” says Lindsay Hamrick, director of policy for companion animals at the Humane Society of the United States.

But within this narrower category are more legal restrictions, most notably the requirement in most states’ veterinary practice acts for a veterinarian-client-patient relationship.

Under the VCPR, veterinarians need to have physically examined an animal before they are allowed to provide telemedicine services. In some states, regulations require a VCPR to be established not just for each animal, but also for each medical condition.

Though some regulations have been relaxed during the pandemic (see “Changing legal landscape,” below), many veterinarians still face the difficult choice between breaking the law and withholding care from animals who need it. But the physical examination requirement of the VCPR might not be the roadblock it’s made out to be, especially for shelter veterinarians dealing with COVID- 19, says attorney and veterinarian Dr. Charlotte Lacroix, founder of Veterinary Business Advisors.

For a shelter veterinarian, there is less likelihood that treating an animal owned by the shelter would result in legal action. “When you’re in the private practice world, the risk is much higher because now you’re dealing with a client’s pet.”

“Medicine requires a judgment call,” says Lacroix. Something that may be technically forbidden, such as treating an animal virtually without a VCPR, may be a risk for the veterinarian, but not treating could be a huge risk for the animal, and by extension the client. “In such circumstances, it is important to have the right narrative and the complete documentation,” says Lacroix. “At the end of the day, as a professional, we must always do the thing that’s in the best interest of the patient.”

Lacroix also stresses that an emergency isn’t only when an animal is in dire straits, but when the owner is as well. “Not being able to get out of your apartment for days or weeks can make something an emergency,” she says, adding that while this type of situation has been prevalent during COVID-19, for those who suffer physical or mental health challenges or who otherwise have trouble accessing veterinary medical care, telemedicine can offer essential support.

Lacroix says, “I am pro telemedicine because I want to leave this in the hands of my colleague veterinarians to decide what is in the best interest of their patients. I trust them to make the correct judgment based on the situation.”

Another tool for bridging gaps

Those who work with underserved populations are accustomed to challenges. In that way, groups such as Pets for Life, an HSUS program that serves pet owners who face financial, geographic and other barriers to veterinary care and basic pet supplies, are uniquely positioned to respond to the additional challenges posed by COVID-19.

In 2016, the Wisconsin Humane Society, a PFL mentorship partner, began a collaboration with the Shelter Medicine Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine in which veterinarians, along with fourth-year veterinary students on clinical rotation, accompany the PFL team on community visits to targeted neighborhoods of Milwaukee. PFL staff use a master spreadsheet to track clients’ needs, ranging from social services for the humans to flea and tick medication for the pets. When there’s a medical need, the client goes on the visit list for the UWSMP team.

When COVID-19 put an end to the community visits, the team quickly pivoted to implementing new ways to serve clients, including telehealth and telemedicine. “It was a painful decision to put the in-person visits on pause because we know what a difference it makes,” says Jill Kline, vice president of community impact programs for the Wisconsin Humane Society. “So when the option for telemedicine came up, we were so excited.” After conferring with the UWSMP team, they switched to virtual visits. “Depending on the client’s access, we’re either doing a Zoom meeting with the UW vet, our staff, the client and the pet, or if clients don’t have [internet] access, we have the capacity to do a three-way call and the client can text pictures [of the pet] if needed.”

Kline says that they tend to see a lot of skin and ear issues, which can typically be addressed through virtual consults. As part of the transition to online services, PFL staff set up an account with an online pharmacy. A UWSMP veterinarian sees a client online, then enters prescription information. The PFL staff authorizes payment, and the medication is mailed directly to the client.

During one of the first client calls, veterinary intern Dr. Christina Barrett was able to diagnose and prescribe medication for a dog’s ear infection. According to Wisconsin’s VCPR guidelines, veterinarians can only diagnose and prescribe if a client and their pet have seen one of the UWSMP veterinarians previously. In cases where there is no VCPR, the veterinarians can still provide advice via telehealth. For example, veterinary intern Dr. Emily Pellatt consulted with a client whose dogs had skin problems, talking them through options for over-the-counter medications and treatments. For cases where the need went beyond what telemedicine and telehealth could provide, PFL staff transported the pet to the shelter’s temporarily closed spay/neuter clinic, and a veterinarian working with that facility treated the animal there.

