Claw and order

VCA adds a nail in the coffin of elective declawing

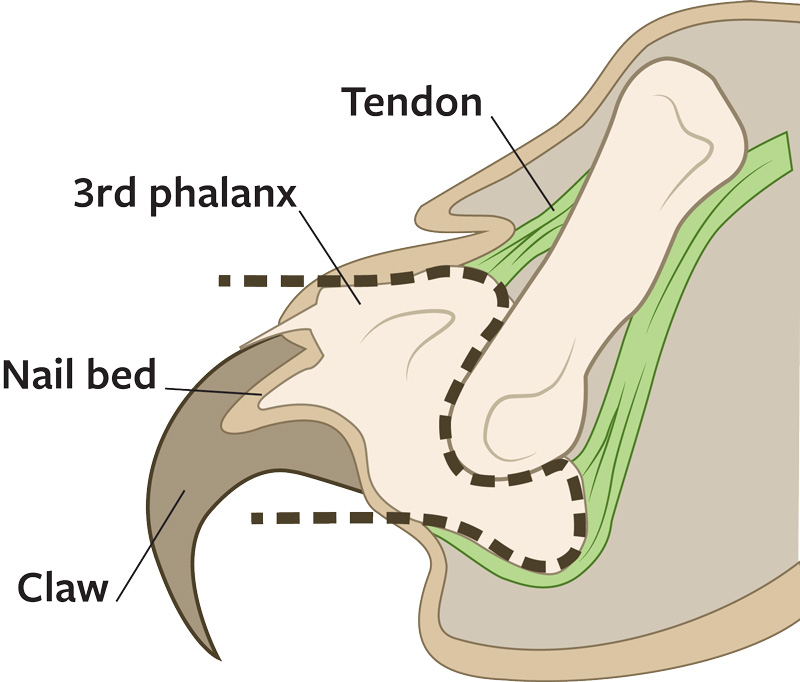

It was the worst cat declaw Beth Wellman had ever seen. A botched laser procedure had sliced through the first joints of each of Princess’s front toes and damaged the adjacent bones. She was walking on bare bone, says Wellman, director of the Humane Society of Midland County in Michigan, and the chronic pain had led her to lick all the fur off her paws.

The pain also caused Princess to become aggressive and stop using the litter box. Her owner then banished her from the house, leaving her outside to fend for herself. By the time she arrived at the shelter, Princess was miserable, emaciated and “untouchable,” says Wellman.

Princess is just one of six cats suffering from declaw surgeries gone awry who have come into the Midland shelter in recent years. But even when the surgery is performed correctly, cats can experience long-term emotional and physical problems.

For decades, animal advocates have lobbied to outlaw declaw surgeries—except for the rare cases when it’s medically necessary, such as the removal of nail bed tumors, says Dr. Barbara Hodges, director of advocacy and outreach at the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association. HSVMA has submitted legislative letters in support of declaw bans, testified at legislative hearings, lectured at veterinary schools, and worked to raise public awareness of cosmetic and convenience procedures—including declawing and tendonectomy of cats—that yield no medical benefit to the animals.

Declawing is already outlawed in dozens of countries and seven of the 10 Canadian provinces, and the U.S. is starting to catch up. Ten U.S. cities now prohibit the procedure, and in 2019, New York became the first state in the nation to ban elective declawing.

Another victory came in February of this year, when VCA United States animal hospitals, owned by Mars Veterinary Health, announced that it would discontinue elective declawing at all of its practices, a policy that had already been implemented by VCA Canada, Banfield clinics and BluePearl specialty veterinary hospitals, which are also owned by Mars.

“We do not support the elective declawing of any animal in our veterinary practices,” VCA said in a statement on its website. “... Feline scratching and nail sharpening are normal behaviors and the removal of nails has been shown to lead to chronic pain and, in some cases, to cause long-term behavioral issues.”

In the U.S. alone, about 2,000 Mars-owned veterinary clinics will no longer declaw cats for the convenience of the owners. Instead, veterinarians will educate owners about environmental changes to properly channel their cats’ need to scratch. VCA has created a section on its Woof University website to provide member veterinarians with training and alternatives to declawing.

Two thousand veterinary clinics in the U.S. will no longer provide elective declaw surgeries.

The policy change has been well-received by VCA personnel, especially because individual hospitals and regions were involved, says Dr. Jennifer Wesler, chief medical and quality officer for Mars Veterinary Health. “We are easily aligned on this. It’s not a business decision, it’s a better-world-for-pets decision.”

The new policy was welcome news to Dr. Jennifer Conrad, founder and director of the Paw Project in Santa Monica, California. Originally founded to repair the maimed paws of declawed lions, tigers and other victims of the exotic pet trade, the Paw Project quickly expanded its focus to end all declawing.

In 2016, Conrad was invited to speak at VCA’s regional directors’ meeting.

“[I was] given an hour to speak about why I wanted them to stop declawing,” says Conrad. “The Canadian director understood it … and took it back to VCA Canada. Sure enough, in 2018 VCA Canada stopped declawing across all their hospitals.” The good press and feedback from Canadian clients intrigued VCA U.S. and gave additional credence to the philosophy that it was the right thing to do.

To relieve the suffering of declawed cats, the Paw Project offers grants to help shelters cover the cost of surgical paw reconstruction, which normally runs from $1,200 to $2,500.

Princess was one of the beneficiaries of the grant program. Her paws were in such bad shape that multiple surgeries were required. The orange tabby then went to a foster home to recover and learn to trust humans again.

Free of pain, Princess’s sweet nature resurfaced, and she started using the litter box reliably. Finally, at 9 years old, she was adopted into a loving home.

Hearing Princess’s story and those of the five other cats that the Midland shelter has been able to help thanks to the grant program, Conrad was elated. “Isn’t that the greatest?” she says. “I went to vet school thinking I was going to do endangered species. But I also love [domestic] cats, and to be able to change the world for cats on a big scale is very gratifying.”