New resource aims to improve rabbit housing in shelters

The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ guidelines focus on an overlooked shelter population

While cats and dogs make up the majority of animals in most U.S. shelters, rabbits have become a common sight at many organizations. But few sheltering resources focus on this population. That’s starting to change.

In September, the Association of Shelter Veterinarians released the first document of its kind in North America: comprehensive, species-specific recommendations for rabbits housed in shelter settings.

Not all shelters have a rabbit-savvy staff member or volunteer, says Lindsay Hamrick, director of shelter outreach and engagement at Humane World for Animals. “As more and more organizations serve as safety nets for rabbits, these guidelines are key to helping shelters meet rabbits’ unique housing and care needs.”

The challenges of caring for rabbits in a shelter

The idea for the guidelines started a few years ago when a group of shelter medicine experts were discussing the lack of resources devoted to shelter rabbits. They dug into the research and identified the pervasive lack of species-appropriate housing as a top priority.

“Many shelters were built before rabbits were commonly admitted and consequently rabbits are often housed in cages designed for other species (and sometimes inadequate even for those),” the guidelines state.

Rabbits typically stay in shelters longer than cats and dogs, which makes it all the more important to provide them with housing that promotes their physical and mental health.

“We know from experience with cats and dogs that getting housing right in the shelter lays the foundation for so much more,” says Dr. Kate Hurley, director of the UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program and a co-author of the guidelines.

As a prey species, rabbits are highly attuned to their environment. They’re sensitive to stressors such as being placed near predator species and being exposed to loud noises. Compared to dogs and cats, rabbits haven’t been domesticated very long. They retain many of their wild instincts, making a shelter environment particularly stressful for them, says Hurley.

Due to these challenges, the guidelines recommend that organizations prioritize options where rabbits can live outside a shelter, such as through foster home and self-rehoming support programs. “I think there’s…a fundamental mismatch between what shelters can offer and what rabbits need. They’re just not meant to be housed in a multi-species setting with lots of coming and going,” says Hurley. “Shelters should be a way station for rabbits [who] have been taken from an at-risk or some kind of crisis situation.”

The importance of humane housing for rabbits

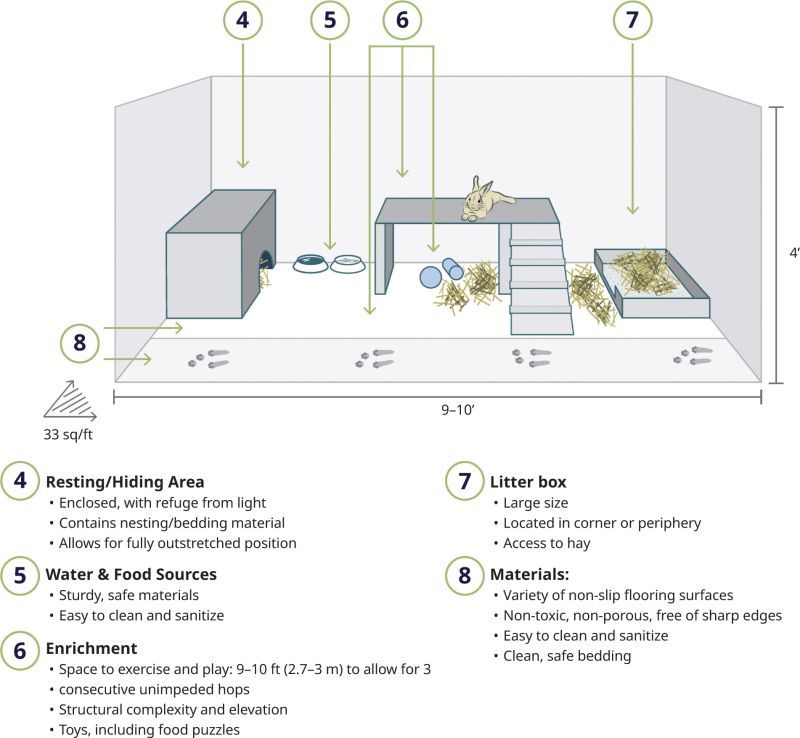

Even with alternatives in place, shelters may need to keep some rabbits inside their facilities. For these animals, the guidelines outline everything from lighting and cohousing to sanitation and infectious disease management.

Dr. Zarah Hedge, chief medical officer at San Diego Humane Society and a co-author of the guidelines, recognizes that the recommendations can seem overwhelming for under-resourced shelters. For example, the guidelines recommend cages that are large enough to allow rabbits to take three hops—substantially larger than the housing most shelters currently provide rabbits.

“The most important thing for shelters is to not think that they have to do everything at once, because certainly some of these are going to be longer term [goals],” says Hedge. “Maybe in the future if they build a new facility, [they can use] these guidelines to help guide how they’re going to build rabbit housing.”

Simply providing rabbits choices in how they engage with their environment can also go a long way, Hedge notes. A small study at a UK university found that giving rabbits enrichment items such as tunnels, balls and boxes almost halved their stress levels.

The ASV has already heard from shelters that are implementing changes based on the guidelines, Hurley says. “There’s a lot of excitement about having some clarity about what rabbits need and why they need it.”