The light at the end of the rabbit hole

To survive the topsy-turvy world of animal rescue, you need a mission, a guide and a plan

On bad days, a friend of mine, who leads an all-volunteer rescue group, likens rescue work to falling down the rabbit hole. Just like the heroine of the Lewis Carroll classic Alice in Wonderland, she sees herself navigating a chaotic landscape with unexpected twists and turns, trying to make sense of people and situations that defy logic, and questioning whether she’s making any real progress.

Other rescue friends have their own favorite analogies: Running on a treadmill that they can’t get off, or getting sucked into a black hole.

If you’ve been in the field long enough, you can likely relate. Rescue work is emotional and often unpredictable. The foster kittens test positive for ringworm, the adopter is moving and can’t find housing that will accept her dog, the hoarding case explodes, the landowner wants the community cats removed by this weekend, volunteers are up in arms over a recent board decision, no one remembered to file for an extension for the group’s tax return.

It’s easy to become overextended and feel out of control, trapped in an alternate reality while your non-rescue friends lead “normal lives.”

But while rescue work will always have some element of unpredictability, there are time-tested strategies for giving structure and direction to your group’s efforts—ones that can help minimize chaos and burnout.

Here’s another popular analogy: Animal welfare is a lifesaving business. And just like any business, your rescue needs clarity, thoughtful planning and a firm grip on reality to ensure it succeeds and survives for the long haul.

Finding your purpose

“I know who I WAS when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

—Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

In the rescue world, a common path to self-destruction is known as “mission creep.”

This happens when you gradually broaden your original objectives and find yourself taking on more than you and your group can reasonably handle.

Rescue organizations often start with a “passion to tackle everything before building capacity,” says Sharon Harvey, president and CEO of the Cleveland Animal Protective League in Ohio. Before long, the spay/neuter program serving one county has morphed into a tri-state spay/ neuter, foster care, trap-neuter-return, community outreach, lobbying effort. And since there are still only so many hours in the day, people can start to sink under the weight of an unrealistic load.

Harvey cites the example of a rescue group that was “doing wonderful work” and filling a gap in animal services for families fleeing domestic violence in Northeast Ohio. “Unfortunately, they started to experience mission creep when they began to expand the definition of the types of families and animal situations they were trying to help with. They couldn’t keep up, and eventually they dissolved, which was a real shame. When they were very focused on what was already a big goal … they were making an impact that mattered. They simply tried to take on too much.”

Most rescue groups rely on volunteers, who often struggle to balance the demands of their volunteer roles with those of their paying jobs, personal and family obligations, and the mundane tasks of living. But even organizations with paid staff and multimillion-dollar budgets have limits. Determining your parameters and where to focus the bulk of your efforts can require a close examination of your community’s needs and existing services, as well as a lot of soul-searching and group discussions.

When counseling organizations that have taken on too much and are struggling to set priorities, Tom Tholen, senior vice president of marketing and development at The Association for Animal Welfare Advancement, starts with a fundamental question: Why does your organization exist?

This isn’t just a question for new organizations; many established rescue groups struggle to articulate a clear identity. Helping animals is a given. But who decides what form that help will take and which programs will be top priorities? Lack of clarity on these points can lead to mission creep and the burnout that comes from working beyond your capacity.

