Working together works

Retired president and CEO of Denver Dumb Friends League offers three parting words

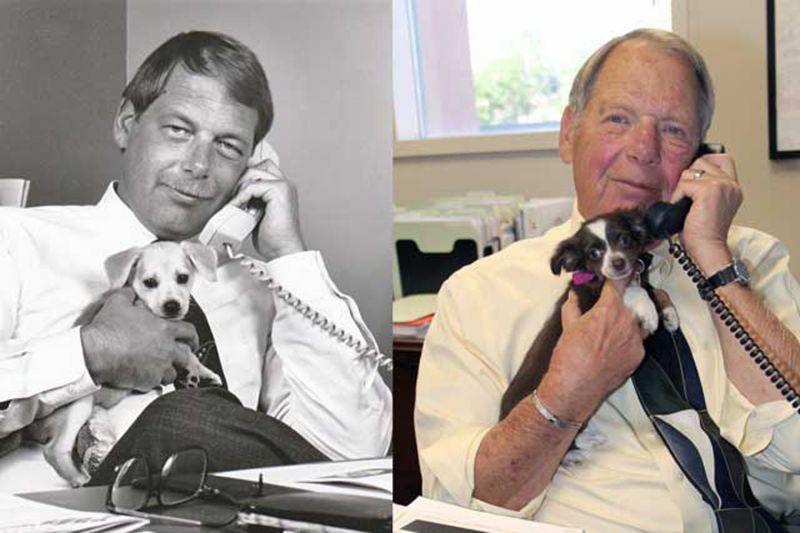

Bob Rohde was 23 when he joined Dumb Friends League as an animal care technician in 1973. (The Denver-based organization was founded in 1910, when the word “dumb” was widely used to refer to animals who can’t speak for themselves.)

Within four years, he rose to president and CEO. Over the next four decades, he led the League through seven expansions; the opening of the Harmony Equine Center and Solutions, a free spay/neuter clinic for all cats in Colorado; and the acquisition of Colorado Humane Society and SPCA, which works with more than 40 sheriff’s offices across the country to provide assistance in neglect and cruelty cases.

The shelter’s work with other animal groups and authorities, involvement in policymaking, use of paid advertising and establishment of a pet behavior support program were revolutionary at the time and set an example for other shelters. Rohde retired in February; in this edited interview, he reflects on his years at the forefront of the sheltering field.

How has sheltering changed since 1973?

The main thing that has changed is the communities are changing. Back in the “olden days” when I started, the Denver metro area was maybe half the size it is now, and we were handling 44,000 animals a year. When it came to handling adolescent animals compared to animals over a year old, it was probably a 50-50 mix. So tens of thousands of puppies and kittens were part of that 44,000.

And very, very few of the animals that came to us in those days were spayed or neutered. Now that our movement has been encouraging people to have your pets spayed or neutered for many, many years, if we get two or three puppies in from the community, it’s amazing. Kittens, we’re not quite there yet, but we’re certainly not handling the numbers we handled before. The biggest change is not so much the sheltering—it is the sheltering—but it’s the communities, where they have grasped the concept that number one, you shouldn’t breed your pet; number two, you shouldn’t take an unweaned litter [from its mother]; and number three, you should get your pet from an animal shelter.

Do you think community outreach programs, like the League's pet behavior support program, are what enable communities to get behind spay/neuter and adoption?

It depends on the community and the issues within the community. So I think you could have some excellent programs, but if your community’s not there, it’s going to take you longer to get there. You can’t just snap your fingers.

In Denver, for being a little, you know, “out in the cowtown,” the community really values companion animals. But it took running ads in the paper back in the early ’80s saying, “She’s already 6 months old, and she can multiply, so get your cat spayed or neutered.” When us old people started, it was not the thing to do to get a pet from a shelter, it just wasn’t, and besides that, your neighbor probably had a litter of kittens or a litter of puppies.

So once we started getting a handle on pet overpopulation, then it was on to the behavior and medical issues. We actually saw what San Francisco [Maddie's Fund] was doing and then took it a few steps forward. Currently, the League has nine people on the behavior support team plus 150 trained volunteers.

And just because we set it up one way doesn’t mean it was going to work the same way somewhere else. You can’t take a program from one organization and just plunk it in and say, “OK, make it work,” and we have never said that. It’s “here’s what we do, come see what we do, and see what works for you.”

You also pioneered the idea of a “customer service” approach to animal sheltering.

Over 20 years ago, we started an internal training of our team called “people care,” and our team has gone around the United States working with other animal welfare groups to get their teams trained. We haven’t done that for a few years, because more and more people understand customer service. I don’t like to use the term “customer service,” because when we started doing this, shelter team members felt that the animals were the customers, and we did an excellent job of animal care. We just also needed to do an excellent job of people care.

People make the difference for animals, and not just people within the shelter walls, so you need to engage those people, communicate with them. There are far more good people in this world than there are bad people, so how can we partner with them? How can we work together to solve the problem?

Back in the old days everybody outside the shelter walls was [considered] bad, because the staff felt they were causing the problem—and they were—but you’ve just got to wait for the community to catch up sometimes. They’re not bad. They just don’t know.

One of the other things, and I had absolutely nothing to do with it, but in 1974, when the Dumb Friends League built a new shelter, it was the first in the country to [display animals to visitors]. You know how you walk into shelters now, and in the adoption areas you see dogs and cats behind glass? The League was the first to do that.

Wow, I had no idea. Why do you think shelters were reluctant to “advertise” animals?

