Viral shift

New research is revolutionizing how shelters view feline retroviruses

In shelter medicine circles, Jasper—aka Jasper the Jerk—is a bit of a celebrity.

Intolerant of other cats, full of energy, and happy to destroy furniture and other household objects, the Maine Coon-type cat has been adopted and returned four times over the past six years.

But it’s what is circulating inside this 15-pound bundle of cattitude that has baffled researchers and shelter staff alike. Because Jasper’s body consistently defies what everyone thought they knew about the feline leukemia virus.

“His bloodwork changes from month to month and from test to test,” says Monica Frenden, director of feline lifesaving at American Pets Alive!, the educational offshoot of the Austin Pets Alive! shelter in Texas. “We’ve all been told that the IFA [immunofluorescent antibody] is the definitive test for feline leukemia, but Jasper will be IFA’ing negative for four consecutive months and then test positive.”

In recent years, Jasper has been the subject of numerous conference calls among feline health experts; his blood has been sent to researchers around the U.S. and Scotland so that they can run their own tests—and rerun them, and rerun them again.

So will Jasper live a long, healthy life or eventually succumb to the virus? No one can say for sure.

But he isn’t a rare outlier. In ongoing studies of FeLV cats adopted from the Austin shelter, more than a quarter have been labeled “discordant,” meaning their monthly blood tests repeatedly show contradictory results.

The impetus for the research began in 2011, when the shelter launched an adoption program for cats who had tested positive for the virus. To allay adopters’ concerns over future medical costs, the shelter offered free lifelong veterinary care for virus-related illnesses at its in-house clinic. “We started noticing years and years ago that these cats we were all told were going to lead short lives were not dying,” Frenden says.

As adoption numbers grew, the shelter’s leaders realized they had a unique data set—and an opportunity to learn more about feline leukemia and how it affects individual cats.

There are still plenty of unanswered questions. But these studies and others are changing how the sheltering field views feline retroviruses, and they’re having real-world impacts on adoption policies, housing and testing protocols.

“Back in the day, a positive test ... was automatic euthanasia. There were no resources for extra testing.”

—Dr. Erica Schumacher, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine

A tale of two viruses

If there’s one lesson the entire world learned in an unforgettable way this year, it’s that viruses are mysterious, unpredictable and can affect individual carriers in widely different ways.

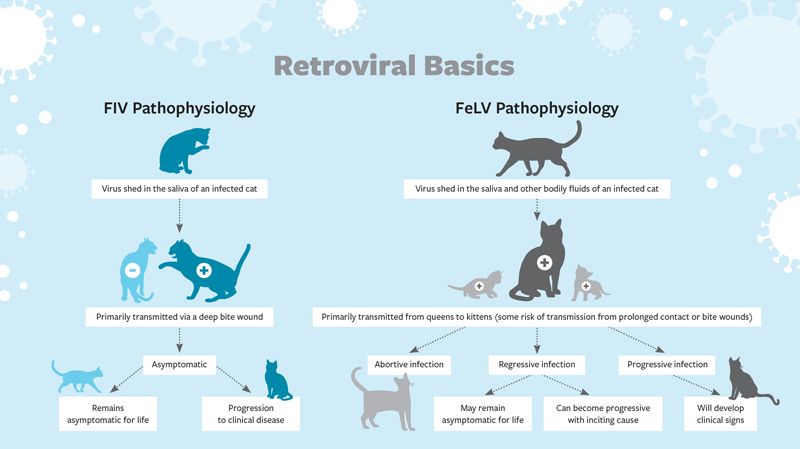

Those basic truths also apply to feline leukemia and feline immunodeficiency virus. Classified as feline-specific retroviruses (which means they’re RNA-based and only infect felines), FeLV and FIV affect roughly 2-5% of cats in the U.S.

For decades, these viruses were considered a death sentence for cats. And in a shelter environment, they typically were, says Dr. Erica Schumacher, outreach veterinarian with the Shelter Medicine Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine. In 2003, when Schumacher started working at Dane County Humane Society as a veterinary technician, “a positive test, whether it was feline leukemia or FIV, was automatic euthanasia. There were no resources for extra testing. There was no space to hold them for retesting. When euthanasia decisions were being made on multiple animals every day, it seemed to be a straightforward choice.”

