Face value

Applying facial recognition technology to lost pets

Browse any neighborhood forum, and you’ll find owners’ panicked tales of pets who have gone missing.

For those lost animals who eventually wind up in a shelter or rescue, only about 37% of dogs and 5% of cats will ever make it back home, according to 2018 data from Shelter Animals Count.

“I’d say the lost-and-found system for pets is broken in this country, but that presupposes it was ever actually working,” says Susanne Kogut, president of the Petco Foundation.

While adoption rates have improved substantially in recent years, nationwide there’s been minimal improvement in return-to-owner statistics, she adds, and one reason is the lack of a central place for reporting lost or found pets.

“It’s very scattered,” Kogut says. “In San Antonio alone, we have like five or six lost-and-found pages. Some of them say they’ll respond in three days; well, that’s the end of the stray hold.”

In addition to regional lost-and-found sites, there’s Craigslist, Nextdoor, Front Porch and a plethora of neighborhood Facebook groups. And since there’s no guarantee the person who found or spotted a lost pet knows about any of these sites, owners still need to post flyers on bulletin boards and telephone poles, knock on doors and regularly visit local shelters. The search for a lost pet can become a full-time endeavor, and not everyone has the resources, know-how or emotional fortitude to cover all the bases.

Only 37% of dogs and 5% of cats who end up in a shelter or rescue are reunited with their owners.

To remove some of the complexity, in 2017 the Petco Foundation invested in Finding Rover, a mobile app and website that Kogut hopes will evolve into a nationwide “one-stop shop” for reporting lost and found pets.

The site was founded in 2013 by John Polimeno after he saw lost pet flyers on a Starbucks bulletin board and wondered if advances in human facial recognition technology could be applied to pets. The answer was yes, and Finding Rover has since partnered with more than 6,000 shelters and rescues to apply new technology to an old problem, says COO Mark Marrello.

