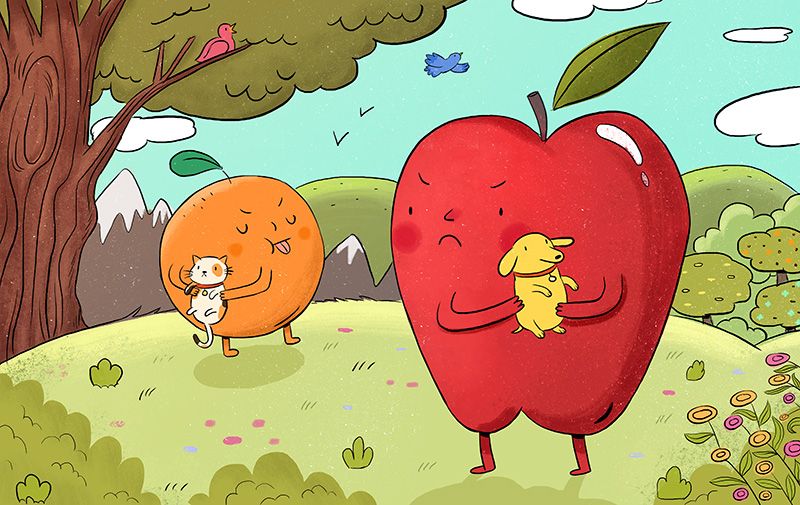

Apples and oranges

When organizations are at odds with their volunteers, a fruitful outcome requires a firm hand

The volunteer just couldn’t stop spooning the dogs.

“She was very invested,” says Hilary Hager, recalling the woman’s affection for the animals at the shelter.

Hager, who has managed volunteers for two shelters and is now director of volunteer engagement at The HSUS, says the volunteer worked at her former shelter five days a week. Once, staff had found her walking barefoot in the kennels. Later, she kept lying on the floor of the kennels, cuddling the dogs.

Several times, Hager explained that spooning was not part of their approved animal handling protocol—or any animal handling protocol—but the volunteer couldn’t resist. She couldn’t guarantee that she wouldn’t cuddle the dogs. And so Hager thanked her for her honesty and let her know she wasn’t a good fit for the organization.

Some volunteers substitute their own preferences for the rules, says Hager. From playing the big spoon to sneaking forbidden treats into the kennels, flouting the rules doesn’t mean a volunteer is a bad person—but it does mean she may need some guidance, or a gentle push out the door, to ensure she’s not derailing your organization’s programs.

Sometimes, wayward volunteers simply don’t understand the reasoning behind protocols they see as arbitrary, and a little information can provide a quick fix. Other times, volunteers are just not able or willing to help the organization in the way the organization wants to be helped.

Hager has spent her career developing systems and techniques that empower organizations to harness the great energy and passion of volunteers, who are critical to the work of countless nonprofits.

Yet they “can be the best of times and also the worst of times,” she notes, riffing on literary classic A Tale of Two Cities to describe her experiences. “I really do love volunteers,” she says. “But often there’s tension between organizations who need help and the people who want to help.”

Why Us?

Tensions within staff-volunteer relationships aren’t unusual, but they may be particularly strong in the animal welfare industry.

“Many people in animal welfare tend to see conflicts as literally life or death,” says Karen Green, executive director at the felines-only Cat Adoption Team shelter in Sherwood, Ore., and author of Conflict Resolution for the Animal Welfare Field.

Green pursued a B.A. in organizational communication after working in animal welfare for 10 years. As her capstone degree project in 2009, she surveyed paid employees as well as volunteers to measure the impact of conflict on animal welfare organizations.

At shelters and rescues, “so frequently conflicts [are] destructive conflicts,” she says. “It interferes with the organizations’ ability to save lives.”

Green found that only 18.2 percent of employees and 25.5 percent of volunteers could report that conflict had not affected their work satisfaction; perhaps more tellingly, 24.5 percent of employees and 40.6 percent of volunteers had left a position at a previous animal welfare organization because of conflict.

Hager says the reasons for this are myriad. Animal welfare work is a “highly emotionally charged environment anyway,” and the emotions affect everyone, from volunteers cycling in and out of the organization, to the people who have committed their lives to working with animals, to the animals themselves, who are often stressed.

