The weight of caring

High suicide rates among veterinarians prompt focus on challenges, resources

It was a busy day at the veterinary practice where Dr. Carrie Jurney worked. Jurney, a neurologist, had just been tapped to be the medical director of the practice when she got a call to come to the operating room and assist a team working to save the life of a dog. She recalls with stark clarity the moment the veterinarian’s hands just stopped moving. She looked up at Jurney and said, “If this dog dies, I’m quitting my job, I’m going home, and I’m going to kill myself.”

It was a life-changing moment for Jurney. She’d been aware the fellow veterinarian was struggling—she was in the midst of a divorce and wasn’t handling stress well—but had no idea the situation had become so overwhelming. Jurney and her colleagues ended up reaching out to the woman’s family and her therapist, and with support and over time, she’s doing much better. Still, in that experience something shifted for Jurney, who felt called to take a look at her own well-being. “Her speaking up let me notice that I was not doing well.”

In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control released a study that showed that a trend that had been documented previously is persisting—high suicide rates among veterinarians. According to data covering a 36-year period (1976-2015), male veterinarians are 2.1 times more likely to die by suicide than the overall population, and females are 3.5 times the national average.

While the proportion of female veterinarians who commit suicide has remained stable for nearly two decades, the actual number of deaths has gone up due to the increased ratio of female to male veterinarians—now more than 60 percent are women. An earlier study found that female veterinarians generally have higher rates of risk factors for suicide, including depression, suicidal ideation and previous attempts.

Of those veterinarians who took their lives, 37 percent used pharmaceutical poisoning—often the same or similar drugs used to euthanize animals—as the method; that’s 2.5 times higher than the number of non-vets. What’s behind these numbers, of course, are people and their stories.

Female vets are 3.5x as likely to die from suicide as the general population.

Costs and consequences

One of the highest-profile veterinarian suicides in recent years was that of Dr. Sophia Yin, a world-renowned veterinary behaviorist who died in 2014 at age 48. Yin’s work focused largely on gentle methods to modify complex behavior issues in dogs. Yin was widely recognized, but tens of thousands of U.S. veterinarians labor quietly in private practices and shelters, facing stressors that could prove life-threatening. As a result of her experiences in the clinical setting, Jurney became a founding board member of Not One More Vet, an organization created by veterinarian Dr. Nicole Arthur after Yin’s death drove home the magnitude of the stresses faced by many vets.

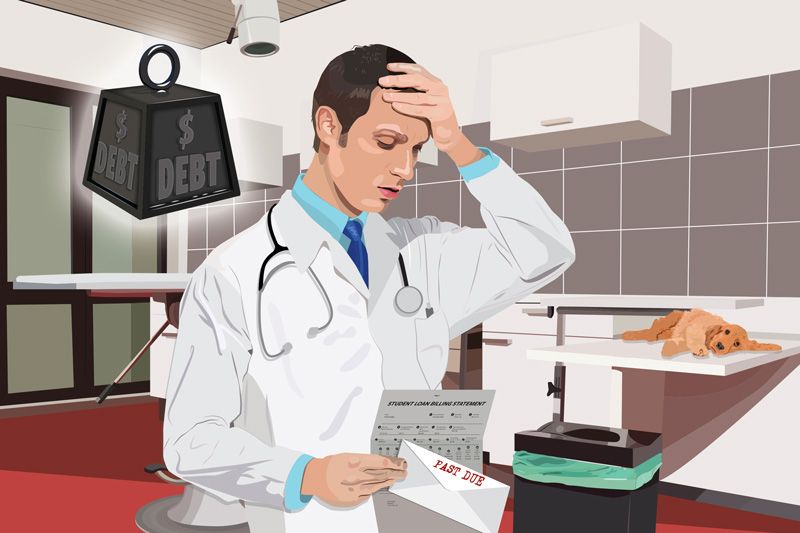

When you talk to veterinarians about stress, money comes up immediately. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, in 2016 the average veterinarian had student loan debt in the neighborhood of $143,000. Total costs for vet school can run as high as $400,000. Doctors at human practices may expect to pay that back relatively quickly, but veterinarians can expect it to take much longer. While an experienced veterinarian has the potential to earn a six-figure salary, according to national statistics, many barely cross that mark. According to job site ZipRecruiter, salaries can vary widely by state. While the average salary in New York is just under $105,000, North Carolina veterinarians average just over $73,000 in annual pay.