Dr. Alex Ellis, a Maddie’s Fund shelter medicine resident at UW, says even with the limitations in place, doing something for people with animals in need “is always better than doing nothing. Even if it’s just telling them ‘You need to go to a veterinarian,’ that can be really helpful.” He adds, “I think the impact has been significant despite the limitation.”

For those who suffer physical or mental health challenges or who otherwise have trouble accessing veterinary services, virtual care can offer essential support.

Telemedicine: What works?

When it comes to integrating telehealth and telemedicine into their operations, shelters, rescues and veterinary clinics are taking a multifaceted approach. Some, especially private-practice veterinarians, are enrolling in formal digital platforms created for this purpose. These can be especially helpful for those wishing to use the platforms to share medical data with colleagues or make use of payment features. Formal telemedicine platforms are nice for some, but many organizations, especially shelters and rescues, are turning to mainstream digital platforms, such as Zoom or FaceTime, or simply using a combination of emails, texts, conference calls, digital photos and videos.

Dr. Nellie Goetz, a veterinarian who serves as executive director of Altered Tails, which operates two low-cost spay/neuter clinics in Arizona, says what we’re learning now in terms of telehealth and telemedicine will inform practices beyond the age of COVID-19. With the country likely to move in and out of varying stages of social contact restrictions for some time to come, it’s wise for organizations to create flexible plans for operation, and technology and virtual care will be a part of that.

When COVID-19 cases began appearing in Arizona, the clinic staff, who saw as many as 60 to 100 animals per day, immediately changed their drop-off process. They moved their reception table outside and implemented curbside check-in. When a stay-at-home order was issued and spay/neuter was deemed an elective procedure, Altered Tails closed temporarily. VCPR requirements in Arizona were relaxed because of the health emergency, and Goetz’s team looked for ways to offer virtual veterinary visits.

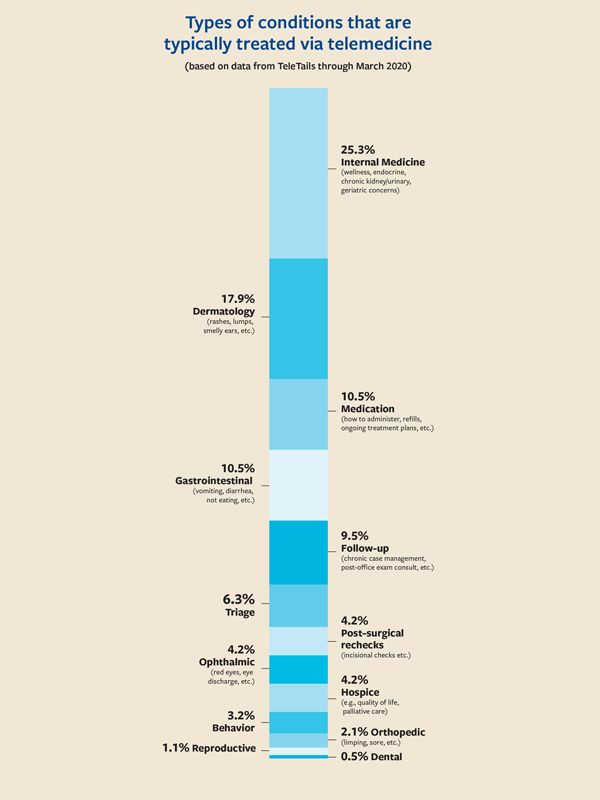

Telehealth and telemedicine can make the practice of veterinary medicine more effective and more efficient, says Jones. According to her company’s data, clients are far more likely to keep follow-up appointments if they don’t have to come to the office. Jones says telehealth is also extremely helpful for triage and for determining when a vet tech appointment would be sufficient, such as for an injection.