What’s more, people often “self-select” to work with animals because they prefer animals to people, she says, and they don’t realize that animal welfare work requires strong interpersonal skills. When people who don’t have good people skills work with lots of other such people in an emotionally charged environment, conflict is “sort of inevitable.”

Averting Disaster

There’s a difference between a problem person and a problem workplace, however, especially if your organization is having issues with more than one volunteer. Ever heard the saying, “If you meet three [jerks] in a day, you’re the [jerk]”? Ensure your organization isn’t acting like a jerk—if you give people the tools they need to be great volunteers, you might be surprised by how much your jerk census is reduced.

Ollie Davidson, programs director at Tree House Humane Society in Chicago, oversees more than 400 volunteers in two locations. He recommends that organizations start prospective volunteers with a mandatory orientation that serves as an “infomercial” for your organization. It should be informative and make people feel positive about your mission, whether or not they choose to volunteer. Once volunteers have completed the orientation, they should move on to structured training sessions.

People want to know that “the place where they’re donating their time aligns with their values and is a place where they want to work,” says Hager, “so the more transparent we can be up front about who we are, what things are like and what we’re looking for,” the better your volunteer outcomes will be.

Be direct about the volunteer roles you need, and provide a job description, application and waiver, a workplace culture agreement and an essential capabilities document (stipulating the basic physical and mental capacities required—for example, “Must be able to lift up to 10 pounds without assistance”), just as you would for a paid position. Include clear protocols for tasks the volunteer would take on, such as feeding or scooping litter. Most importantly, be “crystal clear” about off-limits tasks, says Hager, like euthanasia decisions.

Davidson receives 30-50 volunteer applications a week. Tree House relies heavily on volunteers but previously had issues with staffers mistrusting volunteers’ training and knowledge; in 2015, the organization implemented a new procedure to help staffers and volunteers work together as a team.

“Volunteers and staff [go] through the exact same training,” says Davidson. “Everybody is on the same footing as far as what our mission is, what our protocols are [and] why we have the little idiosyncrasies that we have.”

The training has several levels, including a “Tree House 101” that goes over the nitty gritty of job duties and provides an overview of how to handle common situations.

Personal interaction—asking people to introduce themselves and share why they want to volunteer, for example—is built into each training to help gauge people’s personalities and expectations. Hager also suggests catering to diverse learning styles with lectures, readings and shadowing of established volunteers.

At the end of the training process, Hager recommends meeting each volunteer and taking feedback from volunteer trainers, confirming each person is a good fit before you make her volunteer role official.

At Tree House, a certification program allows volunteers to take on different roles with gradually increased responsibilities. People start at a “basic” volunteering level and work up from there. (If your organization needs volunteers to dig right in, try assigning volunteers to experienced mentors before letting them go it on their own.)

The certification program “gives [volunteers] a path and an expectation level ... it gives them a sense that this is something we take very seriously, and that they’re going to be part of the organization [and] we’re looking for them to buy in and follow through,” says Davidson.

“There are always going to be personality differences,” he adds, but having team members who are dedicated liaisons between staff and volunteers can help keep problems impersonal and provide a clear path for handling issues.

All staffers should be trained on how to respectfully and confidently intervene if a volunteer isn’t following protocol, says Hager—even following a straightforward script if they’re initially uncomfortable. Clear rules and quick and consistent correction prevent a “gotcha” situation later, where volunteers may feel like staffers were just waiting for them to mess up.

Don’t worry about deterring potential volunteers, says Hager. “Most people really do appreciate structure and consistency and understanding the process,” she says. If someone complains that, “Ooh, I don’t like structure, I don’t like people telling me to do things,” then that’s revealing.

Picky, Picky

You might desperately need volunteers, but don’t accept just anyone, says Hager, because bad-fit volunteers can only worsen an already chaotic situation. It isn’t as difficult as you might think to identify potential problem volunteers during orientation and training.

For example, a potential volunteer who says, “I want to volunteer because I love animals and I hate people,” would likely have difficulties interacting with you, your staff, other volunteers and adopters—who are all people.

People who only want to rub puppy bellies all day are going to be sorely disappointed; people who question shelter methodology or announce their own expertise (Davidson calls these people “faux experts”) are likely to change your crafted protocol for what they think is best; people who make disparaging or negative comments at the outset probably won’t get any happier as time goes on.