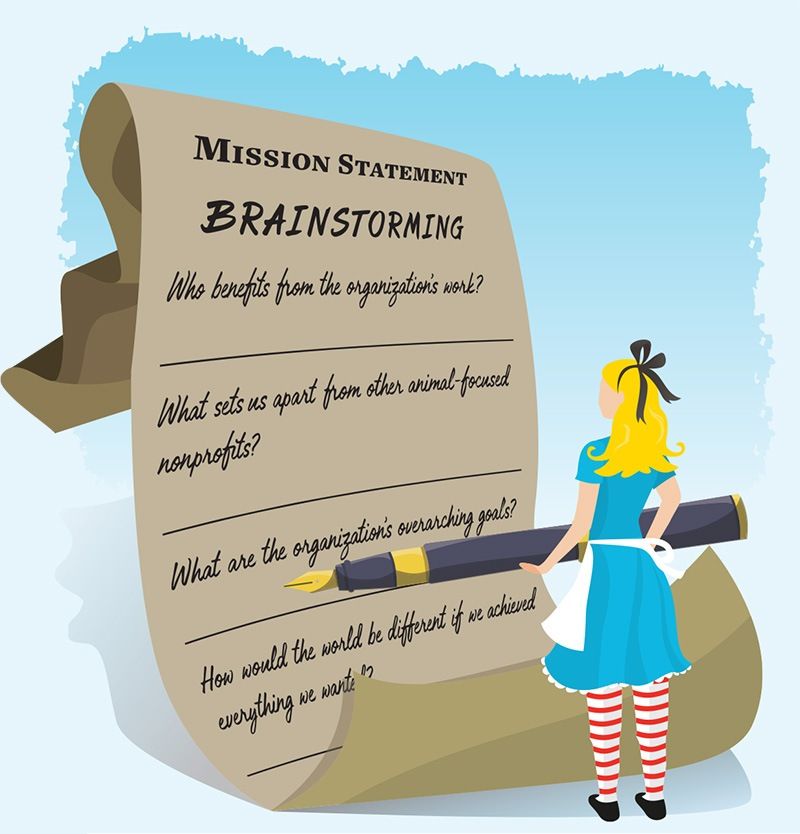

At meetings with a group’s stakeholders, Tholen hands out index cards and asks people to write down the words and phrases they believe best capture the organization’s reason for being. Then he prods them with a series of questions: Who benefits from the organization’s work, and what sets it apart from other animal-focused nonprofits? What are the organization’s overarching goals, and how would the world be different if it achieved everything it wanted?

These thought exercises produce the building blocks for the organization’s mission statement (a brief expression of what your organization does and why), which is often supplemented with a vision statement (the change you want to see in the world) and a statement of core values (how you operate, typically focused on concepts like “collaboration” and “respect”).

“Disputes over what the mission and purpose of the group is ... tend to create fractures in groups."

—Bonney Brown, Humane Network

While you may have thought of a mission statement as simply a marketing tool—a way of introducing your group to the community and potential supporters— a well-crafted one will also serve as an organizational touchstone, says Tholen. “It aligns your resources, focuses your efforts and prevents you from wandering off to things that don’t really fulfill your mission.”

And since intragroup conflict can consume an enormous amount of time and emotional energy, just the process of creating a mission statement can lessen your workload by nudging everyone to home in on a common purpose, says Bonney Brown, president and principal consultant of Humane Network.

Disputes over a group’s purpose and whether the group has lost sight of its mission are among the top reasons organizations fracture and fall apart, Brown says. One disagreement leads to another, and before you know it, one group has splintered into three.

Planning your path

Alice: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

A mission statement by itself won’t keep you from going astray, but it’s a solid starting point for another essential for reality-based rescue operations: a strategic plan.

In its simplest form, this is a document setting forth your group’s goals for the near future (typically three years) and detailing how they will be achieved.

Many people are intimidated by the idea of strategic planning, Brown says. “They’re sure it has to take six months, but it really can be quite simple when you think about it.” For smaller organizations, the final document can be just a few pages that guide your efforts and “help people understand the decisions that get made and why.”

“You need someone not involved in the organization who asks the right questions.”

—Dana Andresen, Feline Rescue

That said, strategic planning can be an emotionally charged process. You may be looking at cutting or scaling back programs that aren’t central to your mission or that you simply lack the funds and people power to maintain. “It’s very hard, because it’s always someone’s pet project,” Brown says.

Dana Andresen found herself in that exact situation in 2017, a year after she joined Feline Rescue in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Founded as an all-volunteer organization, the group had operated a small shelter and foster care program for nearly two decades. “There was some serious mission creep,” says Andresen, who was hired as the organization’s first paid executive director. A variety of side programs and a hodgepodge of processes were detracting from the group’s core goals. At the same time, some longtime volunteers were resistant to change, leading to some “really vicious, nasty exchanges.”

The group hired a business consultant with a background in strategic planning to survey staff and volunteers, moderate discussions and help formulate a way forward. Today, the organization has nine paid staffers, including a veterinarian, and is positioned to help more cats while maintaining high standards of care in its shelter and foster programs, Andresen says.

In Andresen’s mind, having an outside perspective was essential to getting the organization back on track and setting the stage for growth. “Smaller groups will try to do strategic planning on their own, but it’s so difficult to stay objective. You need someone not involved in the organization who asks the right questions.”

Brown agrees. By the time an organization realizes it has lost its way, relationships among board members and other stakeholders are often strained at best. “I often feel more like a marriage counselor,” she says, and in this environment, it’s especially important that anyone leading the planning process be viewed as a neutral party.

If your budget doesn’t allow you to hire a consultant, your local or state nonprofit center may be able to connect you with a qualified professional willing to do it for free. You can also look for a volunteer among local business leaders, who are often well-versed in strategic planning.

The important thing, says Brown, is to find someone whom “everyone agrees they’ll defer to as an expert.”

