Crisis of veterinary care

How can nonprofits survive the veterinary workforce shortage?

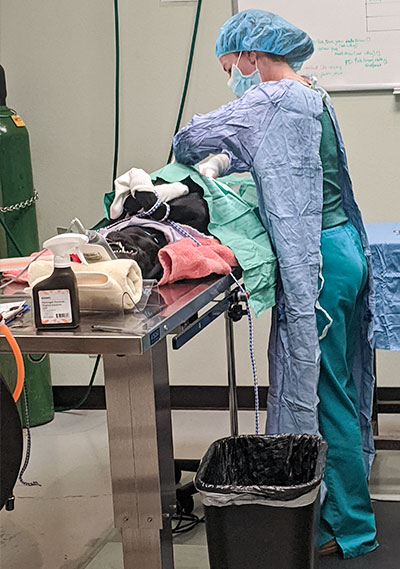

It started with a cat rescuer, a veterinarian and a commitment to help community cats in Bend, Oregon. With help from about 10 other volunteers, the Bend Spay & Neuter Project launched in 2004. Surgeries were performed on weekends in the rescuer’s garage.

By 2021, when it celebrated its 50,000th surgery and was operating as a program of the Humane Society of Central Oregon, the clinic had its own building with two surgery suites, seven paid staff members and a cadre of longtime volunteers. The only nonprofit clinic in a three-county area, it offered low-cost spay/neuter surgeries, wellness clinics and a pet food bank.

“It was such a labor of love from the time it opened,” says Megan Gram, who started volunteering at the clinic in 2008 and served as its executive director from 2012 to 2017. She recalls the long nights she, her boyfriend and other volunteers spent renovating the clinic interior, painting walls, installing floors and widening doorways. She also remembers the clients who drove from as far as three hours away to get veterinary care.

“It became very important to people who couldn’t afford a regular vet,” Gram says. “A lot of our clients ended up being volunteers. If they couldn’t pay for it, they’d volunteer.”

Then in April of last year, the clinic’s veterinarian received a job offer she couldn’t turn down. Dr. Crystal Bloodworth, lead veterinarian at the humane society, tried not to panic. She went through all the usual steps to recruit a new clinic veterinarian and reached out to her vet contacts. But as the months ticked by, only three people expressed interest in the position. Before they even got to the stage of discussing salaries, all three candidates accepted other jobs.

By late summer, the clinic went from operating four days a week to one, with Bloodworth taking time from her shelter duties to perform spay/neuter surgeries for the public. “We tried to hobble along in that capacity,” she says, but there were shelter animals who also needed surgeries and other medical treatments, and the shelter itself was understaffed. In early September, the humane society made the difficult decision to temporarily close the clinic, anticipating it would take two to three months to hire a new veterinary team.

In early September, the humane society made the difficult decision to temporarily close the clinic, anticipating it would take two to three months to hire a new veterinary team.

That was seven months ago. The clinic’s veterinary assistants and support staff have moved on to other jobs. Kitten season is approaching, and Bloodworth and her shelter staff dread the impact of the clinic’s closure on their intakes.

“The clinic is fully stocked and set up to do so much for our community,” Bloodworth says. “We’re grasping for people to come and work in this capacity.”

But the odds aren’t in their favor. According to data from the American Veterinary Medical Association, in 2021 there were more than 18 openings for every veterinarian seeking a job and nearly six for every veterinary technician or assistant.

It’s one symptom of a veterinary workforce shortage that is affecting clinics across the country and which, according to a study by Banfield Pet Hospital, could leave 75 million pets without access to vet care by 2030.

As the shortage intensifies, animal welfare leaders around the country are asking the same question: What do we do when they aren’t enough veterinarians to go around?

How did we get here?

Aimee St. Arnaud, founder of the Open Door Veterinary Collective, has spent most her animal welfare career helping to establish nonprofit clinics around the U.S. She saw the early warning signs of the vet shortage nearly 10 years ago, when shelters and spay/neuter clinics found it increasingly difficult to hire and retain veterinary staff.

“Nonprofits tend to be the canary in the coalmine,” St. Arnaud says. “Because they often can’t compete with corporate practices in terms of benefits and compensation, they tend to be the first impacted.”