When I started—and I’m not whining!—I mentioned that we handled 44,000 animals. We had a team of 17 people, and we euthanized around 90 percent of those animals. Now we have a team of over 200 people and handle half that number, and about 5,000 of those are coming in from other shelters in our community and in the state and out of state, and we save over 90 percent.

Young people in the field now—no offense!—have no idea what it used to be like. If you’re getting in 44,000 animals and have a staff of 17 people, you’re just trying to keep your head above water because you might get 200 kittens in one day, and you know the next you’ll get another 200 in. And people were not lining up to adopt kittens or puppies from us.

Communities weren’t ready to move forward. [For example] back in the early ’80s, the Dumb Friends League and the local veterinary medical association (VMA) and the state VMA, we have an outstanding relationship now, but in those days we didn’t. I wanted to do in-house spay/neuter, and I said to the president of the veterinary association at the time, “We don’t want to have to euthanize all these animals, we need to get a handle on the population of pets. Let’s work out a deal.” And he said, “Nope, it’s your job to kill animals.” I'm a competitive person. If you tell me I can't do something, I'm going to do it.

[Editor's note: Dumb Friends League now spay/neuters all owned and unowned Colorado cats for free at its Solutions clinic—located in the state VMA headquarters. The League additionally partners with local organizations to spay/neuter unowned cats and offers two mobile spay/neuter clinics for both dogs and cats.]

At what point do you think pet adoption became more common?

Probably 20 years ago, it was coming on more and more. With [those] 17 employees, we didn’t have any volunteers. Now we have 1,500 volunteers. The community is just much more supportive. We kept over and over and over saying, “We need your help.” We didn’t say, “You’re bad people.” We said, “We need your help to solve this problem.” We always kept our numbers in front of people. We have never said we didn’t euthanize animals; we said, “However, if we had your help, this many more animals could be saved.”

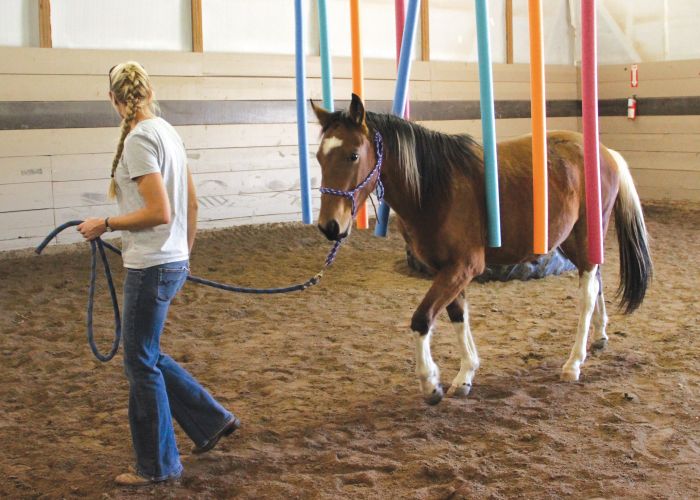

You were also instrumental in the creation of the Harmony Equine Center.

Back in 1910 when the Dumb Friends League was formed, in the articles of incorporation, it didn’t say just cats and dogs. It said “overdriven animals.” Well, that’s horses. When I started, we didn’t have the resources; we still had a huge mountain in front of us on cats and dogs.

So part of our strategic plan back in 2009 was to examine the need for an equine facility. We put together a task force, which included various representatives from the equine community, meaning veterinarians, trainers, inspectors, the state veterinarian’s office, law enforcement, to see if there was a need.

Sure enough, if I’m a sheriff in eastern Colorado and my county has a population of 1,000 people, and I have myself and a deputy, my budget’s very limited. There’s somebody out there not caring for their horses, and they need to be removed, but where am I going to take them? It’s not that the sheriffs didn’t want to do the right thing. It’s that their resources were limited.

Since 2012, we’ve handled over 1,300 horses, mules, donkeys and burros at Harmony, including some transfers from other organizations.

We thought we would be fortunate to place 50 percent of them, and the people in the equine community thought we’d be able to place 30 percent of them. We’re up past 70 percent. But that’s because there’s a huge investment in training. The average length of stay for those horses is 167 days, and it isn’t inexpensive, but we’re blessed to have donors who have a great deal of passion or compassion for horses.

Other than the Harmony Center, what’s one of the things you’re most proud of in your 45-year career?

We have good relationships with the Colorado Farm Bureau; we have good relationships with the Colorado Livestock Association; we have good relationships with the Department of Agriculture; we have a great relationship with the state sheriffs association. Those sheriffs get voted in by ranchers and farmers in agricultural communities. We don’t always agree, but they trust us.

Since the late ’90s, we’ve done many presentations, along with our partners in the Denver metro area, about building coalitions. We had a coalition in Denver of all the animal control agencies and the animal shelters in 1982. Nobody else had coalitions. I’m a big believer in working together works.

What motivated you to pioneer so many new approaches in the sheltering field?

I don’t like to call myself a pioneer. I was an animal care technician. So I also performed a lot of euthanasia. I just knew something had to change.

But I’ve also had a lot of help along the way. A lot of help. Not just from the League’s team and our board, but people from around the country have always been willing to share with me. I joined SAWA (Society of Animal Welfare Administrators) in 1978. When SAWA was a very small organization, there were guys who were my senior by 20 years, 30 years, who were willing to talk to me. I’ve had a blessed career, but I didn’t ever do anything by myself.

Do you have any advice for young sheltering professionals?

Number one, working together works. The more groups that you can work with the better. I’m not saying it’s going to be easy, but we all want the same thing: healthy pets in forever homes. We all want that, whether it’s the veterinary community, whether it’s the sheltering community, whoever it is. So let’s work together to make it happen.