Downloadable checklists: From crisis to care

Partnerships, planning and protocol are vital to emergency sheltering

How on Earth did Noah keep things straight with all of those animals jam-packed in the ark?

It’s a tale as old as time, but if your animal welfare organization ever responds to a natural disaster or large-scale cruelty situation, you might find yourself wondering about Noah’s intake procedure.

Whether you have 15 pregnant goats, 50 roosters and hens or 100 dogs and cats with varying medical conditions, good planning and proper procedures can keep you and your staff from pulling a month’s worth of all-nighters, forgetting which tabby is the biter or contracting a zoonotic disease. It’s important to create standard operating procedures ahead of time for crisis scenarios, but if the floods roll in or the dogs are seized, you’ll also need to be flexible and adapt those procedures to the specific situation.

The challenges of emergency sheltering can include finding a location that allows for electricity, water, communications and transportation; designing and constructing a space that considers capacity, care and disease control; coordinating with other animal welfare professionals, volunteers, veterinarians, government officials and law enforcement agencies; implementing intake and triage procedures for a large number of animals; gathering and training a transitional staff; carrying out daily operations from feeding to emotional and physical enrichment activities; reuniting animals with owners or rehoming those who have been displaced permanently; and closing up shop when the operation concludes.

It’s a tall order—but it’s not impossible. Whether your emergency shelter is a warehouse, a barn or an off-season fairground, at least it won’t be a giant boat.

Planning and preparation

In any emergency sheltering situation, it always helps to have existing protocols and checklists that you can easily adapt to your temporary shelter location, as well as a list of available resources that will support the number and types of animals you’re expecting, says Sára Varsa, senior director of the Humane World animal rescue team.

Reach out in advance to other shelters and rescues to see if they’d be willing to partner with you in a disaster scenario by sharing staff or resources or helping to house and place animals, says Kimberley Alboum, director of Humane World for Animals Emergency Placement Partners (EPP) program. Keep in mind that when you’re handling a large-scale seizure, working with nearby groups may be best, but in the case of a major natural disaster, nearby organizations may also be impacted—a good incentive to broaden your regional networking.

In general, be familiar with your community’s overall disaster plans. Your local office of emergency management (OEM) might have predefined roles or pre-allocated resources for shelters during a disaster, so ensure that your disaster plans are in line with the larger disaster plans for your area.

“Have a relationship with your OEM to make sure you know the full scope of what’s expected of you or what assistance they may have,” says Varsa.

