Yes, in our backyard

Turning the NIMBY attitude on its head, some shelters care for feral cat colonies onsite

A decade ago, Lisa Tudor, executive director of IndyFeral, never imagined that she’d one day be working with Indianapolis Animal Care & Control to help save the feral cats who live around the municipal shelter.

Her nonprofit group “had been doing TNR in the city, and we knew that there had been cats on the [shelter’s] property forever,” says Tudor. “We had tried before [to get permission to TNR the cats], but it never went anywhere.”

It wasn’t until spring 2010, when Teri Kendrick, a huge TNR advocate, became the shelter’s new chief, that things changed. Tudor recalls Kendrick saying, “We’re doing [TNR] in the city. Why aren’t we doing it here [at the shelter] to set an example for the city?”

That summer, IndyFeral did two mass trappings at the shelter. All 33 cats were spayed or neutered, rabies-vaccinated, ear-tipped, and given any needed medical treatment. Fifteen cats were friendly enough for adoption, four were euthanized due to extreme illness or injury, and the remaining cats were released back onto the property. Shelter staff regularly provides water and food and monitors the cats, while IndyFeral provides the labor-intensive trapping and any needed medical care, which relieves the understaffed shelter.

Some shelter staff were opposed to putting cats back outside, but their perspective changed when they saw how well the cats did and realized that friendly cats would be pulled for adoption. Their perspective on TNR changed, too, when they saw the electric water bowls and insulated shelters that IndyFeral provided for the feral cats. “It’s been a great learning experience for many shelter staff who didn’t understand or believe in TNR,” Tudor says.Nowadays, the shelter automatically calls IndyFeral if ear-tipped cats come in and, with information about a major intersection or address where the cat was trapped, IndyFeral can search its colony database and return the cats to their colonies. Feral cats without ear tips are still put on the euthanasia list, but IndyFeral is given the opportunity to contact the person who trapped the cat. “Many of these people are folks who have been bringing in cats for three, four years, and they’re actually distressed when they find out that those cats were euthanized, because nobody told them that,” says Tudor. “How do you expect the public to ever change their behavior if you don’t give them accurate information?”

Tudor realizes that even if staff wants to talk to people about TNR, they can’t do it in the five minutes they often get to speak with visitors. But IndyFeral has the time to explain how the program works—and once people understand, most opt for TNR over programs to trap and remove. Last year, IndyFeral removed 670 feral cats from the shelter, and Tudor says the number of impounds is slowly going down in the city.

The number of kittens running around the shelter property has decreased thanks to TNR, says Amber Myers, chief of Indianapolis Animal Care & Control. “Every municipal shelter probably experiences the same problem with animals being dumped and abandoned,” Myers says, “so when you have a program such as TNR, not only are you going to have an increased live release rate, you’ll also ensure that cats on your property are being trapped in a humane manner, spayed and neutered, rabies-vaccinated and managed.”

She’s proud that the shelter is leading by example in managing the feral cat colony on its property, and encourages municipal shelters to help improve their municipal ordinances so that managed feral cat colonies are allowed.

Déjà Vu All Over Again

Having IndyFeral as a partner has been hugely helpful in Indianapolis, but some shelters, such as the New Rochelle Humane Society in New York, are setting up camp for feral cats without an external partner.

When a pair of cats showed up at the shelter 15 years ago, staff fed them for about a year before trapping them. “We didn’t realize we could take it to the next step,” says shelter manager Dana Rocco. “It’s second nature to us now, but at the time, our first instinct was ‘How are we going to feed them and get shelter for them?’”

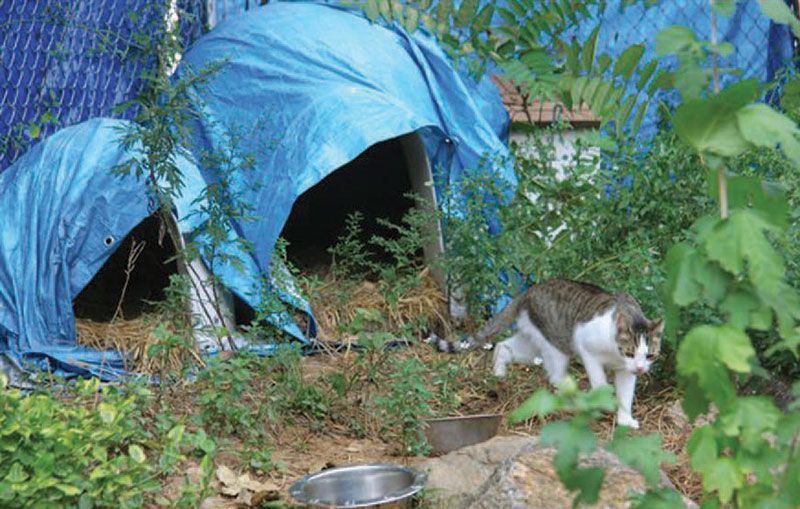

Over time, that’s changed. When another pair of cats showed up two years ago, staff didn’t wait. Now the shelter has straw-filled houses for feral cats at the front of its property and in the wooded back area. “Sometimes we see cats that we’re not familiar with, and quite often we’ll see [our cats] chase them off,” says Rocco.