The average veterinarian student loan debt in 2016 was $143,000.

Another dimension of the financial equation is their clients’ own access to care. As Jurney explains, veterinarians don’t just deal with their own money concerns: “They’re also dealing with other people’s financial realities.” Over half of veterinarians say they experience cost-related issues daily or multiple times a day, says Dr. Barry Kipperman, board president of the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association. Pet owners often think services for animals should cost less, or they simply don’t have the money to pay for a recommended treatment.

“It’s a metaphorical brick wall because it hurts veterinarians to have to deny care or to compromise the care of animals,” says Kipperman, who adds that this can create “moral stress.” As defined by Kipperman, moral stress is the result of being asked to do something that conflicts with your beliefs. In private practices, Jurney explains, this can include having to do euthanasias in cases where the veterinarian doesn’t believe it’s absolutely necessary.

In shelters, veterinarians are often working with space and resource constraints. They “have to do the best to maximize the adoption of animals in their care, but there are a limited number of cages,” says Kipperman.

One online course for veterinarians describes moral stress like this: When you have regular job stress and take a beach vacation, you come back feeling better. But when you have moral stress, you spend that week on the beach lying there wondering if you did the right thing and ruminating on your potential missteps.

There’s also the unavoidable reality that animals have shorter lifespans, says Dr. Michelle Salob, a staff veterinarian at the Santa Fe Animal Shelter in New Mexico.

For human physicians, “most of the time you see your patients cradle to grave,” she says. For a veterinarian, “it’s like if you had friends dying every day.” As Dr. Jennifer Steketee, veterinarian and executive director of the Santa Fe shelter, says plainly, “It’s exhausting.” And either by training or disposition, veterinarians in some cases may be especially ill-equipped to deal with such stresses.

Driven to help

Several veterinarians point to the general dispositions and motivations of many who choose a veterinary career as potential contributing factors to suicide. All say that more often than not, veterinarians are introverts who, by nature, generally process things internally and may not be as apt to turn outward for help.

Steketee says that in part, veterinarians may suffer from their own training, which is to largely not show their emotions. “It’s rare to find a vet curled up crying in the corner.”

Additionally, many veterinarians have type-A personalities with a strong drive to succeed, meaning they can have an even more difficult time processing the “failure” of not being able to save an animal. Veterinarians have a lower failure rate at suicide attempts, Salob explains, because of both an inherent drive toward efficiency and their training in euthanasia.

Then there are the often-unreasonable expectations placed on veterinarians—and that they might place on themselves. Salob, who has practiced at several shelters around the country, says she’s had experiences where “it never ended. You felt like you could never get ahead of what was happening. You felt guilty when you’d leave, even if you’d been there all day.” She says veterinarians would routinely check on animals multiple times before departing, then continue thinking about the animals after their shift.

The nurturer side of veterinarians can prompt them to try to take it all on, says Erin Wasson, a veterinary social worker at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan, making it hard to maintain emotional equilibrium.

Sadly, most people outside the world of animal medicine have no idea about the tremendous pressure veterinarians are under and are more than willing to criticize them—and often publicly.

Male vets are 2.1x as likely to die from suicide as the general population.

Under attack

In 2014, Dr. Shirley Koshi, a veterinarian in the Bronx, New York, died by suicide after a long and very public custody battle over a sick cat who’d been brought to Koshi’s clinic after he was found in a local park. When the feline started to recover, a woman identifying herself as a rescuer showed up to claim him. Koshi refused to hand over the cat, triggering a bitter battle that included a lawsuit against the veterinarian and a demonstration outside her clinic.