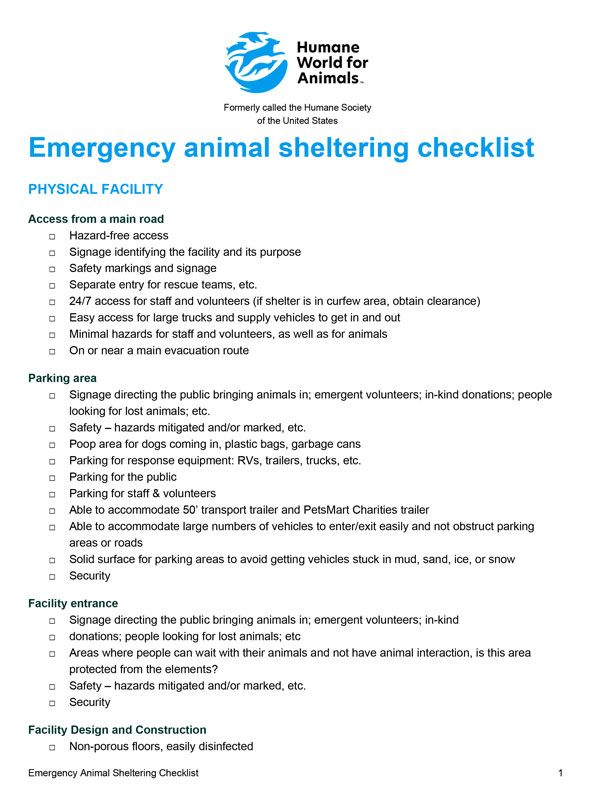

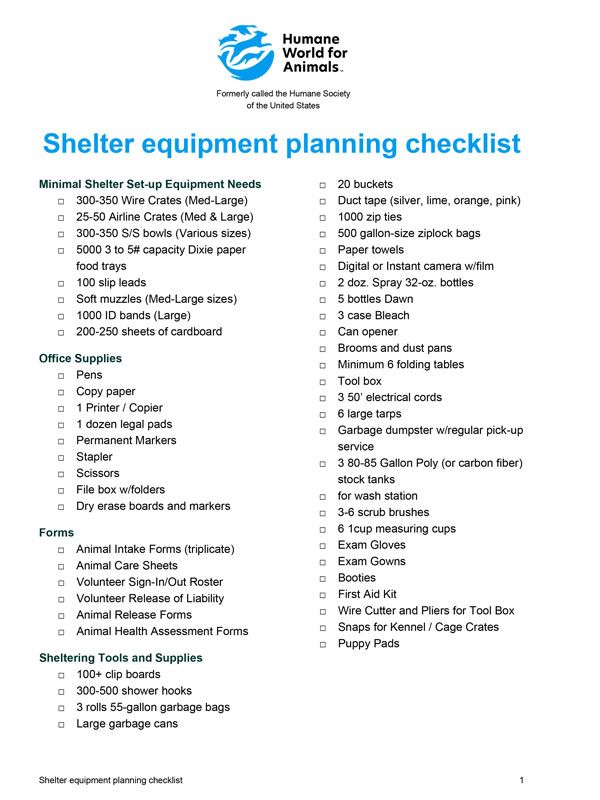

Varsa recommends using the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) incident command system to organize staff and volunteers and create job descriptions. Consider drafting daily operational flowcharts and schedules; liability waivers for volunteers; animal intake, release and health assessment forms; a checklist of emergency shelter supplies; and general protocols for intake, identification, cleaning, feeding, daily monitoring of animals and enrichment activities. If you’re dealing with a natural disaster, you’ll also need reunification processes for lost and found animals.

If you’re able to anticipate a major crisis—often possible with planned seizures—you can also reach out to national animal welfare organizations, says Alboum. They may be able to provide grants, disaster response teams and consultants—the ASPCA might call upon its response partners, for example, while Humane World for Animals might use its EPPs.

You can also beef up your shelter and rescue networking and foster goodwill by applying to become a response partner or an EPP yourself, after which you may be called upon to help other organizations during a disaster (which, in turn, may help you during your own disaster).

During a Humane World-led puppy mill rescue of almost 300 dogs in Fayetteville, Ark., in March 2016, the Humane Society of Saline County (HSSC), an EPP 200 miles away, was able to provide two buildings for use as temporary shelters, moving its own animals into other buildings and surgery areas, says director Ann Sanders. Post-sheltering, Humane World for Animals and EPPs transported dogs to other facilities, while HSSC housed and placed the remaining 60-plus animals, including mothers and puppies.

“The logistics associated with one of these cases are mind-blowing,” says Alboum, so the support of partner organizations is critical.

Although some animal cruelty cases require caution and confidentiality, you can discreetly enlist the help of trusted local and state disaster response committees, animal and agricultural teams, veterinary schools, the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association and foundations like PetSmart Charities. Ask local veterinary clinics if they’d be willing to take any animals in critical condition. If potable water is difficult to come by, consider asking the local office of emergency management, the community fire department, a utility company or even retail stores to bring in water or donate pallets of bottled water.

“Maintain good relationships with the people and businesses in the community,” says Varsa. “Your success is in the foundation of your partnerships.”

Location and leasing

If you’re unable to house displaced animals through a shelter collaboration or a boarding facility, reach out to local law enforcement or a commercial real estate agent to identify a building suitable for use as an emergency shelter.

In the event of a man-made disaster, your law enforcement point of contact can help to identify trusted community members and discreetly disclose details to building owners, but in general, disclose details on an as-needed basis to avoid compromising the case.

“Make sure you’re taking all the steps to maintain confidentiality without being misleading about your intent for the building,” says Varsa. “You will have animals in the building; you will be bringing in dogs and cats.”

During a tornado, hurricane or other natural disaster, your emergency facility will likely provide shelter for owned pets and strays, so choose a building that’s easily accessible to the public. With potentially scarce resources, pet owners in crisis and an influx of volunteer responders, supply runs will be a necessity, so your shelter should be close to airports, grocery stores and pet supply stores.

When you’re preparing a temporary shelter for a cruelty or neglect seizure, choose a building that’s the opposite: not readily accessible. You don’t want nosy neighbors snapping photos or friends and family of the case’s perpetrators attempting to reclaim animals or confronting staffers.

In all cases, consider how long you’ll need to use the location and evaluate road access, parking, plumbing, HVAC systems, electricity, cost, size and internet access. Does the location have sealed concrete floors and a nice high ceiling that won’t retain smells? Is it fully enclosed? How about its proximity to residential areas? Even the most animal-loving of neighbors likely won’t appreciate a concert of dog barks and rooster crows in the wee hours of the morning, so check to ensure you’re in compliance with local zoning ordinances.

