Protecting the protectors

Safety protocols for rescues are critical—for both people and animals

In October 2016, rescue efforts were winding down after Hurricane Matthew thrashed the coastal Southeast. Animal rescuers had gathered for a debrief on the efforts to help stranded pets amidst the widespread flooding, washed-out roads and power outages.

Mark Balestra remembers the session well, because it provided a reminder of how things can go wrong when inexperienced animal rescuers, with the best of intentions, prioritize helping animals over their own safety. One county over, a rescuer had gone into high water wearing jeans, recalls Balestra, division director with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Animal Care and Control in North Carolina. “She had no gear, no waders, no nothing.” The water was cold, and the woman soon began showing signs of hypothermia. “They were forced to abandon the mission to get her to safety.”

Making sure responders are safe— trained, equipped and supported in the field—is critical not just for them, but for the overall mission. In a disaster situation, even minor injuries can have major consequences, says John Peaveler, administrative lieutenant of emergency services for the San Diego Humane Society. “Any time that somebody’s no longer able to work, it takes more than one person out of work. Someone has to drive them to the hospital or stay with them to help them recover,” he says. “The loss of one person is always the loss of at least two people. Sometimes it means stopping the mission entirely and focusing on that person.”

“The loss of one person is always the loss of at least two people. Sometimes it means stopping the mission entirely and focusing on that person.”

—John Peaveler, San Diego Humane Society

Having safety protocols in place not only helps secure the success of the mission, it builds responders’ confidence and lets them know their well-being is important. Plus, animal responders who work within the broader incident command system and have clear safety protocols in place are likely to get more respect from other emergency responders—which in turn may increase those agencies’ willingness to prioritize animal needs and work with you to achieve your goals, during this response and the next.

At the end of the day, says Sára Varsa, vice president of the Humane Society of the United States Animal Rescue Team, “if you don’t take care of your workforce, they can’t take care of the animals.”

What you don't know can hurt you

Whether saving animals from floods and fires or removing them from hoarding situations and puppy mills, animal rescuers deal with health and safety challenges that can run the gamut: Lifting heavy objects and animals. Wading through freezing floodwaters rife with invisible currents. Breathing toxic air. Combing through response sites that may be littered with rusted metal cages or encrusted with feces carrying pathogens from unvaccinated animals. Working hours that can exhaust them, body and mind.

And then there are dangers from the animals they’re there to help. In largescale responses, “it’s not just [a matter of] going to rescue one dog trapped in a well,” says Varsa. “It’s going to get 60 dogs, in substandard conditions, who have been suffering for a long time and likely haven’t had much human interaction, and at best are going to be in fight-or-flight mode.”

The best way to keep responders safe in the field is to make sure they have the knowledge and skills necessary to do the work at hand. That means knowing as much as possible about the conditions to expect in any particular situation, but also doing the advance work so that your team has the training and equipment they need.

It’s also helpful for veteran responders to acknowledge how difficult disaster response is and the toll it can take, says Debby MacDonald, director of statewide response for the Michigan Humane Society. Creating a culture where that’s understood can help cut down on people’s tendency to tough it out well past their breaking points.

“Share how you expect it to affect you physically, instead of trying to maintain that sort of ‘veteran tough guy’ presence. That’s not safe for your newer team members,” says MacDonald.

Major responses require personal fortitude, and everyone wants to be a team player in high-stress situations. But “for a lot of people, the first time in a disaster is overwhelming. … You see a lawn chair up in a tree, you see all sorts of things that you haven’t seen before, so you’re focused on all these new things along with the mission. It’s exhausting,” MacDonald says. “You want to set up a culture where it’s OK to say, ‘I’m tired, I need to take a break.’ It’s important to talk about that up front.”

“Share how you expect it to affect you physically, instead of trying to maintain that sort of ‘veteran tough guy’ presence. That’s not safe for your newer team members.”

—Debby MacDonald, Michigan Humane Society

Many veteran rescuers have seen a sort of hero syndrome kick in during major responses, a combination of compassion and ego that makes some people want to do the most dramatic work, regardless of whether they have the background and training to do it.

