Ask the Expert: Alley Cat Advocates co-founder Karen Little

Lessons learned from 24 years in TNR and community cat advocacy

Karen Little remembers a time when she and her husband, Hoyt, were “normal people” who were focused mainly on their careers, he as a banker and she as a music librarian. But then they moved from Virginia to Kentucky, where Little had accepted a faculty position at the University of Louisville, and it was during her walks to and from work that she began to cross paths with community cats.

Like many laypeople, she initially assumed that the solution was for her to pick up the cats and find them homes. Some went to friends and family members; others came into the Littles’ home and stayed. “We got up to what seemed, at that point, an abnormal number of five cats,” she says. “Not knowing that that was really just a few.”

In search of a more sustainable strategy, the couple started attending animal welfare conferences around the country. “We learned about two things that were lacking in Louisville,” she says. “One was a high-volume spay/neuter clinic, and one was trap-neuter-return.”

In 1999, they co-founded Alley Cat Advocates with an ambitious goal: to make Louisville the safest place to be a community cat. But they knew change wouldn’t be easy or quick.

At the time, Louisville had a large population of unsterilized community cats, and affordable spay/neuter resources were scarce. Nearly every cat who entered the municipal shelter was euthanized, and the shelter’s leadership, like much of the animal welfare field in the 1990s, didn’t support TNR.

Focused on their long-term vision, the Littles persevered. Alley Cat Advocates has since sterilized more than 60,000 cats, successfully lobbied for a city ordinance that endorses TNR, and evolved from an all-volunteer group with no brick-and-mortar facility to a staff of 12 working in a 4,500-square-foot “community cat complex,” which is located on the grounds of the municipal shelter and includes a spay/neuter clinic, administrative offices and space (including catios) for holding community cats with special medical needs.

Little, who retired from her university job eight years ago, serves as the organization’s full-time executive director. In this edited interview, she shares the lessons learned over 24 years in community cat advocacy and advice for TNR groups that want to grow their impact.

You put a lot of forethought into creating Alley Cat Advocates; can you describe that process?

We founded the group in February 1999 and didn’t do our first surgery until October 2000. That’s how long it took to get things like our logo, a template for our newsletter, all the protocols and infrastructure in place. We recruited our volunteers, formed our committees, chose our team leaders, and figured out how we would document our work and keep statistics. I knew once we got started there wouldn’t be any time for that stuff.

You don’t want to run an organization by the seat of your pants. It’s a business, and there have to be components of a business, such as volunteer management, fundraising and strategic planning. I can’t stress enough to anybody that if you don’t act like a business and have that infrastructure in place, you can’t make a difference big enough to make a difference.

How has your spay/neuter model evolved over the years?

At our first tiny clinic in October 2000, we did 12 surgeries in a private vet clinic. It showed me that just piddling around with one vet here and one vet there wasn’t going to do the volume we needed. I went out to San Diego and watched the Feral Cat Coalition clinic in operation and said, “Well, that’s what we need to do.”

From 2001 through 2016, we used a friend’s janitorial warehouse as our clinic space. We held 12 to 13 clinics a year with eight to 10 volunteer veterinarians and around 60 lay volunteers, and we would alter between 100 and 195 cats at each clinic. It was a very strong PR opportunity because everybody who came to that experience was energized by it. I think I was the only one who didn’t love it because it was an enormous amount of work.

In the meantime, the Kentucky Humane Society had launched a high-volume spay/neuter clinic. In 2016, when I just had had enough of the very work-intensive MASH-clinic weekends, the humane society’s leadership agreed to do as many surgeries as we would be doing with the two clinics combined. For the next five years, we outsourced our surgeries to them until we opened our own spay/neuter clinic.

In 1999, Karen and Hoyt Little co-founded Alley Cat Advocates with an ambitious goal: to make Louisville the safest place to be a community cat.

How did that come about?

Doing our own surgeries at our own clinic was always a long-term goal of mine. In 2018, the municipal shelter was planning a new facility, and there was one building on the campus that was going to go unused. The director at the time asked if we’d like to renovate and lease the building from the city for a nominal amount. We launched a capital campaign to pay for the renovations, and the clinic opened in February 2020. We currently do surgeries three days a week, about 50-60 cats a day. This enables the humane society clinic to put more resources into sterilizing large dogs, which remain an overpopulation challenge in our area. So our clinic can pull out six cat spays and give them time to spay a pit bull-type dog.

What are the benefits of having a dedicated space?