Five years later, the shelter started making FIV cats available for adoption and discovered that some people weren’t deterred by a cat’s positive status, says Schumacher. “Fast forward to now: FIV and FeLV cats are made available for adoption with information about both diseases.”

Many shelters around the country have experienced a similar shift, partly because of an increased understanding of the viruses, and partly as a result of our field’s success in reducing shelter intake numbers. As Frenden puts it, “when healthy kittens were being [euthanized] by the bushel, of course I couldn’t save the sick FeLV-positive cat. … We’re coming along as a society.”

But progress hasn’t been uniform, and misinformation and myths surrounding FIV and FeLV still persist. “A lot of people have outdated information,” says Dr. Emily Swiniarski, chief medical officer at PAWS Chicago.

One common misperception is that FIV and FeLV are highly contagious. In reality, they don’t survive for long outside their feline host. The viruses are “killed by the most basic of cleaners,” Frenden says. “They’re not panleukopenia or parvo,” which is why shelters don’t experience outbreaks of FIV and FeLV like they do with these hardier viruses.

When using an FIV/FeLV test to aid with decision making for sick cats, “interpret the results in consult with a veterinarian familiar with the current understanding of testing and disease course.”

—Dr. Cynthia Karsten, UC-Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program

Even among cohabitating cats, FIV and FeLV are harder to transmit than researchers once believed.

FIV is primarily transmitted through deep bite wounds, when the virus enters the bloodstream of the cat. Unsurprisingly, unneutered free-roaming toms, who are the most likely to fight over territory and mates, have the highest incidence.

In a study published in 2014, researchers followed a group of 130 FIV-negative cats and eight FIV-positive cats, all of whom were sterilized and mingled freely in a rescue environment. After several years, despite mutual grooming and “minor episodes of aggression,” none of the negative cats tested positive.

FeLV, which is found in the blood, saliva and other bodily fluids of an infected cat, is most commonly transmitted from an infected queen to her kittens. Healthy adult cats have partially protective natural immunity to the virus, says Dr. Julie Levy, professor of shelter medicine at the University of Florida—but there is a small risk of spread through casual contact, such as mutual grooming or sharing water and food bowls.

While there are plenty of anecdotal reports of noninfected cats cohabitating with FeLV-positive cats without contracting the virus, most experts recommend not mixing the two populations. At the same time, Frenden points out, “it’s uncommon to transmit FeLV in sterilized adult cats. It takes prolonged intimate contact, and even then it’s uncommon. Cats housed next to each other in cages are not going to give FeLV to one another, even if they sneeze on the other.”

Some of this information isn’t new—studies as far back as the 1970s (for FeLV) and late 1980s (for FIV) showed the diseases aren’t easily transmitted among sterilized cats. But in 2002, when Dr. Aleisha Swartz graduated from veterinary school, “my understanding was that we would actually be able to test every cat and stop this disease in its tracks.” While eradicating these viruses across the globe is a “noble idea,” adds Swartz, who is chief of service with the Shelter Medicine Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, “the reality is that such a small fraction of cats are ever brought into a shelter or veterinary hospital, and even fewer are tested. And the testing itself is more complicated than originally hoped. The good news is that the primary routes of transmission are effectively blocked by sterilization.”

But the idea that euthanizing infected cats can eradicate the viruses has lingered. Until last year, Kansas law prohibited shelters from adopting or transferring cats who tested positive for either disease. New Hampshire had a similar law until 2017.

Nasty, brutish and short?

Another widespread myth about retroviruses is that cats who test positive are fated to live short, illness- plagued lives. That’s what Swartz was taught in veterinary school, but while working in private practice, she met many living refutations of this dogma. She remembers an orange-and-white cat named Cinnamon, who as a kitten had tested positive for FeLV. His owner said to her, “Every vet told me this kitten was going to die at a very young age, but he never got the message.” Cinnamon was about 10 years old and thriving.

“There were multiple stories like that, just in my teeny tiny sliver of practice life,” Swartz says. “How many of those are out there, and how many of them could be out there but because given that information that they’re going to die, and be sick, and it’s going to be a terrible life, a recommendation is made and the owners opt to euthanize them?”

