Blog: Making the most of TNR

What conservationists and community cat advocates learned from population modeling

April 6, 2022

A biologist dedicated to bird conservation, another focused on endangered species, and a veterinarian devoted to trap-neuter-return walk into a bar …

Wait, scratch that. They walk into a conference room—but cocktails are involved.

The meeting includes John Boone with the Great Basin Bird Observatory, Phil Miller with the Conservation Planning Specialist Group and Dr. Julie Levy of Operation Catnip, plus several other experts. They’re all part of a think tank on the use of population models to develop more effective and efficient sterilization strategies for free-roaming cats.

The meeting leads to the formation of a 10-person committee, organized by the Alliance for Contraception in Cats & Dogs (ACC&D), to develop the models. Among the committee members are veterinarians, modeling experts, animal welfare professionals and wildlife economists, all collaborating across disciplines and perspectives on outdoor cats.

Everyone respects one another, and the different perspectives that members bring to the table strengthen rather than diminish the work. Most of all, everyone wants information that can help guide data-driven decisions about free-roaming cats.

Fast-forward to today: The group, which I’m member of, has published three peer-reviewed journal articles: the first on initial population modeling results, the second on preventable cat deaths, and the third on how to balance population impact and cost in free-roaming cat management. There’s also a companion guide for those who want practical takeaways from all this modeling without the extensive technical stuff, and we’ll soon publish a guide to help folks effectively monitor outdoor cat populations and quantify their success.

Why did we decide to apply population modeling to free-roaming cats? Because despite the increasing popularity of TNR in recent decades, there’s still little real-world data to help advocates choose the best approach for their sterilization projects.

Despite the increasing popularity of TNR in recent decades, there’s still little real-world data to help advocates choose the best approach for their sterilization projects.

Population modeling, which has long been used in wildlife biology and other fields, offered the next best option: Using what real-world data exists, adding expert input where needed and simulating the effects of different TNR approaches using a realistic computer model. In this way, we were able to simulate the long-term impacts of 14 different management strategies for reducing community cat populations, including TNR, trap and remove, episodic culling and a combination of approaches—each performed at high, medium and low intensities—and no action.

The great news is that, over a 10-year period, the models showed that TNR can be a cost-effective way to reduce free-roaming cat populations. However, the models also showed that we need to perform TNR in specific ways to achieve this result.

Here are some key takeaways.

Identify your target and your goals. Before beginning a TNR project, identify your target population and set clear goals for what you want to achieve. The best approach will depend, in part, on your goals. Do you want to reduce population numbers? To completely eliminate a population in a particular area? To reduce nuisance complaints?

If the goal is to eliminate a population of cats, removal (lethal or nonlethal) will be more effective than TNR for obvious reasons: The cats are taken away. However, the number of cats who would need to be killed is so vast, and the need for killing so relentless (especially with abandonment and immigration factored in), that it won’t be acceptable or feasible in most communities.

Count first. To evaluate the effectiveness of your efforts, you need to measure the baseline number of cats in your target area, determine where they’re located, and continue to monitor changes as you work to manage the population. (ACC&D has resources on how to do this; the DC Cat Count provides detailed guidance, as well.)

“Front-load” your efforts. Front-loading your TNR efforts means sterilizing 75% of intact cats very quickly—even if it requires investing extra resources at the start or focusing on a smaller area. (You can later fan out to cover more ground.) Once done, make sure that the proportion of sterilized cats never drops below 75%; ideally, it will become progressively higher. We can’t emphasize enough how important this high-intensity TNR is to achieving good results (population- and cost-wise) over 10 years!

Curb immigration and abandonment. The arrival of new intact cats can really sabotage progress. Our modeling showed that adding just one new cat to the target population every six months more than doubles the cost of achieving the same population reduction compared to no added cats. Fundamentally, an overabundance of free-roaming cats is as much a “people problem” as it is a “cat problem.” When possible, you might also focus TNR efforts in more isolated areas with barriers that prevent the introduction of new cats, such as a river or highway.

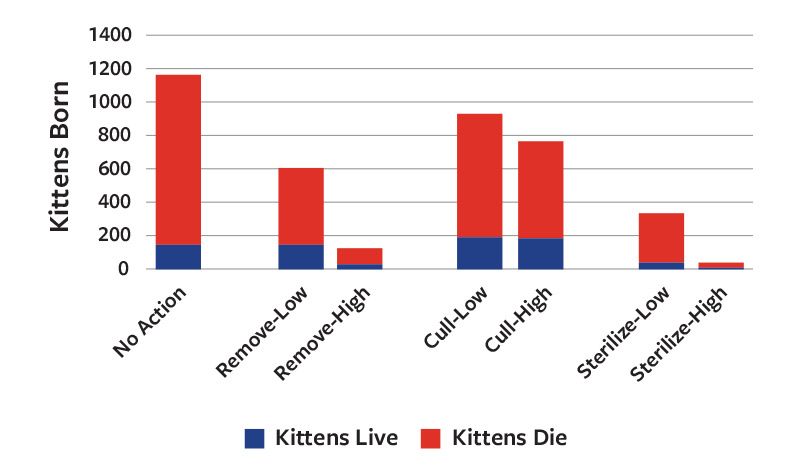

Don’t ignore preventable deaths. When we accounted for preventable deaths (the high mortality of kittens born outdoors plus any cats killed to manage populations), the lifesaving impact of high-intensity TNR was much greater than other scenarios we modeled. Focusing on the deaths that don’t occur requires a shift in thinking, but it’s oh-so-important when your goals are to minimize suffering and maximize lifesaving.

We hope our findings inspire TNR groups to take a close look at ways to make their work more effective, both in terms of reducing populations and using limited resources efficiently. We also hope funders will think about how they can better support groups to front-load TNR efforts and reduce abandonment and immigration of new cats.

Of course, the models are just that: models. We can’t guarantee that they will always match real-world outcomes. However, what we developed was based on every bit of field data that the committee could access and expert opinions when data wasn’t available.

Several members of ACC&D’s modeling committee were deeply involved in the groundbreaking DC Cat Count, and ACC&D staff participated in all eight years of the Hayden Island (Oregon) Cat Count, which generated estimates of the number of cats on the island over nearly a decade. The modeling also helped inspire field projects to monitor free-roaming cat populations, whose data can in turn help to refine future models.

ACC&D’s modeling work, as well as the cat counting projects that followed, is a testament to the fact that, contrary to how the media often portrays relationships among wildlife, bird and cat advocates, there’s ample ground to collaborate in ways that can benefit all species.