Consider commercial business districts and industrial spaces—anything from an old machine shop to an old airport bay can serve as your shelter. Some building owners might be leery of housing a large number of animals, but reassure them that your intent is to leave the building better than when you found it, says Varsa, who obtains reference letters from previous building owners she’s worked with and ensures the premises are ready for new tenants when the rescue operation ends.

If you’ve signed a lease agreement and obtained a certificate of insurance, the local fire department can walk through your shelter, ensure it’s up to code and help you create an evacuation plan in the event of (another) emergency.

Capability, not capacity

It’s critical to think about your capability to care for the animals, not simply the space capacity of your emergency shelter, to ensure effective disease control and the mental health of the animals. Cats need 2 feet of space between their resting spot, food and water and litter box, for example, and dogs need space to exercise. Plus, it’s important that your shelter has space to accommodate unexpected additions.

“You have to be able to make reasonable and sound decisions based on what you’re presented with,” says Varsa. In the case of one puppy mill seizure, Varsa’s team had prepared for 100 animals—only to discover close to 300 once they were on site. At that point, she says, your team might be using space intended for animals experiencing anxiety or scrambling to build additional enclosures.

You don’t need to be an architect to design an emergency shelter—a pencil sketch on paper will do. Just be sure to consider the layout and spacing of cages for disease control, ease of cleaning and flow of staffers; space for offices, storage and expansion; exercise pens; maternity areas; veterinary treatment areas; species- and illness-specific isolation areas; quiet areas for animals who are visibly distressed; spaces for responders to eat, take breaks and use the bathroom; and a loading dock.

“During a natural disaster, we’re going to set up our shelter so that owned and vaccinated animals go here, owned animals without vaccine history can go here. I’m going to put animals that are brought in from the field here, by species,” says Varsa. “So you’re creating spaces for all your scenarios. And in that sense, you’re trying to quarantine the population from each other.”

You’ll also want to consider extraneous circumstances. You don’t want to “enrich” your animal environments in ways you didn’t intend—i.e., you’ll need to separate predator from prey and intact males from in-heat females. Kennel or fencing panels are incredibly useful for defining separate areas, and you can even tape cardboard boxes between cages to serve as visual and physical barriers.

A former Humane World shelter contractor also created the “pod system,” now used throughout the animal rescue and response community, in which emergency shelters are separated into pods of roughly 25 animals, each with its own dedicated equipment, staffers, exercise pens and signage.

“It helps with cross-contamination, disease control. Emotional health and well-being of the animals is another benefit, because they have dedicated caretakers,” says Varsa. “With consistent care, our volunteers can note changes in behavior and appearance, because they serve as ‘house moms and dads.’ They can look in and say, ‘C301 ate breakfast yesterday, and now C301 is not eating breakfast.’”

Shelter staffing

When choosing people to staff your emergency shelter, “you’re looking for somebody who’s committed and can follow directions,” says Varsa. “Everything else can be worked out. You just have to have an appreciation for the incident command system (ICS) and follow directions.”

Refer to your pre-planned ICS and assign leaders to each role. Depending on your operation and staffing capacity, consider appointing an incident commander, public information officer, safety officer, operations chief, daily care manager, veterinary manager, field manager, transport manager and intake manager. A designated animal behavior lead can oversee the staff and volunteers performing daily care and enrichment. Leaders should receive and read general protocol binders, and you should build daily command briefings into your emergency shelter operations. Look to your own staff, consultants, partner organizations, the local community, temp agencies or personnel resource agencies for your staffers and volunteers.

Veterinarians with certificates in shelter medicine or veterinary forensics are ideal veterinary managers, but any trusted veterinarian can serve as your medical lead or act as a consultant after initial exams (veterinary technicians are often capable of handling day-to-day treatments). Most often, veterinarians must be licensed in your state (even then, there’s plenty of red tape to consider—enlist the help of your state veterinarian).

Ideally, your team leaders will be in it for the long haul, but during a disaster or a long-term operation, consider how you’ll manage shift changes and shared roles. Handle transitions by having leaders document their responsibilities and daily schedule, ongoing projects and notes specific to special-needs animals in a binder that they can easily share. Place a whiteboard outside each pod, where staffers can note animal behavior or health concerns (think appetite, stool, urine, vomiting, sneezing or runny eyes) and associated IDs. Cage cards should include details such as “eats plastic; no Kong toys.”

