Career spotlight: Community cat coordinators

Shelters are discovering the multiple benefits of hiring staff focused on outdoor cats

The road to Angéline Fahey’s current career started with two skittish cats living outside her apartment complex in Tucson, Arizona.

Fahey began feeding Goose and Hunter in the summer of 2020 and, while looking for a way to get them sterilized and vaccinated, stumbled across a job posting for a cat trapper at the Humane Society of Southern Arizona.

Fahey had spent much of her childhood in a remote village in the French Alps where outdoors cats abounded. She loved cats, but she’d never trapped one or contemplated a feline-focused career.

Her first day on the job, she learned how to lure wary kitties into box traps. By the end of the second week, she was trapping on her own, and Goose and Hunter were headed to the spay/neuter clinic. Fahey was hooked.

Today, as community cat coordinator for the HSSA, Fahey leads a group of three paid trappers and about 40 volunteers, all focused on using trap-neuter-return to improve the lives of outdoor cats and reduce shelter intakes.

On any given workday, Fahey is talking to people who are fiercely protective of the outdoor cats they feed—and people who want her to make those same cats magically disappear. She’s meeting with property managers, scheduling spay/neuter appointments and organizing group trapping projects. She’s discussing cases with her shelter’s animal services officers, front desk staff, medical team and foster care coordinators. In between, she may be preparing a presentation for a homeowner association, writing a newsletter for a local community cat coalition, or tackling some other task on what she describes as “a to-do list that never seems to go down.”

With a service area that includes all of Pima and Cochise counties—home to almost 1.2 million people—the need can feel overwhelming, Fahey admits. But she’s making a tangible difference in her community, and her job is never boring. Last year, her team trapped nearly 3,000 community cats for sterilization. They facilitated spay/neuter for hundreds more by loaning equipment and providing guidance to cat caretakers all over the state.

“Every cat you trap, every person you help, is an improvement,” Fahey says.

From grassroots to mainstream

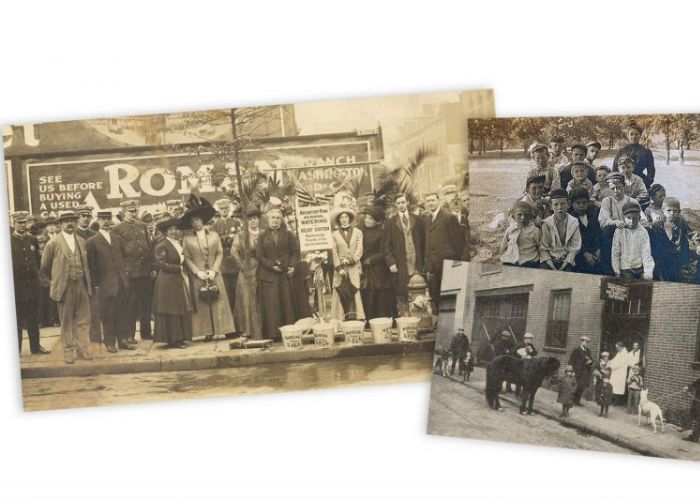

In 2012, when Danielle Bays was hired to manage a citywide TNR program for a Washington, D.C., animal shelter, her position was a rarity. Few shelters had staff dedicated to community cat management, says Bays, who currently works as senior analyst for cat protection and policy at the Humane Society of the United States.

That’s changed over the years as more shelters strive to tackle the roots of feline overpopulation and bring animal care services to areas of need. “When we talk to shelters about their biggest challenges, often it’s cats, particularly community cats,” says Bays. “It’s really hard to address that challenge without having a dedicated staff position.”

With a staffer leading the way, shelters can bring a higher level of intensity to community cat management. They’re able to respond more quickly to calls for assistance, address complaints and ensure that policies and protocols are accurately communicated to volunteers and the public. They can recruit and support volunteer trappers, building TNR capacity. They can also save shelter resources, reducing intakes by focusing trapping efforts in neighborhoods where large numbers of surrendered kittens originate.

“I really felt like it had the possibility to make an enormous difference for not only the folks in our community but for the animals and our shelter.”

—Jeanine Cloyd, Humane Educational Society

For shelters that can’t dedicate a staff position to community cat work, Bays encourages them to make it a part-time position or part of an existing job. So many departments within a shelter are impacted by community cats, she says. “It’s really valuable to have that point person who can accurately explain the protocols and policies.”

At the Humane Educational Society in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Jeanine Cloyd became her organization’s first staffer to serve as a TNR point person in 2020, when the shelter moved into a new facility and “started getting serious” about community cats, she says.

Before then, the shelter’s TNR program consisted of one volunteer and a handful of sterilizations here and there. At the time, Cloyd had worked at the shelter for 13 years in a variety of education and volunteer management roles. She’d never trapped cats or fostered feral kittens, but she jumped at the chance to take charge of the program.