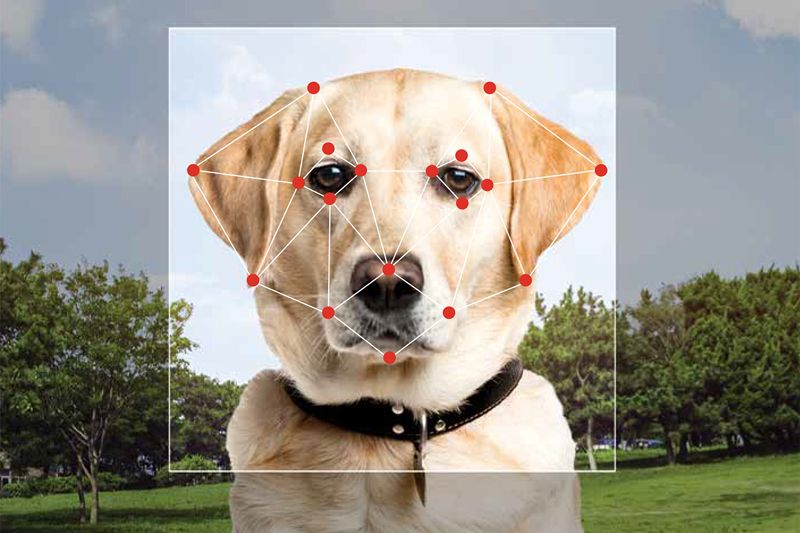

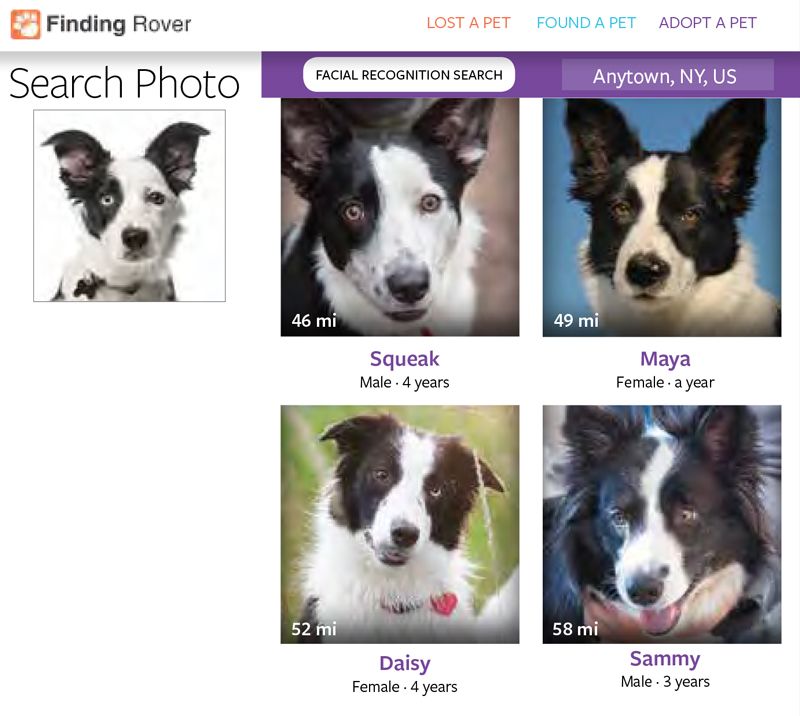

People who have lost or found a pet can immediately post a photo to Finding Rover via its mobile app or website. Using geographic filtering and an algorithm developed by researchers at the University of Utah to identify distinctive features on the animal’s face, the system returns a series of most likely matches. This saves people time scrolling through unrelated postings, and it avoids common miscommunications (e.g., the person who calls the shelter looking for a calico cat who has been labeled a tortoiseshell). As Mike Shumate, director of Pasco County Animal Services in Florida, puts it, if a dog or cat isn’t wearing a collar or doesn’t have a microchip, “he still has his face.”

The app can also help owners locate lost animals before they’re ever taken to a shelter, says Kogut. A neighbor spotting a lost animal “may not be able to catch that dog or cat, but if you can get close enough to get a photo and post it, it still enables that owner to go into that area and search there. It’s just simpler; all it takes is a photo and one place to post it.”

The process is also seamless on the shelter side, says Shumate, thanks to Finding Rover’s software that interfaces with commonly used shelter databases. After shelter staff upload photographs of animals to their databases, the photos automatically sync with Finding Rover’s database every hour.

In recent years, more than 19,000 pets have been reunited with their owners through Finding Rover.

In 2019, a year after Pasco County launched Finding Rover, its return-to-owner rate increased by 23%. Shumate doesn’t know how much of those gains can be attributed to the app, but points out that “you just can’t have enough tools for lost and found.”

In recent years, more than 19,000 pets have been reunited with their owners through Finding Rover. The system is free for shelters and rescues, as well as the 3,000 to 5,000 users who search the database on any given day. “We’re trying to make it the de facto lost-and-found search everywhere in the world,” Marrello says.

Kogut witnessed the promise of this technology two years ago when her co-worker’s dogs escaped from a backyard. She and her team immediately rallied to help, printing flyers, knocking on neighbors’ doors, posting on lost-and-found sites, and emailing the directors of area shelters. That night, Kogut uploaded photos of Ally and Elfie to Finding Rover, and within seconds their matches popped up.

“So I called [my co-worker] and said, ‘Stop crying. Here’s your dogs; this is where they are.’” When her co-worker went to the shelter in the morning, the woman at the front desk said that her dogs couldn’t be there since the facility didn’t take in strays. In fact, the shelter had recently taken in some strays to ease crowding at another shelter, and Ally and Elfie were among them. If her co-worker “hadn’t had those screen shots, they would have sent her away,” Kogut says. “She would have lost her dogs.”

As more shelters, rescues and the public use the system, Kogut believes Finding Rover will be a game-changer for lost and found pets and could save the sheltering field hundreds of millions of dollars by reducing unnecessary intakes and calls for animal control services.

“We love pet adoptions,” she says, “but there is nothing like watching a video of a lost pet reuniting with his owner.”