When it comes to daily care, such as feeding, cleaning and walking, assign a minimum of two people to each pod, says Varsa, or roughly one person to every 10 animals in your shelter. Post simplified protocol and daily care schedules in each pod, such as a basic daily care flowchart (safety check, feeding, daily observation forms, etc.). Volunteers are often temporary, so it’s important to provide each newbie with a job description and have them shadow a more experienced person. Consider a quick briefing, providing the how and why of general protocol and a who’s who of staffers.

People responding in advance to large-scale cruelty cases or other major seizures are typically asked to not travel in attire that identifies them as part of an animal group, “so that they’re not drawing attention to themselves,” Varsa explains, and “we have covers for some of our logoed vehicles. For booking hotels, we just tell them that we’re there for a training exercise, and that tends to not be a problem. Normally the media will grab ahold of the case right after it happens, and then you walk into the hotel and people are like, ‘You’re our heroes!’”

Even beyond the obvious—from crates to pet food to disinfectant—emergency sheltering is all about supplies and resources. See examples of emergency sheltering checklists below.

Intake and illness

Enlist your most caring and compassionate staffers and volunteers for animal intake during a natural disaster—working with upset, stressed-out owners handing over their beloved pets, if only temporarily, is emotionally demanding work.

During any disaster, your intake and admissions team should include a data entry staffer handling forms and vaccination records, assigning ID numbers and documenting the animal’s ID, name, gender, breed, color, owner name, address, emergency contact and cage location, as applicable (for tracking software, try Chameleon, PetPoint or just Excel). For owned pets, you might have two chocolate Labs or three Maine coons, so document specifics like one white paw or a crooked tail.

A photographer should also take a photo of each animal with his owner, if applicable, plus a photo of the animal alone with a whiteboard detailing the date, ID, location and owner’s name. Have a veterinarian check for contagious illnesses, take blood samples, administer deworming medication and give vaccinations, if necessary, and a handler at the ready to attach ID bands, write cage cards and transport animals to their pods as soon as intake is complete.

If you’re dealing with a cruelty case, your veterinarian may have already performed an abbreviated field exam during the seizure, documenting the animal’s body condition score and any visible injuries, and the animal may already have been assigned an ID number (the next day, the vet should perform a more comprehensive intake exam). Animals might also have already received vaccinations on site, depending on state regulations and the situation, says Varsa.

Each species will have its own vaccination considerations, and most states require vaccinations to move animals across state lines.

In an emergency shelter, “you plan that you’re going to get some stuff,” says Varsa. “Kennel cough may move through the population, regardless of your precautions. So you’re watching closely for those symptoms and medicating for that as soon as you see it and ensuring there’s appropriate housing to isolate those animals when it occurs.

“You’re basically going in thinking, ‘This is a little vector of disease, and how are we going to manage it?’ So you work the problem backward. I’m going to double glove; I’m going to gown; I’m going to monitor all urinary and fecal matter.”

Handling protocols can also minimize the risk of cross-contamination. “We tend to want to immediately handle rescues as our own. We want to take the little puppy out of the enclosure and wipe it all off and snuggle it. This will come in time,” Varsa says.

“The best thing to do is ensure that they’re safe, they have a schedule and that they know what to expect of you. We’re not just thinking about it from the perspective of disease, we’re thinking about it as, ‘How can we create the most stable animal that can go and have a future with a family?’”

Curiously, being a disaster survivor can sometimes secure a pet’s future with a family, generating a boom in adopter interest and increasing adoptions overall.

Publicity means placement

Curiously, being a disaster survivor can sometimes secure a pet’s future with a family, generating a boom in adopter interest and increasing adoptions overall. Over in Saline County, word of the 300-dog puppy mill rescue spread. “It was all over the news,” says Sanders. “Whenever people see something in the news like that, they want to adopt.”

Families called, emailed, Facebook messaged and drove in from Texas, Tennessee and New York trying to get their hands on one of HSSC’s puppy mill rescues. One would-be adopter attempted a $600 bribe; another woke up at 4 a.m. to drive from out of state to the HSSC adoption event. On the day of the event, “We had at least half of the population of the town in our parking lot. The highway was lined both directions, coming and going,” says Sanders.

Every available puppy mill rescue was adopted, totaling 55 dogs, plus 13 of HSSC’s regular shelter dog population. One of the 13, adopted by a father-daughter duo, had arrived at HSSC a few days prior with a large hot spot on his back and had subsequently been shaved by a vet. “This poor dog … he would have taken forever to get adopted,” she says. “[The adoptions were] 100 percent the publicity. ... I’m thrilled to death.”

Documents