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic hit, forcing many clinics to close temporarily, scramble for supplies and navigate the challenges of curbside service, the system was already strained. But the veterinary shortage isn’t a pandemic problem but largely a numbers problem that has been years in the making, says Mark Cushing, founder and CEO of the Animal Policy Group.

With baby boomer veterinarians retiring and an estimated 4,400 job openings for vets each year, vet schools aren’t graduating enough students to fill them and meet the needs of a growing human—and pet—population.

“From 1978 to 2014, a 36-year period, we opened one new vet school in the U.S.,” Cushing says. “We have 185 medical schools in the U.S. and only 33 vet schools, so it shouldn’t surprise anyone that we’re in this position.”

Small clinics like Bend’s are perhaps in the most precarious position: one resignation letter away from shutting down. But even large corporate practices are struggling to meet their communities’ needs.

The situation may grow worse. A Mars Veterinary Health study published earlier this year estimates the country will be short 15,000 veterinarians by 2030. And that doesn’t account for the number of vets who may leave the profession due to the stress of being chronically understaffed, Cushing says.

Small clinics like Bend’s are perhaps in the most precarious position: one resignation letter away from shutting down. But even large corporate practices are struggling to meet their communities’ needs.

“It’s hitting everywhere,” says St. Arnaud. “We’re seeing emergency clinics that aren’t accepting patients; they’re sending people two hours away. We’re seeing spay/neuter clinics that are cutting community cat surgeries …. We’re seeing universities that are shutting down their public programs completely. There’s a shelter in Texas that can’t fix pets before adoption because they’ve been looking for a vet for over two years so they’re having to give out vouchers. We worked so hard to spay/neuter before adoption; now we’re going backward.”

Desperately seeking …

In recent years, the animal welfare field has made remarkable progress in reducing homeless pet numbers and expanding access to care for owned pets. But most of the strategies that got us here—from high-volume spay/neuter clinics and trap-neuter-return projects to pre-adoption spay/neuter and community outreach programs—depend on the participation of skilled veterinary professionals.

With so much at stake, the search for solutions to the vet shortage has taken on a new level of urgency.

“To enhance, or even maintain, access to veterinary services in the U.S. … will require bold and immediate actions,” writes Dr. James Lloyd in the Mars study, whose recommendations include expanded educational capacity for both veterinarians and technicians, along with efforts to attract more people to the field through an “intentional, progressive emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Advocates from within and outside the vet industry are also pushing for new policies and regulations, such as modifying practice laws to allow veterinary professionals licensed in one state to work throughout the U.S. Other proposals involve changes in veterinary education, including the addition of mid-level professionals akin to nurse practitioners in human health care, and modifying curriculums so that vet students gain more hands-on experience (and are more practice-ready when they graduate).

Fortunately, when it comes to producing more vets, we’re headed in the right direction. During the past two years, three new vet schools opened, and Lincoln Memorial University in Tennessee announced plans to double its vet school enrollment.

This bodes well for the future, says Pam Runquist, executive director for veterinary outreach with the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association, but it will take years before today’s vet students become tomorrow’s job-seeking veterinarians with the experience to oversee a shelter’s medical program or perform high-quality seven-minute spay surgeries. Changes to laws, regulations and vet school curriculums will likewise take time.

Confronted with the needs of the here and now, animal welfare leaders took part in a panel discussion hosted last year by The Association for Animal Welfare Advancement on the topic of recruiting and retaining vet staff.

It will take years before today’s vet students become tomorrow’s job-seeking veterinarians with the experience to oversee a shelter’s medical program or perform high-quality seven-minute spay surgeries.

“We can’t even get people to answer our job ads,” said the director of a Washington shelter. Others had more encouraging news and advice to share. “We recently hired three new vets,” reported the CEO of a large New York shelter, “though we had two vets turn us down.”

The tips ran the gamut—from increasing salaries to implementing vet student internships to focusing on employee well-being. Several attendees reported that vets are attracted by the prospect of less client contact compared to private practice. Others said that structured training and mentorship programs are key.

In essence, to hire and retain vets in today’s competitive market, nonprofits need to take a holistic look at what they expect of vets and what they offer in return, says St. Arnaud, who co-chaired the discussion. And to do that, they need to understand the realities of the profession.

