Detecting pain in cats

With tools and training, pet parents and shelter workers can ensure that cats don’t suffer in silence

Cats have many ways to say, “Feed me.” Race you to the kitchen. Rattle the bedroom door at 4 a.m. Sit by the empty food bowl and stare at you with eyes of doom. There’s no missing these messages.

What do cats say when they’re ailing? More often than not, not much.

One day, you suddenly notice that your cat seems thinner, is leaving food in the bowl, and is holed up in a closet most of the day. A vet visit reveals that your cat is ill and may have been in pain for some time.

How could you not notice? It’s not you. Cats are simply masters at hiding signs of infirmity. They’ve been known to suffer grievous injuries and illnesses without a sound.

This instinctive behavior is directly related to cats’ millennia-old role as a predator. In the wild, a predator who exhibits any kind of weakness is apt to “become somebody else’s lunch,” says Dr. Robin Downing, owner of a veterinary clinic and the Downing Center for Animal Pain Management in Windsor, Colorado.

Some indications of illness, such as limping, seizures or explosive diarrhea, are obvious. Signs of chronic pain caused by “hidden” ailments such as arthritis or cancer, however, can take time to reveal themselves. They often consist of small changes in everyday behavior that may not register with their human caretakers immediately.

Even veterinarians can have trouble detecting pain in cats.

Even veterinarians can have trouble detecting pain in cats. Anxious at being in the unfamiliar environment of the clinic, cats may refuse to come out of the carrier or try to hide or escape, making it hard to evaluate their gait, or they may not react to what should be a pain-inducing palpation.

“How are we going to have a clue that something might be amiss?” asks Downing. “We’re forced to think about changes in behavior.”

For that, Downing relies heavily on her clients’ observations. Reporting that a cat doesn’t jump on the sofa anymore, a sign that pain may be inhibiting mobility, is good information, but Downing wants more. She asks her clients to observe their cats’ eating, drinking, grooming and resting behavior; temperament; and social interactions, all of which contain valuable clues about a patient’s physical comfort.

Keeping a journal and taking photos and videos of your cat’s activity (or lack of activity) at various times of the day can provide valuable information for your veterinarian. "Your cat communicates their comfort or discomfort through body language," says Tabitha Kucera, a veterinary technician specialist in behavior and owner of Chirrups and Chatter. "Every cat exam should include videos of cats walking, playing and eating.“

Downing directs clients to a couple of online tools, such as the cat mobility checklist by pet health care company Zoetis. The simple illustrations contrast the movements of a healthy cat with those of a painful one so that their caretakers can better spot signs of osteoarthritis pain.

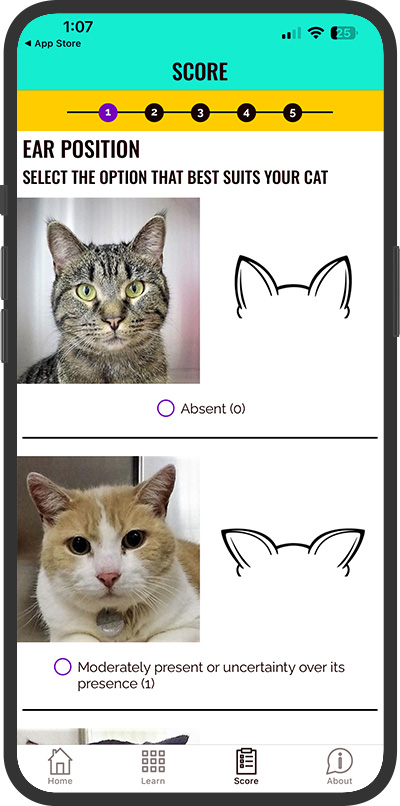

Downing also strongly recommends the Feline Grimace Scale, an online tool and mobile app developed by the faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Montreal by filming and studying patients of the university’s veterinary teaching hospital.

Looking solely at feline facial expressions, the scale evaluates and scores five characteristics: ear position, orbital tightening, muzzle tension, whiskers position and head position. After practicing with an online training manual, users compare their own cats’ expressions to photos in the Feline Grimace Scale app to ascertain their pets’ pain level.

“It’s easy to learn, easy to see. I think it’s amazing,” says Downing. “You pull it up on your phone, compare it to your own cat’s videos. It’s a great way for a layperson to learn.”

Identifying pain in shelter cats

In training sessions for animal shelter staff, Kucera uses the grimace scale and other tools not just to unravel behavior issues but to educate caretakers on signs of pain and how pain, not personality, may be affecting a cat’s attitude.

“Learning body language is essential,” she says.

So is teamwork. Kennel staff are on the front lines, so to speak, interacting with the cats on a daily basis, while the veterinary team may only see them occasionally. To properly diagnose and relieve a cat’s pain, “communication between veterinarian and … staff is huge,” says Kucera. As part of her trainings, she teaches shelter staff how to convey accurate, concise information to the veterinary team.

Kucera first became interested in feline pain and behavior while working in general veterinary practice. She noticed the challenges caregivers faced in recognizing pain and understanding cat behavior, as well as the lack of resources to support them. This often led to cats not receiving veterinary care until severe symptoms appeared. The experience motivated her to earn several behavior certifications with the goal of equipping caregivers and animal professionals with the tools and knowledge to identify pain in cats.

When training shelter staff to recognize and understand body language, including pain signals, Kucera encourages them to describe behaviors rather than use labels like grumpy, mean or spiteful. “Labels fail to explain behavior or its cause,” she says. “And they can’t be tested.” Once a label is attached to a cat, caretakers may attribute unwanted behavior to innate temperament rather than consider physical or environmental issues.

Labeling behaviors can be particularly problematic in a shelter setting since staff may not know how a cat previously behaved in a home. Fear and anxiety from being in an unfamiliar environment can cause some cats to display signs of depression such as hiding or refusing to eat, while others may appear aggressive, hissing and swatting when approached. If a cat is showing changes in behavior or signs of stress and fear, it’s important to assess environmental stressors and consider underlying medical issues, including pain, that may be contributing to or causing the behavior.

In her workshops, Kucera teaches scoring systems for fear, anxiety and pain, using photos and videos to highlight overlooked behaviors. With training, caregivers learn that signs of feline pain aren't so subtle after all. “Once they see it, they can’t unsee it,” she says.