The virtues of virtual training

Behavioral support services shift online, creating challenges and opportunities

When COVID-19 restrictions were first enacted this past spring, animal behavior analyst Terri Bright expected a short-lived disruption in services.

“We figured we would stop for two or three weeks,” says Bright, who serves as the director of behavior services for the Massachusetts SPCA-Angell Animal Medical Center, which is headquartered in Boston. Having served roughly 90,000 clients in 2019, Angell is easily one of the busiest veterinary hospitals in the country. Bright’s behavior services department serves both the medical center and the shelter. Pre-COVID-19, it saw 700 to 800 clients a year at the medical center for individual behavior consultations, and offered as many as 50 group classes each week at MSPCA facilities, including puppy training, agility and obedience classes.

After three weeks came and went, it became apparent to Bright that she and her team would have to come up with another way to serve their community. “People were desperate for behavior classes and some sort of support,” says Bright. She and her staff moved quickly, becoming adept at video technology and Zoom to create a series of videos and handouts and offer live trainer consultations to replace in-person behavior classes.

Across the country, animal trainers and behaviorists like Bright are part of a surge in distance support services, including phone and video consults and online classes. In many cases, virtual support has some surprising benefits. However, for many, the learning curve is steep, and the animal welfare community at large has much to learn from the successes and failures of those at the forefront.

“People were desperate for behavior classes and some sort of support.”

—Terri Bright, Massachusetts SPCA-Angell Animal Medical Center

Awaiting instructions

Through the spring and summer, shelters and rescues across the country reported increased numbers of animals in foster homes (including an incredible 720% spike early in the pandemic). Many foster volunteers were first-timers, and they, along with recent adopters and people who were stuck at home and perhaps more likely to notice concerning behaviors in their pets, increased the demand for behavioral support just as in-person obedience and agility classes and one-on-one consults were canceled.

This left trainers and other behavioral experts scrambling to switch to distance support. While it hasn’t been all smooth sailing, many are reporting surprisingly positive results.

“We kept thinking ‘This will come back,’” Mailey McLaughlin says of the six in-person classes she used to teach every week at Atlanta Humane Society. When the shelter went into lockdown in March, McLaughlin, who has spent more than two decades working as a trainer, was teaching several obedience classes and had a full roster of in-person private lessons. So she switched to the shelter’s web conferencing platform, conducting classes from her living room and using her dog for demonstrations. The shelter also created a behavior hotline, offering both adopters and other pet owners in the community the opportunity to sign up for 40-minute phone consultations. Meanwhile, the shelter’s foster coordinator fielded basic behavioral questions from foster families.

As the pandemic continued, the hotline spots filled up and kept filling. McLaughlin realized that the quick-fix live calls she had started doing through the shelter’s web conferencing platform weren’t going to cut it in the long term: She would have to become a full-fledged virtual trainer.

720% more pets were in foster care early in the pandemic.

Learning on the go

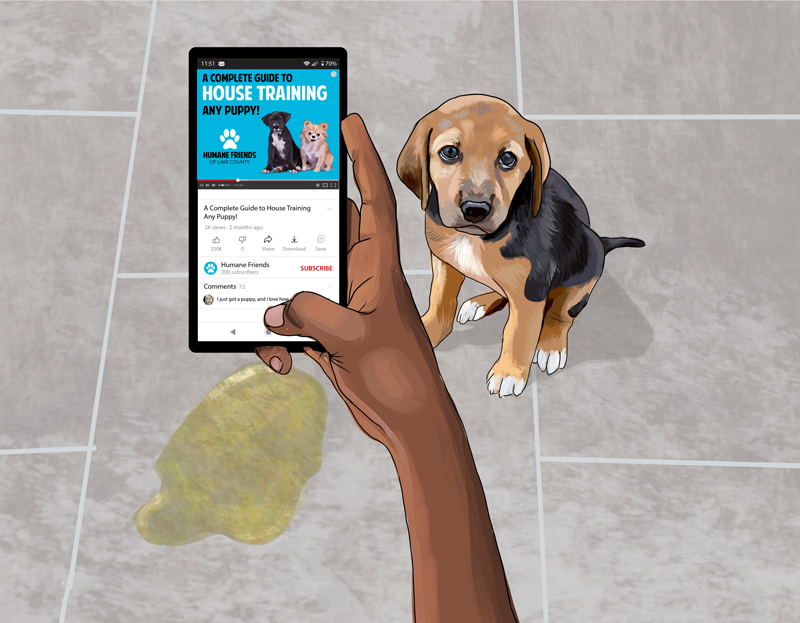

Bright’s team reached the same conclusion, leading them to make a series of YouTube videos on topics ranging from how to put a harness on a dog and beginner obedience to a “puppy home start” program. Those who signed up for classes received access to the videos, a series of instructional handouts and three Zoom appointments with one of MSPCA’s trainers.

Then Bright and her staff started looking at applications that people submitted for behavioral support and “tried imagining which could be handled via Zoom,” she says. As it turned out, 99% of the consults could be done remotely, and the team started virtual behavioral visits in April. For people who were reluctant to try the new format or had technological challenges, those appointments were handled via a good old-fashioned phone call, which Bright says worked just fine, considering that much of the consultation process involves asking expanding and clarifying questions to create an assessment. For Zoom calls, from the comfort of her living room, Bright could use her trusty canine assistant, Ribbon, to demonstrate behavioral interventions for dogs. By summer, the team was back to helping as many clients as they had before the pandemic.