There’s no need to seek out bad-fit volunteers after training, says Davidson. “We always try to minimize our conflict … we wouldn’t directly reach out to them first without them reaching out to us for the next step,” he says. If a volunteer already senses they’re not a good fit, they’ll often choose on their own to not continue training.

If an iffy volunteer persists, don’t be afraid to say, “We don’t have a good [position] for you right now, but we’ll keep you in mind,” says Davidson, or give volunteers a “heads up” that they might be happier at a different organization that’s more in line with their values or expectations.

Remember that even people who aren’t a good fit for your organization’s in-house needs could help in other ways. If you keep bridges intact by treating people respectfully, failed or nonstarter volunteers might advocate for your organization in the community or become adopters, foster caregivers or donors in the future.

Even if you’re telling a potential volunteer that you don’t have a place for him or asking a current volunteer to leave, “make them walk away feeling good,” says Davidson, and “be empathetic and appreciative of the help they’ve offered.” Not only is it kind, but also best for your organization’s reputation.

Working It Out

Say despite your best preventive efforts, you’ve got yourself a rogue volunteer. “Everyone Ready: Handling Challenging Behavior by Volunteers,” a training seminar led by Steve McCurley, suggests striving for a full, objective understanding of the situation. Clearly identify the issue, how it affects others and potential causes.

Don’t forget to “check your intentions,” says Green. “Often, people act as though they want to resolve a conflict when what they really want is to prove that they’re right,” she says. “The other party has valid interests that are as important to address as our own.”

It’s essential not to avoid difficult conversations, which can frustrate staffers and “demoralize” other volunteers, says McCurley. Once you have a fair picture of the problem, immediately set aside a time and neutral place to discuss the issue privately with the volunteer.

At the meeting, state the problem and how it affects others. Focus on “interests” (what you and the volunteer need) rather than “positions” (what you and the volunteer have already decided must happen for your needs to be met), says Green. Ask the volunteer for her point of view—and listen to her response.

“What we often call listening is simply waiting until it’s our turn to talk,” says Green. “You can make a huge impact on your conflict communication by making a sincere and consistent effort to really understand what the other party is trying to tell you.” Ask, “Is there anything about the work itself that’s interfering with your ability to do the job?” or “Was there a specific incident that upset you?”

If the volunteer is receptive, McCurley says you can move on to “mutual problem solving”: an agreement that a problem exists and a discussion of the volunteer’s ideas about how both she and the organization can get what they need. Ask, “What do you think others can do to modify the situation?” and “What could you personally do to improve the situation?”

The volunteer job description and workplace culture agreement can come in handy here, because—if written appropriately—they will document the agreed-on tasks and behavior and can serve to contrast with the volunteer’s current work and behavior.

McCurley suggests choosing a “re” solution: re-supervise the volunteer to ensure rules are being followed, reassign her to a new role, retrain her, revitalize her by assigning her to a less emotionally challenging role or offering her a sabbatical, refer her to a better-fit organization or, finally, retire her with dignity.

Letting Go

“It’s really best in that situation to make it quick,” Davidson says of “retiring” a volunteer. “It’s a difficult conversation, I don’t enjoy it … but if you don’t deal with it right away, other staff members and other volunteers will see this problem happening and have this person working with them. The rest of the program is going to suffer.”

While you always hope that the volunteer will be able to meet your organization’s needs, says Hager, “if the volunteer is making work more difficult, it’s time to part ways.”

“Retention is an outcome” of good volunteer management, she says, “not a task.” If you must ask a volunteer to leave, take it as an opportunity to assess your volunteer recruitment and management, not a failure.

Stay measured, calm and positive during the conversation, and be nonjudgmental but specific about why—is it for the health and safety of the animals? Was the issue affecting customer service or other volunteers?

Remember that retiring a volunteer is not a condemnation of the volunteer or the organization, says McCurley. You’re breaking up, and like any breakup, sometimes things just didn’t work out.

“Ultimately, people want to be of service,” says Hager. By letting a bad-fit volunteer move on, you’re giving her the opportunity to be of service—somewhere else, where she’s a better fit.