“I really felt like it had the possibility to make an enormous difference for not only the folks in our community but for the animals and our shelter,” she says. “So that instead of keeping like 250 kittens in foster care every month from May through November, we could use those resources for training, enrichment and all kinds of different things.”

Today, as education and community outreach manager, Cloyd oversees the shelter’s TNR program, barn cat adoption program, monthly vaccination clinics, off-site events and youth outreach programs. The bulk of her time is spent on TNR.

She works closely with Scratch Inc., a local TNR group whose six volunteers helped teach her the ins and outs of trapping and working with caregivers. She, in turn, has enabled the group to tackle larger cases than they previously could handle. She turned an empty room next to her office into a holding space for cats before and after their surgeries and recruited shelter volunteers to care for the cats and perform data entry.

Every week, Cloyd coordinates two trapping ventures, resulting in about 80 TNR surgeries a month. To increase that number, she and her team recently completed a yearlong shelter mentorship with the HSUS focused on building their TNR program capacity. Cloyd is now working to enlist more volunteers—and hopes the shelter will soon have the resources to add another TNR-focused staff position.

“All shelters should be hiring someone for this job,” Cloyd says. “If we don’t go out in the community and hit [cat overpopulation] at the roots … we’re just a Band-Aid. We're just spinning our wheels.”

The path to ‘good, fulfilling work’

Some community cat coordinators focus on TNR programs, some oversee their shelter’s return-to-field program and some manage both. Just as their jobs vary, so do their backgrounds and experience.

Many start as volunteers, trapping cats in their neighborhoods with no expectation that it will lead to a career change. Others transition from jobs in animal services, community outreach or other shelter roles. Still others simply have a love for animals and a passion for making positive change in their communities.

No matter their background, community cat coordinators need to enjoy trapping cats and being out in the field. “It’s definitely a job for people who like things that are dynamic and can adapt to the situation,” says Bays.

Volunteer management skills are another big asset, says Cloyd, who created a private Facebook group for her TNR volunteers where she shares success stories and kudos. It helps build camaraderie and a sense of a shared mission among volunteers, she says, and enables her to “remind them that what they’re doing is really amazing.”

Planning, scheduling and communication skills are also key. Before she started trapping cats for HSSA, Fahey worked at a wildlife rehabilitation hospital where she helped troubleshoot complaints about urban wildlife and guide people to humane solutions. The experience has served her well in her TNR work. “Reducing conflict between people and cats is a big part of our job,” she says.

Patience is another good trait for a community cat coordinator, Fahey adds, particularly if your shelter’s TNR program is relatively new. Just as it takes time to catch those last few holdouts in a cat colony, it takes time to build a volunteer corps and the capacity to meet your community’s TNR needs.

Cody Czajkowski discovered the value of a long-range view after he moved to Perryville, Kentucky, in 2018 and purchased a fixer-upper that came with about 25 outdoor cats. Since he was new to the area, Czajkowski didn’t know about the local shelter or resources for community cats. He simply bought some traps and paid out of pocket for spay/neuter surgeries at private veterinary practices, working a series of odd jobs to cover the expenses.

“No offense to game designers, but I want a job where I’m actually doing something.”

—Cody Czajkowski, Danville-Boyle County Humane Society

After three years, he was going broke and beginning to feel burnout. That’s when Danville-Boyle County Humane Society offered him a part-time job as a cat trapper. Czajkowski had been trying to think of ways to raise money for the cats’ veterinary bills but “never would have dreamt” that he could get paid to trap cats, he says.

His first year with Danville-Boyle, Czajkowski used his own vehicle to transport cats to veterinary clinics. His home served as the holding space for cats before and after their surgeries, and his girlfriend helped care for the cats. “It wasn’t uncommon for us to have 10 to 20 cats in traps in our kitchen,” he says.

The second year, with guidance from the HSUS Shelter Mentorship program, the shelter purchased a van for cat transport, created a cat holding space within its facility, and recruited volunteers to help with feeding and cleaning, which freed up more of Czajkowski’s time for trapping. The third year, Czajkowski’s job was upgraded to a full-time position.

As the program has grown, so has its impact. Feline euthanasia numbers have plummeted, from about 500 or 600 cats a year before Czajkowski was hired to a handful of cats who are sick and beyond saving. Staff and volunteer morale has increased, and relationships with the five local veterinary clinics that provide spay/neuter surgeries for the shelter have improved.

When the shelter relied on caregivers and volunteers to trap cats, missed appointments were common, says Czajkowski. Now, he’s trapping full-time, often past midnight, to make sure they fill their reservations.

It’s not the career Czajkowski envisioned when he graduated from college with a degree in 3D animation and computer design. Still, “and no offense to game designers,” he says, “but I want a job where I’m actually doing something.”

Trapping cats, working with caregivers and resolving problem situations isn’t easy, but he enjoys helping people and seeing ear-tipped sterilized cats thriving in their outdoor homes. “It’s good, fulfilling work.”