Seeds of support

Nurturing relationships with major donors can help grow your organization

Take a look at your donor list, and you’ll likely see evidence that love for animals crosses all socioeconomic lines. There’s the senior on a fixed income who pledges $5 a month, and the local business owner who donated $1,000 during your last end-of-year fundraising drive.

You might assume that each of your donors is giving as much as she can to your cause. But behind some of those small and medium-size checks are animal-loving people who could and would give major gifts of money if only you got to know them.

Major gift fundraising is “a bit of an art form and a relationship-building process,” says Kimberlee Dinn, senior director of institutional giving and stewardship at Humane World for Animals. The effort is worth it, because major gifts can fund lifesaving programs that other donations can’t support. Plus, once you acquire major donors, you’ll have a head start when you need to fundraise for an expensive project, like building a new shelter.

Major gifts have “the ability to change the trajectory of the organization,” says Dan Reed, CEO and co-founder of fundraising training company Seed and former chief development officer at Morris Animal Foundation. “You’re probably not going to take these big, transformational steps in your program without the significant generosity that [comes from] major gift relationships.”

Research and cultivation

What an organization considers a major gift will depend on its size and resources, but Reed recommends that small organizations define a donation of $5,000 or more as major.

In his experience, about 3 to 5 percent of an organization’s total donor base is capable of giving a major gift.

“So many organizations do not have a clue how much is actually at their fingertips,” Reed says.

A person’s likelihood to give depends on their capacity (wealth) and propensity (likelihood to give, which increases if they’ve given charitably before, especially to your organization or a similar one). To find major gift prospects, look at who has already been donating to you for a long time and might have a larger capacity to give, says Dinn.

A variety of software exists for prospect research, including WealthEngine, FoundationSearch and Foundation Directory Online, Dinn notes. But for smaller organizations that can’t afford those tools, Google is sufficient, says Reed.

“It’s really looking and saying, ‘OK, this person has some wealth, and yes, they’ve given to a few organizations,’” says Reed. Someone who has donated to animal causes before is a better prospect, but it doesn’t hurt to look for people who have given to other types of organizations.

You can also look in the business section of your local paper to see who the “movers and shakers” are, because they could be potential donors, says Rob Blizard, executive director of the Norfolk SPCA in Virginia.

“The key here for small organizations [is]: Do not spend too much time finding the bull’s-eye prospect,” Reed says. “Find prospects on the dartboard.”

Blizard suggests periodically calling people who give multiple small donations each year. “In a way they’re sending a signal to you that ‘I’m really interested in what you’re doing,’” he says. “Maybe they’ll give at a higher level if you pay them a little attention.”

Other resources are your board of directors, committee members or volunteers, especially when you consider the fundraising adage that “people give to people and not to causes,” says Jim Tedford, president and CEO of the Society of Animal Welfare Administrators.

“Oftentimes those folks have got really incredible community connections that you as a CEO may or may not have,” he says.

“Some board members will feel comfortable being an active part of [fundraising]; my experience is that most board members do not feel comfortable with that,” says Blizard. But they could help open the door to meetings with potential donors they know, suggest donors or even have some insight into certain people’s capacity to give.

Relationships that blossom

The average time it takes to develop a relationship with a person before you ask for a major gift is 18 months, says Katherine Shenar, chief of staff at the San Diego Humane Society. For someone to give, they “have to feel confident about the relationship” with the fundraiser, and the fundraiser needs to develop a “rapport and friendship with these donors,” she says.

Whether you’re working with prospective or existing donors, relationship building will include getting to know their interests, keeping them updated on your work and, if they’ve given before, letting them know how their generosity has made a difference.

In this type of fundraising, the key is to get donors or prospects to share personal stories about their interest in the cause, says Reed. When people share their stories, it triggers an emotional investment in your work and allows fundraisers to know what truly matters to the donors.

To facilitate this storytelling, fundraisers should share a personal story of their own that shows why they care about the cause, says Reed.

He also recommends that fundraisers learn “active listening” skills, which allows them to fully concentrate on what potential donors are saying, rather than just passively hearing them.

Dinn says her rule of thumb for conversing with donors or prospects is to let them talk two-thirds of the time.

“Have a series of good, solid questions you want to know about them,” she says. “… You want to have a conversation with them and find out what motivates them and what they are excited about in your work, and from there you can open up the conversation a little bit more.”

Part of building a relationship also involves knowing how often a donor wants to hear from you. You shouldn’t ask for a gift every time you contact a donor, but you should consider every interaction a step toward a future ask.

“It’s really a matter of customizing that based on the individual donor and what their interests are and what their tolerance level is for that,” says Tedford. “There’s a very real concern about donor fatigue if you are in contact too frequently. At the same time, you don’t want to be out of sight and out of mind.”

As a guideline, Reed recommends contacting a donor at least four times a year, but six times is ideal.

Not all of these interactions have to be face-to-face, like lunch or coffee meetings. They can include phone calls or personalized emails or letters, depending on the method the donor prefers.

Think of communication with donors as similar to “all the little things … that we put on our calendars for our grandmas,” says Reed—birthday cards, a note with good news or a phone call with some updates.

For example, if a donor is interested in community cats and your organization gets a grant for a trap-neuter-return project, call her or send her a link to an article about it, says Blizard.