Right-sizing your goals

“It sounded an excellent plan, no doubt, and very simply and neatly arranged; the only difficulty was, that she had not the smallest idea how to set about it.”

As your organization embarks on the strategic planning process, it’s important to keep in mind that you’re not drafting a dream list of all the programs you’d love to bring to your community.

“Specific, measurable and attainable” are common bywords in the numerous books and articles devoted to strategic goal setting. Determining which goals meet those criteria requires a clear-eyed examination of your organization’s strengths and weaknesses.

Are you keeping records of animals helped, returning calls and emails within a reasonable time, thanking donors, supporting volunteers, filing legal documents, paying bills on time, updating your website and accomplishing all the myriad tasks necessary to running an effective nonprofit?

For organizations that are struggling with the basics, Brown recommends a plan focused on capacity building. That doesn’t just mean crafting a solid fundraising strategy, but also ensuring you have the right people and processes in place to support your current operations so that you can one day progress toward bigger goals.

Many rescue groups and their core members operate in a near constant state of chaos simply because they’re “unable to recognize the necessity of engaging people in the group other than those who want to do direct animal rescue,” Brown says. But there are people who love the behind-the-scenes work, from fundraising to filing: “You just have to value them and be willing to find them and engage them.”

A strategic plan focused on recruiting people to fill specific gaps in your operations may not feel as inspiring as launching new services, but it will alleviate the pressures on your team and enable everyone to work based on their strengths and interests.

If the free spirits among your team balk at the idea of being confined by a three-year template, emphasize that a strategic plan can be “a living, breathing document,” one that your organization will revisit at least once a year, says Harvey.

“Nobody should singlehandedly be able to say, ‘Yeah, I don’t care what’s in the plan; I’m going to do these other things,’” she adds. “But has an amazing opportunity come up that we can’t say no to or don’t want to say no to?” If so, and your board agrees it’s more important than something in the strategic plan, you can simply do some reprioritizing.

In this way, a strategic plan can be flexible while also imposing some discipline and preventing your organization from exceeding its capacity, says Lisa LaFontaine, CEO of the Humane Rescue Alliance in Washington, D.C. “You can only say yes to something new if you go back to the strategic plan and amend it. You can’t just keep adding.”

“You can only say yes to something new if you go back to the strategic plan and amend it. You can’t just keep adding.”

—Lisa LaFontaine, Humane Rescue Alliance

Saying no, for now

Door: “Why it’s simply impassible!”

Alice: “Why, don’t you mean impossible?”

Door: “No, I do mean impassible.” (chuckles) “Nothing’s impossible!”

Setting priorities, sticking to a plan, being proactive, working within your capacity, living your mission—these are common catchphrases in the nonprofit world.

How they often play out in real life is in the act of saying no. No to intervening in certain situations, no to launching new programs, no to bending to outsiders’ opinions of what your group should be doing.

And in animal rescue, saying no isn’t easy. “We all suffer every time we have to say, ‘We can’t do that; we can’t help with that right now.’ It’s a horrible position to be in,” Harvey says. Yet “the groups that can do that are the groups that have been the most successful and long lived: the groups that know who they are and don’t try to be everything to everyone.”

After all, Harvey points out, even with 90 staff members and more than 1,000 active volunteers, the Cleveland Animal Protective League can’t address animal suffering and homelessness from every angle. Its core programs include running a shelter; conducting humane investigations; and operating an animal welfare clinic, a trap-neuter-return program and a community outreach program that provides pet care services to low-income Cleveland residents. Yet occasionally someone will ask why the organization doesn’t have a humane education program for local schoolchildren.

“I sit down with the person and explain that, ‘Yes, what you’re suggesting is amazing and wonderful, but our current facility won’t allow us to execute a program that would have a high impact,’” Harvey says. She pulls out a copy of the strategic plan and explains that the organization has selected the programs it believes will have the biggest lifesaving impact and is operating at full capacity; to go off track and launch another initiative would require taking resources away from one of those programs.

“You have to stay the course, keep yourself on track, and then you set yourself up to be as effective as you can.”

—Sharon Harvey, Cleveland Animal Protective League

Rejecting a proposal for a worthy project or a request for assistance can feel demoralizing, but it helps to remember that a “no” today doesn’t mean “not ever.” In fact, Harvey foresees a time when her shelter will have a humane education program; it will just take time to increase the organization’s capacity and improve its facility.

“As you say no in order to remain focused on your larger strategy, you get to a day where you can say yes to those worthy projects,” she says. “You have to stay the course, keep yourself on track, and then you will set yourself up to be as effective as you can.”