For McLaughlin, progress was more incremental. One challenge she faced was that her own dogs followed the commands too easily to make for good demos. So she went out and made a series of videos on topics such as basic leash training using some of the greener shelter dogs, along with a friend who had a dog in training. She added narration to the videos, then incorporated them into the live webinar so participants could view realistic scenarios.

McLaughlin’s next enhancement was to assign her human students homework; each week, they would send her an unedited video of their dogs performing specified tasks. When McLaughlin spotted common errors among the clips, she would show them, with the students’ permission, to the class in the next live webinar.

She discovered that the virtual format also solved a variety of access challenges for students, such as distance, reliable transportation or having to care for kids.

Once July rolled around and in-person classes were again postponed, McLaughlin initiated her next round of changes. Rather than have live webinars during a regular weekly time slot, she prerecorded them. McLaughlin was no longer tied to a live schedule, plus students could access the videos when and as many times as they wanted. McLaughlin also created a Facebook group for students where they could ask questions, post additional videos and chat with their classmates.

Going the distance

Like the urgent implementation of veterinary telemedicine during the pandemic, the sudden shift to virtual behavioral care is just a quicker way for the animal rescue world to get where it was headed anyway, says Lindsay Hamrick, director of shelter outreach and engagement for the Humane Society of the United States.

“Over time, what we’ve seen is a staffing model at animal shelters that shifts people from receiving animal care at the building to being more available to the community’s needs. COVID sped that right up,” says Hamrick.

“I was resistant [to online training] in the beginning. I’ve absolutely changed my view on that now.”

—Mailey McLaughlin, Atlanta Humane Society

“Over time, what we’ve seen is a staffing model at animal shelters that shifts people from receiving animal care at the building to being more available to the community’s needs. COVID sped that right up,” says Hamrick. Hamrick, who is also a certified professional dog trainer, says the pandemic is revealing to shelters and rescues how vast the need is for behavioral support, along with new ways to provide it.

The need isn’t limited to dogs.

“With so many people spending more time at home with their cats, there has been a surge of cat behavior webinars this year, from kitten socialization to how to clicker train your cat,” says Danielle Bays, senior analyst for cat protection and policy at the HSUS. “Everyone was doing a webinar this spring.” Cat behavioral support programs have long relied on virtual counseling, Bays adds, so frustrated cat owners and foster caregivers seeking answers to litterbox problems, aggression between cats and other issues haven’t had to adapt in the same way as dog owners.

“Behavior always seems to follow veterinary medicine,” says Hamrick, who likens current conversations about behavioral support to those within the last two decades about how to offer low-cost spay/ neuter to the public. “Trainer referrals can be expensive, just like with private spay/ neuter.” Just as many private veterinarians now partner with nonprofits to offer free or low-cost spay/neuter, Hamrick would like to see expanded partnerships with private trainers to offer services for some of the most vulnerable owners and their pets.

With easy-to-access behavioral support, whether from private trainers or shelter and rescue staff, more people would be willing to foster, Hamrick believes. Additionally, such programs could provide a safety net for pets who otherwise might be surrendered. “Classically, we wait for someone to be ready to surrender before providing behavioral advice, because that’s when they’re reaching out to us,” but by then it may be too little, too late, and the human-animal bond may already be broken, Hamrick says. “But if you are promoting behavioral support in an ongoing way, it won’t become a last-ditch effort.” And with so much behavioral support already shifting online, in some ways those services will be easier to provide than ever.

“Classically, we wait for someone to be ready to surrender before providing behavioral advice, because that’s when they’re reaching out to us. But if you are promoting behavioral support in an ongoing way, it won’t become a last-ditch effort.”

—Lindsay Hamrick, The Humane Society of the United States

Lifesaving lessons

“I was resistant [to online training] in the beginning. I’ve absolutely changed my view on that now,” says McLaughlin, who is quick to extol the virtues of virtual training. The numbers support her new perspective. When she first started virtual classes in the spring, McLaughlin had only five or six students, whereas her live classes were regularly full at 12 students per session. By July, her online sessions had jumped to 15 participants and growing, numbers that for her are only possible in virtual classes. On the other end, she points out, if a session has only one student, it’s not a loss because all of the material is prerecorded.

Another benefit McLaughlin discovered is that there’s no more shouting—from either her or the students—to be heard over barking dogs. “And if they miss something, they can go back.”

Bright has also found multiple benefits in the virtual model, especially with regard to clinic visits. “The animal likes it because they don’t have to go to the animal hospital. And I don’t have to sit in a small room with an animal that’s aggressive,” she explains. Plus, on video, she can have an owner walk her around their home to identify potential environmental challenges.

“The feedback from clients has been tremendous,” Bright says. The MSPCA is also receiving requests for support from farther away, causing her to speculate that she’s reaching people she may not have otherwise.

Still, virtual visits and classes are not without their challenges. As Bright says, the ability to be with the owner and to walk with them and their dog just doesn’t have a virtual equivalent. Also, technical limitations or Zoom fatigue can create too big of a hurdle for some owners. McLaughlin says that before enrolling people in web-based classes, it’s best to make sure they are capable of using the technology. It’s also important to make sure you understand the technology yourself and have sufficient technical resources to make online services relatively easy for providers and users.

Bright also points out that being able to assess an animal effectively through a virtual visit may rely heavily on the experience level of the trainer or other behavioral expert. Less seasoned trainers or behavioral experts could find it more challenging to assess an animal and the overall situation virtually.

Yet in spite of the challenges, the pros definitely outweigh the cons, Bright says. McLaughlin agrees. “I never would have thought this job would have lent itself so well to virtual interaction,” says McLaughlin, who is certain that come what may with the pandemic, virtual instruction will remain a permanent part of her shelter’s offerings.