Put your best offer forward

Even in the best of times, veterinary medicine is a “challenging, emotionally draining world with life-or-death decisions and long physical hours on your feet,” St. Arnaud says. Injuries are common. Clients may yell at you. Burnout is high, and suicide rates are more than double those of the general population. On top of this, the average vet school graduate carries $183,000 in student loan debt and is at an age when many people want to buy homes or start families.

So salaries are important, along with health care, retirement plans and other elements of financial stability. But better pay alone won’t guarantee job satisfaction. In a 2020 AVMA survey, nearly 40% of veterinarians said they were considering leaving the profession, citing the lack of work-life balance as a primary factor.

“It’s been out of balance for so long,” particularly in the mission-driven nonprofit sector, says Dr. Sadina Scott, owner of the Family Pet Hospital of Shawnee. “It’s really important to structure the clinic so the team has work-life balance. Ultimately, they’ll be more productive and have [fewer] mental health issues.”

St. Arnaud agrees. The two clinics she co-owns recently reduced their hours, closing an hour earlier on weekdays and no longer operating on Saturdays. “It was hard to do,” she admits. “You have to weigh the needs of your clients and the needs of your staff, but if you don’t have staff, you’re not going to be able to help anyone.”

To protect staff from compassion fatigue and burnout, her clinics recently recruited licensed social workers as volunteers. Along with offering emotional support for staff, they help alleviate their workload by providing grief counseling for clients and guiding them through financial options for covering their pets’ vet care.

It’s all part of creating a positive workplace culture where staff feel valued and respected, says Dr. Kate Gray of the Humane Society of Utah. “We try to do things for our staff outside of work, treat them like human beings. People get sick; it’s OK to be sick. And we make sure they’re recognized … on a regular basis, and not just a pizza party.”

As more clinics make employee well-being a priority, St. Arnaud believes the vet shortage will have a lasting effect on how veterinary medicine is practiced. “We can’t just continue to try to force a model that is no longer working,” she says. “We need to think about it for the people who are taking care of the animals.”

That doesn’t mean change will be easy, adds Runquist. Higher wages, better benefits, reasonable workloads—these are big challenges for nonprofits that are struggling to meet their communities’ needs while keeping their services affordable.

Still, the animal welfare field has a long history of tackling seemingly insurmountable challenges, and many organizations are already finding innovative ways to cope with the vet workforce crisis. Some are turning to new tools, such as telehealth and smartphone apps, to maximize the capacity of the vet staff they have without adding hours to their workdays. Or they’re scrutinizing their clinic operations and discovering that small tweaks can add up to significant savings in money or time. Others, if they’re fortunate enough to have certified veterinary technicians, are restructuring workloads to take better advantage of their skills.

“We can’t just continue to try to force a model that is no longer working. We need to think about it for the people who are taking care of the animals.”

—Aimee St. Arnaud, Open Door Veterinary Collective

In an era when vets and techs are increasingly hard to find, “we need to think outside the box in a targeted, sustainable way,” Bloodworth says.

Which is what Gram did last spring after the shelter where she serves as executive director, Saving Grace Pet Adoption Center in Roseburg, Oregon, lost its vet. “We were all panicking,” she says, but she eventually learned of a veterinarian trained in high-volume spay/neuter, mother to a young child, who wanted to work part-time.

Gram reached out and said, “We want to hire you. What will it take?”

It took a flexible schedule, a dental and health care plan, and a salary that was more than the budget allowed for. Gram went to her board and said, “I need to be able to pay this person this amount of money.” She clinched the deal.

Three and a half hours northeast of Roseburg, the Bend spay/neuter clinic remains closed. But with help from a grant, Bloodworth and her team plan to launch a mobile spay/neuter clinic this fall.

It won’t be the same as having a brick-and-mortar clinic open four days a week, which everyone in the community knew about as the place to go, and they’ll need to start slow, holding events on days when they’re able to recruit volunteer vets, reschedule their shelter vets or hire vets available on a per diem basis. But without monthly rent and utility bills, the mobile model will make less frequent clinics a cost-effective solution and help meet the need in their community.

“We’re trying to stay positive about our mission and where we headed,” Bloodworth says. “As discouraging as it is, you always have periods where you don’t do as well as you hoped. Those of us who remain in this profession in the years of the ‘Great Resignation,’ we’re in it to win it.”