Starting around 2008, long before we opened our community cat complex, we rented a 1,000-square-foot room as our administrative headquarters with desks, phones and filing cabinets. This is where we responded to calls from the public, loaned out traps, trained trappers and held monthly volunteer meetings. It was a place that volunteers and staff could call a workspace, issues could be talked about and we could bond as people. If you can get space donated or find the money, I think having a central location is essential for the maturing of a group and improves the professionalism.

“You don’t want to run an organization by the seat of your pants. It’s a business, and there have to be components of a business, such as volunteer management, fundraising and strategic planning.”

—Karen Little

How has your relationship with the municipal shelter changed over the years?

Early on, I recognized that to be successful long-term, we’d have to partner with the municipal shelter. I started to build relationships with city council members, shelter staff and others who wanted a better solution for cats. In June 2012, the shelter launched an extremely successful return-to-field program. They haven’t needed to euthanize cats for time or space for six years now.

They’re ultra-supportive of us. Under our contract with the city of Louisville, they give us $40,000 a year to handle all TNR in the city, so all the calls that come into Metro Animal Services on community cats are fielded to us. We’re not the crazy cat ladies. We have a business plan; we’re respectful. We have a volunteer handbook and an employee handbook. We’ve had the Center for Nonprofit Excellence come in to talk to our board every year. We have a strategic planner come in every three years to provide an outside view and make sure we’re on the right track. That professionalism allows the government to feel safe working with us.

Can you talk about the importance of enlisting community members in TNR work?

I recognized early on that we as an organization weren’t going to be able to trap all the cats ourselves and that we needed to trust that the people who were calling us, who were invested in these cats and had given them names and loved them dearly, could be trusted to trap them. We give them the tools and training, and we counsel them if they’re having any problems. By using that model, it freed up our time to field the calls, bring in the money and focus on running the program, and it allowed those people to feel fantastic about the changes they made for the cats.

For cats in our county, the spay/neuter and other medical care is free, and that propels many people to do the legwork. We hold cats the nights before and after surgery, so caretakers don’t have to figure out where to hold a bunch of cats in traps in their own homes. We now have a part-time paid trapper who helps elderly, disabled and transportation-challenged caretakers. If a person doesn’t fall into one of those categories and for whatever reason doesn’t want to do the trapping, we offer them the option of paying $100, and we will send out a trapper for two visits.

What other changes have you seen over the decades?

When we first started doing TNR, the colony sizes we were helping were 20 to 40 cats. In Jefferson County now, the largest colonies we’re seeing are five cats. We’re getting a lot of the ones and twos. That’s a radical change.

They’re coming in healthier, too. And we get absolutely no pushback on TNR now. Certainly, there are still people who call and say, “I’m pissed about cats lying on my lawn chair.” We treat those people with as much empathy and support as the person down the street who wants the cats spayed and neutered.

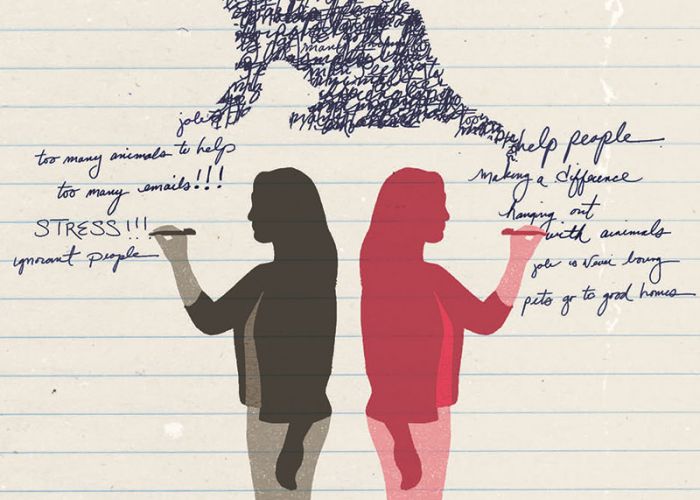

You’ve been doing this work for a long time. What advice do you have to prevent burnout?

You need to focus on, “Is it in your box?” We have calls every day asking us to find homes for kittens. That’s not in our box. You have to say that in your head over and over. “I’m tackling this problem; hopefully someone else in the world will tackle that problem, but it’s not mine.”

The box needs to be small enough to make it manageable. We’re not doing as good a job in surrounding counties as our county. If I focus on lack of success in those areas, I could be discouraged. But trying to do more than you can do is what causes burnout. There’s nothing wrong with doing well in one neighborhood. If you have the funding to do one target area a year, you’ve made a huge difference for those cats and those people, and then you look at doing more the next year.

For me, the vision is so clear and it’s so long term—that’s why I don’t burn out. I strongly believe there is no greater purpose in life than making a difference in the world, and this is what I landed on. I’m very lucky that my passion is my work.