“Everybody really enjoys them, especially the last two that we’ve seen become friendly after being so elusive,” Rocco says. With some coaxing by staff, the last two cats reluctantly came inside during the worst parts of winter, but neither was happy. Come spring, they were outdoors again.Managing the colony at the shelter has worked out well. When people come to the shelter asking about TNR, staff can explain the basics and even take them outside to see real examples of houses. “I mean, who better than us [to have a colony]?” Rocco says. “It’s a perfect opportunity to be a model for what you’re asking your community to do.”

Ten years ago, the shelter couldn’t interest people in TNR. Now it’s easy to get people to understand the purpose and importance of the program and how it benefits the cats and community. “I think that’s one of the huge benefits that needs to be promoted with TNR—that you’re vaccinating cats against rabies and creating a barrier” between people and wildlife against the spread of disease, says Rocco. The City of New Rochelle gave the shelter a $5,000 grant a couple of years ago. “I think they see the importance,” Rocco says. “I wish I could see it more with other towns and villages assisting either shelters or rescue groups.”

Meeting Their Communities’ Needs

If you think it gets cold in Indianapolis and New Rochelle, you haven’t been to central Alaska, where the temperature can go from a “warm” 20 degrees to a bone-chilling minus 40. In addition to the severe weather, there are many predators to limit a feral cat’s survival and keep the cat population from multiplying.

Loving Companions Animal Rescue, a volunteer-run animal shelter in North Pole, Alaska, started its colony with 30 cats it took from local animal control, the only such government-run facility in the region of the state known as the Interior. “In some of those areas, there are no roads,” says Donna Buck-Davis, the group’s director. But she’s able to take cats from those areas, thanks in large part to a local airline, Era Alaska, willing to fly rescue animals for free to save their lives.

Davis knows that life is hard on cats in the area, but she wants to give them a chance. The animals her group helps range from those who prefer not to be handled or aren’t friendly to those who don’t look so good—many have lost their ears due to frostbite suffered before rescue. “People know us and that we do not kill cats, so if they have a stray living in their area, they bring the cat to us,” says Davis. “We kind of adjusted to the needs of the community.”

Once cats go through their quarantine period, they’re free to come and go as they please. They have access to the warmth inside the building and can go outside, which is totally fenced to keep cats in and predators out. The adoptable and feral cats mingle. Many of the feral cats gain confidence and learn to trust people thanks to living with socialized cats. (Feral cats living in such harsh climates will need more oversight than other colonies; see Resources for information on constructing winterized cat shelters.)The cats may take a swat at each other once in a while, but staff and visitors haven’t had problems with the feral cats because they just run away. “We don’t corner them unless we’re trying to catch one, and then we’re prepared,” Davis says. “Otherwise all they want to do is live out a normal life—sun themselves in the summer, and play outside on the equipment that the Eagle Scouts built.”

Here Kitty, Kitty

In the warmer climate of Collierville, Tenn., Nina Wingfield, director of the Collierville Animal Shelter has lately been able to do something new: For the past three springs, her shelter has been able to take in cats and kittens from neighboring areas. That wasn’t the case when the shelter had more felines that it could handle, and trapped cats who were deemed feral were euthanized.

The shelter began its volunteer-run TNR program in 2007 after Wingfield approached the city and was told that she could spay and neuter feral cats if they had a place to return to.

Her TNR program was running smoothly until Wingfield was faced with three “nuisance” cats who had no caregiver. The neighbors weren’t buying TNR and wanted the cats removed. Although she hadn’t planned on having a feral cat colony at the shelter, “We were having a rodent problem inside and out, so we decided to make these cats our resident rodent patrol,” says Wingfield.

Boots, Tiger, and Cinnamon now live on the shelter property and enjoy a good scratch on the head from staff. There are warm houses and raccoon-proof feeding stations by the back door of the shelter, which is their territory. They don’t mingle with other cats who have subsequently been released on the property.

Wingfield also hadn’t planned on having more than three cats on the property, but that changed in 2009 when she attended a meeting of the sheriff’s department, where she volunteers as a first responder. The woman who gave a presentation on domestic violence victims seemed interested when Wingfield mentioned the shelter’s Safe Haven program for pets and asked if she could call Wingfield.

She did call, but not about the Safe Haven program. She told Wingfield that she’d been caring for feral cats and needed to move them because the building they lived in was going to be demolished. She told Wingfield she would make a donation to the shelter, and Wingfield agreed to help, because she knew the woman did a lot of feral cat trapping. “Well, I didn’t know the donation was $10,000,” Wingfield says.With that donation, Wingfield was able to build a feral cat habitat, and seven more cats came to live on the shelter’s grounds. Twenty-three cats now live on and around the rural property. Many of the cats came from neighborhoods that didn’t want them.

“These animals will never come into our shelter, unless they’re injured or we have to redo their three-year rabies,” Wingfield says. She adds that most of the cats can now be handled, so revaccinating them isn’t a problem.

Staff feeds the cats and checks on them, but the shelter refers calls about feral cats to its volunteer-run TNR program. When citizens bring feral cats they’ve trapped to the shelter, they’re always asked to take the cat back after the cat is spayed or neutered, and Wingfield says they comply nine times out of 10. The cats who aren’t wanted are worked into the shelter’s colony.

“I think it’s a wonderful example of the care that we’re giving to all homeless animals,” Wingfield says, “not just the adoptable."