Goetz’s clinics frequently serve clients who live more than an hour away, so they are accustomed to using telemedicine for suture rechecks, where clients text or email a photo of the incision. When Goetz worked with an AVMA program serving tribal nations at the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, her team implemented telehealth for checkups. The veterinarians would visit the pueblo and set up MASH-style clinics for several days, then stay in contact with clients virtually. “Chronic conditions can be managed remotely for the most part,” says Goetz, who used video chats to monitor animals with issues such as hip dysplasia. “I think that’s one of the things we’ll see is moving toward managing more chronic cases with the telehealth aspect rather than having to have that animal come in every two weeks or every month.”

With countless households stepping up to foster animals during the COVID-19 outbreaks, shelters and rescues are leaning on telehealth and telemedicine to support them. Hamrick believes this presents an opportunity beyond the pandemic. “If fosters knew telemedicine was a routine resource, we would see an increase in the number of people who would be willing to bring animals into their home.” Jones agrees, adding that video calls to discuss behavioral issues and other basic challenges could make fostering easier on families, especially those who live some distance from a veterinarian or shelter.

Hamrick says that the extremely capable vet techs, medical directors and veterinarians are adept at triage and can determine what fosters can handle and when an animal needs to be seen by a professional. “There’s so much that pet owners and fosters can do right that we just haven’t trusted them to do,” she says. For her part, Hamrick fosters dogs in hospice care and is administering injections to her current canine. “The more we can build the confidence of pet owners and foster parents in terms of their ability to care for animals, the more animals are going to be in great homes,” Hamrick says. “And telemedicine is going to be a part of that.”

“If clients don’t have [internet] access, we have the capacity to do a three-way call and the client can text pictures if needed.”

—Jill Kline, Wisconsin Humane Society

LeBaron says, “For hospice situations [and] older kitties … especially higher-stress-level cats, I think telemedicine has a huge potential.” For example, veterinarians and technicians could use virtual care for an initial screen to decide whether a physical visit is necessary. She adds that regular virtual visits, such as 15-minute weekly check-ins, could also maximize time and resources for a shelter’s veterinary team and provide fosters with more easily accessible support.

Connecticut-based private-practice veterinarian Dr. Melissa Shapiro agrees. She offers in-home visits and when necessary sees clients at a local hospital, but also incorporates telemedicine into her practice. “A diabetic pet can need ongoing management and advice, and I can send the client home with a glucose meter and advise them on how much medicine to administer,” she says. “That’s a good use of telemedicine.”

Shapiro notes that a colleague of hers frequently uses telemedicine for end-of-life care, so animals who may have trouble getting around can stay at home, and their owners can use FaceTime or send digital images to the veterinarian. Shapiro also says virtual care is great for triage for rescue groups. “If they are not partnered with vets,” she explains, “they are going to need that help.”

“A diabetic pet can need ongoing management and advice, and I can send the client home with a glucose meter and advise them on how much medicine to administer.”

—Dr. Melissa Shapiro

A new model for care

Long before COVID-19 struck, access to veterinary care was a national crisis, says Dr. Michael Blackwell, director of the Pet Health Equity program at the University of Tennessee and former chief veterinary officer for the U.S. Public Health Service. Blackwell runs the AlignCare program, a Maddie’s Fund-supported project that uses a multiprong approach to helping underserved humans obtain medical care for their pets.

“Most of the families we are talking about are the working poor,” says Blackwell. “When these folks are asked to come to the clinic for a suture check, it’s a critical thing to be done, but they are often being asked to take off from work. They often don’t have paid leave … or private transportation. Then it’s, ‘It’s looking good, just let us know if anything changes.’” Telemedicine could alleviate such situations, says Blackwell. “Many families today have smartphones. They have a way to take a picture.”

The AlignCare plan includes a telehealth feature, which provides general information to answer people’s pet care questions. When clients are enrolled in AlignCare, an app links them to telehealth information, in addition to social services and veterinary service providers connected with the program. AlignCare is working to add telemedicine, and these efforts are being fast-tracked because of COVID-19. “With all of the applications for unemployment surging,” says Blackwell, “COVID-19 has exacerbated the problem we are addressing probably 10 times.”

Blackwell predicts that once people get used to the ease and convenience of veterinary telemedicine, there will be no going back.

Without a doubt, COVID-19 is changing the world of animal care and proving that with mindful collaboration, pet caretakers and medical providers can bridge the gap of physical separation. As Kline says, “It’s about being creative in how you can help.”

Document