Sadly, veterinary harassment is a familiar story. Sticker shock about the cost of veterinary care, the fact that a veterinarian couldn’t save their animal’s life or a decision by shelter staff to euthanize an animal suffering from a severe medical or behavioral issue, for example, can send irate owners or community members to social media, where they castigate the veterinarian (and often the staff, as well). Part of the challenge, many veterinarians agree, is that people don’t understand both the expense of veterinary medicine and the way it’s practiced—for example, due to the complexities inherent in practicing medicine, it’s impossible to always be certain how a particular test or procedure will come out or a medication will work.

One area that’s not frequently talked about is backbiting within the veterinary community. “Private-practice vets often don’t understand shelter medicine and herd medicine,” says Steketee. As a result, she says, “We are very hypercritical of each other’s work without knowing the background.”

Salob adds that it’s important for private-practice vets to understand how shelter medicine is practiced because “that’s where their patients are coming from.” Steketee says there’s sometimes a stigma around shelter veterinarians because there can be a perception that shelters “are where bad vets go.” That kind of criticism would be hard on anyone.

Additionally, people often have unrealistic expectations of veterinarians. “The public expects us to be saints,” always available and always willing to treat animals for a reduced rate, says Steketee. “I was once screamed at by a woman to come to her home to euthanize her old dog and bring the body back to the shelter and cremate it for free.”

Given all of these pressures and the fact that veterinarians are regularly confronted with animal suffering and death, says Salob, suicide “could start to become a somewhat rational-seeming idea.” Steketee agrees, saying it’s a complex issue with multiple causes, so solutions, too, must be multifaceted.

Some say veterinarian suicides could be limited by better controlling medications, such as instituting a multi-signature system to access euthanasia drugs. While such protocols could prove helpful, Salob points out that with their medical credentials, veterinarians wouldn’t have trouble procuring lethal medications by other means. A better question is how to provide resources for veterinarians so they never get to the point of contemplating death by suicide.

Changing culture

To that end, several organizations are implementing initiatives to support veterinarians, offering resources from education to meditation.

In addition to providing emergency financial assistance grants and links to crisis counseling, Not One More Vet is focused on shifting the landscape of the profession into one where veterinarians have better, broader tools to manage the demands of their careers. Says Jurney, “We can’t really get rid of moral stress, but we can prepare ourselves to deal with it better.” The organization also operates a popular private Facebook group for veterinarians where members can discuss challenges.

Jurney says that in addition to the kind of resilience and wellness training offered by Not One More Vet, veterinarians can help themselves by learning their “personal wellness barriers,” or the indicators that things have gone out of balance. For Jurney, a red flag is not sleeping well, but for a friend it might be that she’s sleeping too much.

“Your gut feeling is probably the most accurate measure you can have,” she says, but she encourages veterinarians to watch for mood swings and thinking or saying things like, “I can’t do this anymore” or “The world would be better without me.”

Wasson says boundaries are a critical issue.

“I’ve never come across a profession that was so boundary-less until I came into veterinary medicine,” she says. “Many vets provide care at the expense of their personal lives and their personal well-being without realizing that in the long term, it comes at the expense of patient care.”

Scheduling shorter work shifts could help reduce stress in the veterinary profession.

One way to draw boundaries, Wasson says, is for veterinarians to make sure they have a balanced schedule and a rich life outside of their shelter or practice. “If you’re working past the point of what’s sensible, responsible or sustainable to feel needed by your clients, you need to develop other relationships in your life,” says Wasson, who emphasizes that it’s critical that veterinarians have fulfilling relationships outside their workplace. “We can’t rely on work to give us everything we need, nor should we.”

For his part, Kipperman joined a team of other veterinarians concerned about gaps in training that contribute to moral stress for vets. The result is MightyVet, which offers free online training in resilience and coping, communication, financial management and other areas. The organization also offers the Mighty Mentor program, which matches veterinarians with seasoned professionals for peer-to-peer support. MightyVet’s future plans include working with schools to include these topics in basic veterinary education.

It will likely take some time for professional training and culture to change, but for veterinarians ready to enhance their coping skills, there are groups ready to help. Two things are clear: First, veterinary medicine is unlikely to become less stressful, but the impact of much of that stress can be mediated with the appropriate tools. And second, as colleagues and clients, those of us in the animal welfare field must remember that veterinarians are trying their best for animals every day, just as we are.