Especially if you have a small organization, it can be difficult to find the time for donor outreach, but try to pick five donors to call each week, says Marta Diffen, director of development at the Dumb Friends League in Denver. “It’s such a critical component to the organization, to the animals that are in your care, to be able to go back to the people that have been supporting you [and] let them know that they made a difference.”

Besides, today’s technology makes it easy to communicate with donors without taking too much time out of your day. Videos of the animals in your shelter can connect donors to the work they support. Or, just a video of you saying thanks to a donor (not necessarily including animals) can help foster the personal connection you’ve established, says Reed.

“When you’re in the middle of your day and a donor pops up in your mind, literally just take your iPhone out and just do a little video,” says Reed. It doesn’t have to be perfect—just email it to the donor.

You can also use Facebook to communicate on a personal level with individual donors.

“I am friends with donors on my Facebook page,” says Shenar. “We share information, put things on their walls. It’s a great way to connect with people.”

And keep in mind that many of your donors are likely following your organization’s progress via its own Facebook page and other social media channels.

“If your Facebook page is not active, and you’re not featuring lifesaving moments or extraordinary stories of how you’re helping animals, you’re missing the opportunity to connect with donors,” says Shenar.

Careful tending

Ideally, once you receive a gift, you’ll continue all the contact with your donor that helped secure the money in the first place. But post-gift, you’ll want to do two basic things, if nothing else: Send an acknowledgment letter thanking the donor “quickly and efficiently” (the national average is within 72 hours of receiving the gift), and report to the donor after the gift is used, says Angela Joens, assistant vice chancellor of development outreach at UC Davis.

Multiple thank-yous over time, especially from different people (like from the executive director and board chair) can’t hurt as long as you personalize them to the donor, says Reed. Later, report back to the donor with a brief one-pager that outlines what the gift allowed you to do, says Dinn.

“I think the No. 1 thing that you can do is to make sure the donor is aware of the impact of their gift,” says Dinn. “… They’re so much more compelled to give, and give more, when they feel appreciated and when they feel that ‘Wow, I did a good thing here.’”

Other ways to make donors feel appreciated include events and recognition. Recognize them in an annual report, on your website, on plaques hanging in the shelter or on engraved stones on the sidewalk outside your building. At Norfolk SPCA, donors’ names can be displayed on kennels if they give a certain amount for 12 months, says Blizard.

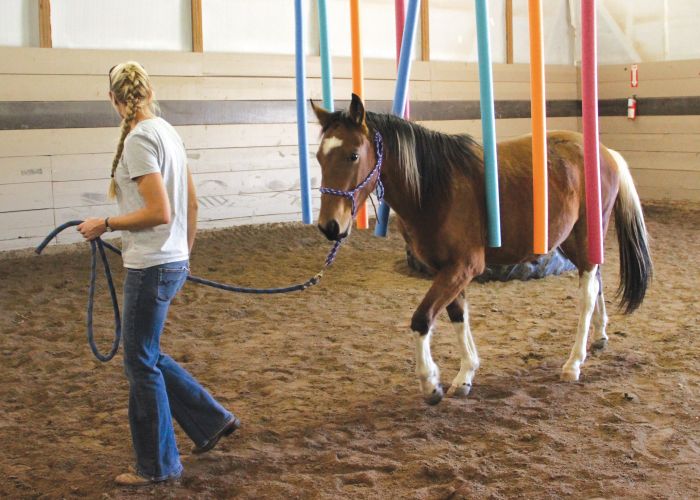

If you’re having an appreciation event, the group’s mission needs to be “the centerpiece of what the party involves,” says Shenar. Even if you’re having a cocktail party at a private home, make sure shelter animals are there, she says.

Some supporters might prefer sophisticated events like the Dumb Friends League’s reception at the Denver Art Museum, and others might feel more comfortable attending a shelter tour for donors.

“Your goal at any donor appreciation event is for them … on the drive home [to] say to their spouse, ‘Wow, I love that organization. I’m so glad we donate to them. I can’t wait to see what we’re going to do … the next time we make a gift,’” says Shenar. “You want them to feel appreciated, valued and inspired to make another gift.”

Norfolk SPCA invites major donors, along with the mayor, city council, board members, shelter staff and key volunteers, to a reception every December at the shelter. The event includes a shelter tour and opportunity to visit the animals, and donors also receive statistics and information about the shelter’s accomplishments that year.

“It’s a way of saying thank you and being accountable to them,” says Blizard. It also encourages many donors to give a significant gift before the year ends, he adds.

At UC Davis, donors like events that get them involved—like helping with the harvest at the campus vineyard, says Joens.

“If you can touch it, feel it, smell it—that’s the best,” she adds.

At San Diego Humane Society, a notable donor appreciation event was a behind-the-scenes tour of the kitten nursery, says Shenar. “Again, if they can see your mission in action and they can actually see the work being done, it’s very powerful.”

Overall, there’s no set formula for having good relationships with donors. “There are fundamental things you have to do,” like thanking them after you get a gift, says Joens, “but how you do it, what it looks like, what it sounds like, that’s all based on knowing your audience.”

And if you want to be sure you know them, when you meet a donor, ask these three questions, she says: Why do you give to this organization? What could we do to show our appreciation? What would inspire you to give again?