Blog: Take a stand against feline toe amputation

Declawing doesn’t keep cats in homes and hurts much more than their paws

March 2, 2022

I’ve met a lot of cats during my 20-plus years in animal welfare. But a handful of them stand out for the bigger stories they tell.

One of these was Secret Agent Kitty, who crossed my path when I was managing the community cats program at an animal shelter. He was a stray found by a kind passerby and brought to the shelter for assistance.

While Secret Agent Kitty was healthy and handsome, he didn’t appear to be a good adoption candidate. He’d hiss and swat at anyone who looked at him the wrong way, let alone tried to touch him, behavior that—at the time—could quickly earn a cat the “feral” label. He was a big orange kitty, the kind I have a soft spot for, and since he couldn’t be neutered and returned to the location he was found, I pledged to find him an alternative home.

The first time we could really get our hands on him was when he was anesthetized for neutering. That’s when his story changed. He was already neutered—and he was declawed. Suddenly, it all made sense. He wasn’t being aggressive. He was scared. Cats are both predator and prey, and this one had been stripped of his natural defenses. After 24 hours in a quiet foster home, Secret Agent Kitty embraced a new identity—lap cat—and shortly thereafter moved to a permanent assignment.

Since my time working at the shelter was focused on community cats, you wouldn’t think declawing would have come up much. But my team and I found more declawed cats outside than you’d think if you were unaware of the problems that declawing can cause. The same kind of problems that can lead to a cat being evicted from their home, like not using the litter box or biting people.

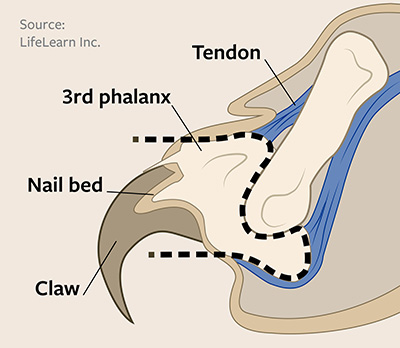

Litter box aversion is more common in declawed cats—and for good reason. Cats walk on their toes, and when those toes are amputated, digging in rough cat litter can hurt. Walking can hurt. Cats can experience phantom pain from the amputations, pain from bone fragments left behind or pain from arthritis caused by having to change the way they walk.

Most people I know who have had declawed cats either adopted them from the shelter already clawless or got them declawed before they knew better (also known as before the internet). In my circles, declawing is rare, but pet owner surveys over the years show a steady 20% of owned cats are declawed. That’s a lot of cats.

Amputation is an extreme response to what can be addressed with regular nail trimming, a variety of scratching posts and a better understanding of feline behavior. Fortunately, the U.S. veterinary community is increasingly aware of this and increasingly opposed to declawing, thanks to pioneering work by The Paw Project and Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association. Yet veterinary trade organizations push a false narrative that without the option to declaw and prevent unwanted scratching of either furniture or people, owners would relinquish their pets to animal shelters, thus putting those cats at risk of euthanasia.

It might be a persuasive argument if it were true, but there’s no evidence to support it. Plus, the story that’s being told makes shelters out to be the bad guy, to be a fate worse for a cat than having their toes amputated.

My team and I found more declawed cats outside than you’d think if you were unaware of the problems that declawing can cause. The same kind of problems that can lead to a cat being evicted from their home, like not using the litter box or biting people.

In reality, shelters where declaw bans have been enacted haven’t seen an increase in cats surrendered due to the ban. In a recently published study, researchers analyzed data from shelters across British Columbia, Canada, for the three years before a provincial declaw ban was enacted and the three years after the ban. There was no increase in cat intake, owner-surrendered cats or cats relinquished for destructive behavior. There was no increase in cats being euthanized or even in feline length of stay.

The shelter and rescue community can play a role in the demise of declawing by sharing the truth about clawless cats who end up in their care. What aftereffects of toe amputation do you see? How are you changing potential adopters’ minds about declawing their new feline friend? Let’s tell the real story and take a stand together against this inhumane practice.

Join us in support of laws to prohibit nontherapeutic declawing. If you represent a shelter or rescue, please sign our declaw ban support statement. If you’re a veterinarian, veterinary technician/nurse or veterinary medical student, please sign HSVMA’s support statement.