Several studies show that FIV cats have comparable life spans to noninfected cats, but the answer for FeLV cats is more complicated. “We have no idea how long naturally infected cats with FeLV live … because historically our industry has always euthanized them,” Frenden says.

The data so far indicates a significantly shorter than average life expectancy, but with tremendous variability among individual cats. Some cats who initially test positive will essentially buck off the infection (an “abortive” infection) and later test negative. Some, showing what’s called a “regressive” infection, will continue to test positive with low levels of virus but could remain healthy into their teens and 20s. Some will have a “progressive” infection and succumb to a virus-related illness at an early age. And then there are the “discordant” cats like Jasper, whose test results flip flop from month to month.

What causes an individual cat to go down a certain pathway is yet unknown.

American Pets Alive! is three years into what could be a 20-year study on FeLV that researchers hope will provide the answers. For the first six months, the group sent vials of blood to IDEXX Laboratories in Maine and to the University of Glasgow in Scotland, where FeLV was first identified in the 1960s. “They’re running extremely eloquent research on the blood we send in … basically looking at it on a cellular and DNA level, trying to figure out why some cats respond so much better to the virus,” Frenden says. The ultimate goal is to identify the most reliable tests and whether there’s a trigger that can be manipulated to either eradicate the virus or prevent cats from moving into the progressive stage.

One of the biggest discoveries so far, Levy says, is “that we identified a new test that could be used to determine if cats were likely to be in a regressive state versus a progressive state. As a group, cats with regressive infections had a slightly shorter life span then uninfected cats, but they lived much longer than cats with progressive infection.”

When it comes to FIV/FeLV testing, “no test is perfect, and there is tons of room for human error, too.”

—Dr. Julie Levy, University of Florida

Still, when it comes to predicting how long an individual cat will live, there’s no clear-cut answer. “All I can tell you is what a positive test result doesn’t mean,” Frenden says, “and right now we know it doesn’t mean that it’s a fatal lifelong virus that is definitely going to kill your cat.”

And just as shelters have discovered that some people are happy to adopt senior, fospice or other special-needs pets, there are those willing to take a chance on FIV and FeLV cats. A recent study by American Pets Alive! and Maddie’s Fund surveyed adopters of FeLV cats and found that not only were the cats healthier than the adopters expected, but that “our leukemia adopters were more attached to their cats than our control population,” Frenden says. “They would come right back and get another feluk cat.”

“We call it ‘FeLVie fever,’” she adds. “They become fierce advocates” for this population of cats.

Under the microscope

A disconcerting finding from recent studies on feline retroviruses is this: The tests long used to make life-or-death decisions about individual cats aren’t as accurate as we’ve believed.

This is partially due to the fact that testing a large healthy population for an uncommon disease may result in a significant number of false positives. It’s a problem the human medical field also grapples with, leading to controversy over the value of practices like routine blood tests for prostate cancer.

One of the most trusted FIV/FeLV point-of-care tests (the type commonly used in shelters and veterinary clinics) has a 98% accuracy rate, which sounds pretty good—until you look at how that plays out in real life. If you test 1,000 random cats with no signs of virus-related illness for a disease with a 3% prevalence, 49 cats will test positive, Schumacher says. Of those, 20 will be false positives.

And that’s assuming the most accurate POC test is used: A study looking at four brands found that for three of them, up to 76% of FeLV positive results would be false.

Tests can also miss regressive FeLV infections (a false negative result), and they’ll miss recently acquired infections still incubating in the cat’s body.

“It makes interpreting the test and examining your results so darn confusing,” says Dr. Cynthia Karsten, outreach veterinarian at the University of California-Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program. “It can be very difficult to be 100% sure.”

Faced with these uncertainties, many shelters are questioning whether testing cats who show no signs of a related illness is a good use of resources.

Along with the cost of the test kits, routine testing is “a very large time commitment for shelters, not just drawing the blood and running the tests, but only having so many people who are able to do it,” Karsten says. “So you have animals who are waiting, and it can have quite an effect on length-of-stay, crowding and illness. And then you get the results, and you have to do something with them. And then not fully understanding them, or simply repeat testing a cat until you get a negative.”