That’s not only dangerous, but impractical, says Peaveler: “Not everyone can do the coolest, most dangerous parts. There are a lot of pieces [to a response], and you need to train to whatever standard is reasonable for the organization. If what you can do is provide emergency sheltering support for a 10-day period post-disaster, train to that standard—but do that in advance. Don’t do it like, ‘Oh my god, there’s been an emergency. Let’s go and do this thing we’ve never done or thought about doing before.’”

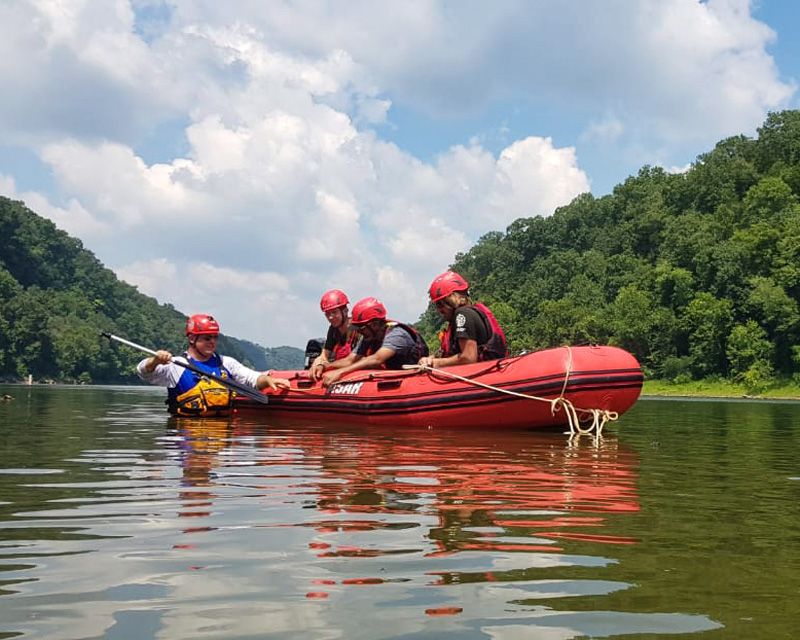

Training for large-scale responses should start well before any response is needed. Even if (knock on wood) your staff members never end up responding to a major disaster, training and preparation will not be wasted time. Balestra recommends drafting and implementing standard operating procedures for most tasks performed in the shelter and the field. Having SOPs in place, he says, means you can rely on them when you need them, whether you’re dealing with an emergency or just a routine call for service. Charlotte- Mecklenburg Animal Care and Control, where Balestra works, has some 90 specific SOPs in place, specifying the protocols for everything from handling aggressive animals to conducting a safe swift-water rescue and building portable corrals for livestock.

While you can’t prepare for every possible scenario, he says, you can ensure that your team members are trained to safely handle the most common field situations. Having protocols in place also helps foster a safety mindset—one that reminds team members they shouldn’t be in a boat if they don’t have swift-water rescue training or attempting to handle a dangerous animal if they don’t have the proper equipment or expertise. Asking people who have never performed a task to do it in a crisis situation is asking for injuries (and possibly lawsuits).

Ensure that your team members are trained to safely handle the most common field situations. Asking people who have never performed a task to do it in a crisis situation is asking for injuries.

Bypass situations where team members may be tempted to “wing it” by keeping a list of contacts you can call when a situation is beyond your team’s expertise. Balestra’s agency, for example, serves a region that occasionally generates calls about alligators and venomous snakes. “Imagine going into some sort of mandatory disaster evacuation and having to remove those types of animals. These can be really dangerous situations,” he says. But if you’ve done your prep work, you won’t have to endanger your staff and will have a list of people to call.

Wanda Merling, deputy director of operations for the HSUS Animal Rescue Team, suggests doing drill exercises on a regular basis to prepare your team. “The more that you do drills and the more you do response, the better you get,” she says. “You learn from each experience.” Debriefings after drills and actual responses also help. “That’s when you go over things that you need to do differently or better the next time and things that you need to add to the equipment and supply list.”

FYI on the ICS

During a major disaster response involving multiple agencies, the most important thing responders will need to keep themselves and others safe isn’t a hazmat suit or training in handling fractious dogs—it’s a thorough understanding of the incident command system. ICS is a management tool frequently implemented during emergency response situations to help multiple groups communicate, coordinate and establish a clear decision-making process.