On top of all this, you have all the ways in which human error—in how tests are stored, used and interpreted—can skew results. And the tests can’t tell you which cats will become sick or die young because of the virus.

“I think the tests can give you a false sense of security,” Swiniarski says. “There are so many other interventions that contribute to health that are worth your time and effort.”

Examining the big picture

That was the conclusion Levy came to in the 1990s, a few years after she founded Operation Catnip, a high-volume trap-neuter-return program for community cats. “We looked at the amount of money we spent and realized we could do more for cats if we discontinued testing,” she says. “We made a strategic decision that we would always focus on how to spay and neuter more cats. Fortunately, sterilization also addresses the two main ways these viruses are spread—birth of susceptible kittens and fighting.”

Twenty years later, Levy is seeing more organizations apply the same thought process to shelter cat populations. It’s a question of “how do we leverage our finite resources to help the most cats?” Levy says.

Because of its ongoing research on feline leukemia, Austin Pets Alive! still tests every cat for FeLV, but last year the shelter stopped routine testing for FIV, resulting in an annual savings of about $33,000. “If someone handed me a check for $33,000 to save the most cats I could, I wouldn’t spend it on FIV testing,” Frenden says.

Instead, the decision about whether and when to test a cat who appears healthy can be made by the adopter in consultation with their veterinarian, Karsten says. To that end, American Pets Alive! is working with test kit manufacturer IDEXX to create an educational toolkit for private practice veterinarians.

“There are still plenty of people who believe these cats are sick and suffering and so they should be euthanized,” Frenden says. “So we’ve realized we have a lot of work to do to bring all the industry, not just the shelter industry, up to current research.”

“A question we encourage every veterinarian and shelter to ask before committing resources to diagnostic testing is: Will the test result change their course of action?” Swartz says. “Will running a test improve treatment, reduce the risk to other animals, or allow them to implement a more effective intervention to stop transmission? Because there’s no specific medical treatment for FeLV or FIV, the viruses aren’t persistent in the environment, and the most common routes of transmission are avoided with sterilization and good husbandry, it’s hard to justify the use of finite resources to test every healthy cat and kitten in shelters.”

Those resources could be better directed to implementing a shelter-neuter-return program and improving housing to reduce cats’ stress and support their immune systems, Swartz says. “If there are fewer cats who are less stressed, they’re less likely to be exposed to and susceptible to a variety of infectious diseases.” When it comes to group housing, “we also know we can mitigate risks by having smaller groups where it is easier to ensure compatibility and better monitor to prevent fighting.”

“Be ready to discuss the fact that, no, FIV does not spread easily between cats; FeLV is hard to spread; we don’t test, and here’s why.”

—Dr. Emily Swiniarski, PAWS Chicago

As a new understanding of feline retroviruses takes hold, shelters that have discontinued routine testing are helping to allay fears among other organizations that might be considering a similar change. “One of the myths in animal welfare, every time we talk about switching to not testing, is that the [general public] is going to panic,” Swiniarski says. “The truth is that the vast majority have no idea what this testing means.”

At the same time, she adds, shelters should have “up-to-date information to provide to any other organization or even veterinarians that would like to discuss it. Be ready to discuss the fact that, no, FIV does not spread easily between cats; FeLV is hard to spread; we don’t test, and here’s why.”

A few years ago, when Schumacher worked at the Dane County Humane Society in Wisconsin, the shelter was spending about $50,000 a year to combo-test every cat. “Initially, the shelter looked at removing testing for financial reasons, then it was the relatively new understanding that the tests weren’t giving us the information that we thought they were,” she says. “That was the bigger reason to stop [routine] testing in the shelter.”

Not everyone agreed with the decision. “I did have a couple of vets reach out to me and say, ‘Are you crazy? What are you doing?’ For me, once I learned about how much we didn’t know about the tests and that we couldn’t trust the results as much as we thought we could, it became kind of a no-brainer to me. Once you learn the facts, it’s not difficult to change your mind.”

And as new facts come to light, our understanding of feline retroviruses continues to evolve at a rapid pace, Frenden says.

“Keep reading and learning,” Schumacher advises. “What you read or learned five years ago or one year ago may be different today.”

Document