Many of those who were in the field during the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 can recite chapter and verse about the dangers of animal rescuers with no training in (or even awareness of) ICS protocols. Animal lovers from around the country—trained and untrained—self-deployed to the Gulf Coast. Operating outside official channels, some volunteer responders went about rescuing and transporting animals—even as those animals’ owners were reaching out to the “official” emergency shelters and coming up empty-handed in their search for their beloved pets. Untrained and unequipped volunteers were also wandering in areas full of floodwaters, mold, hazardous waste, unstable buildings and roaming, traumatized animals.

People working outside the ICS can create more problems than solutions for emergency responders. “For safety reasons, emergency managers need to know who is operating in the area, because they need to know that people are professional, trained responders and are going to be safe,” says Peaveler. In disaster situations, law enforcement can end up “wasting a lot of time chasing down a lot of people who don’t belong there and aren’t trained to the right standard.”

The potential for animal lovers with good intentions to endanger themselves and inadvertently create a secondary disaster is the reason that any volunteers for the HSUS Animal Rescue Team are required to undergo ICS training before volunteering. Varsa considers it one of the most important safety protocols. “ICS is really simple: It’s keeping everybody safe, it’s knowing what all the parts are doing, and it’s bringing them into the central command structure so that whoever is in charge can make appropriate decisions,” she says.

Some of those decisions are about staff safety and well-being, a component of field response that should be appropriately addressed when the ICS is well-managed and operational. Team members should be assigned according to their strengths and skills—and should also be trained to know when they’ve reached their limits. An onsite leader needs to oversee the operation and make sure everyone’s needs are being met, such as staying hydrated and taking food and rest breaks. The leader should be able to identify the signs of heat stroke, hypothermia and extreme fatigue, and know what to do to get help if needed.

“People care is the product of leadership and having clearly assigned roles,” Peaveler points out. “Field-level leadership isn’t just responsible for mission accomplishment; it’s responsible for personnel management. … You may need to have multiple people, such as one person who’s much more mission-focused and one person who’s much more logistics-focused. But it needs to be clear that that’s somebody’s job.”

Best-laid plans

MacDonald says she always brings a stock of over-the-counter meds (including pain relievers, antacids and anti-diarrheals), bug spray, and extra gloves and sweatshirts in case someone needs a change of clothes— and lets people know where they are should they need them. Veteran responders usually come prepared, she says, but when an operation includes newer responders and volunteers, they may not have the training or awareness to plan for all the situations that arise and may be hesitant to ask for help.

Even with good planning and training in place, accidents can happen—and when they do, it’s critical to follow the protocols for reporting injuries and getting treatment. Gillian Deegan, assistant commonwealth attorney in Botetourt County, Virginia, remembers a close call she had during a severe neglect case in a neighboring jurisdiction. She was bitten by one of the dogs who’d been seized, but she didn’t report it because she didn’t want the dog to be deemed a biter just because of fear.

A few days later, she received a call that the dog had died, and she eventually learned the dog had tested positive for rabies. Luckily, she still had enough time for the rabies treatment series. “To me, this really hammered home that you need to report any sort of injury in the field,” Deegan says.

Going into the field, the HSUS Animal Rescue Team prepares for the worst. The team is well-trained, and injuries are rare—but Varsa knows a safety net makes sense. “Prior to a rescue, we talk with the lead agency to ensure emergency responders or fire service has been notified,” Varsa says. Even if they aren’t on scene, “they’re on call and know where we are.” Another thing to consider is how people will get in and out of the site, in case someone has a critical emergency, “so there is a way to transport that person to a place for the necessary medical attention.”

Even operations that have been planned for months in advance can and will offer surprises: The puppy mill ends up having twice as many dogs as estimated. The cat hoarding case turns into a cat-goat-horse-chicken rescue. The wind turns and the fire changes direction toward the site where your team is working. Emergency animal response needs people who are compassionate, but also trained, equipped and well-managed—and prepared to follow directions and be flexible when they need to be.

“Animal rescuers are really good at sacrificing themselves on behalf of animals. It’s our passion; it’s the driving force that’s what makes us the amazing people we are,” says Peaveler. “But it has consequences as well.” Putting safety protocols in place well in advance helps ensure that dedicated responders can focus on their mission: getting animals out of harm’s way.