Ask the expert: Ringworm screening and diagnosis

To win the spore wars, you need to be armed with the right information

Ringworm comes with its fair share of paradoxes. First, there’s the confusing name: ringworm isn’t a worm, but a skin infection caused by a fungus.

So on the one hand, ringworm isn’t a big deal. But since the type of ringworm that causes the most problems for shelters and rescues—Microsporum canis—is highly contagious to people and animals, it can certainly feel like a big deal when it spreads through your shelter. While the fungus itself won’t kill anyone, some shelters still euthanize infected animals because they lack the space (or foster care capacity) to house them apart from their regular population for weeks at a time.

Here’s another ringworm paradox: For a relatively simple skin infection (similar to athlete’s foot in humans), there are a lot of nuances to diagnosing and treating the disease. For starters, there are actually three types of ringworm you’re likely to encounter in sheltering and rescue, and they don’t call for the same treatment approach. And since there’s currently no “gold-standard” test for ringworm, you need to understand what the various diagnostic tools can and can’t tell you.

Fortunately, our knowledge of ringworm has progressed hugely over the past decade (thanks in large part to the pioneering work of veterinarians Karen Moriello and Sandra Newbury), but there are still plenty of myths and misinformation surrounding this disease, says Dr. Erica Schumacher, outreach veterinarian with the Shelter Medicine Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine.

In this edited interview, Schumacher shares her top tips for identifying and diagnosing ringworm; check back next Monday (or sign up for HumanePro News) to read her top treatment tips!

What’s your top ringworm tip for shelters?

Ensuring you have an accurate diagnosis is No. 1. That means first making sure it actually is ringworm and then identifying the type.

A lot of shelters are doing fungal cultures in-house, which we recommend doing if you have the capacity, but the problem is they may not know how to interpret the culture results. The dermatophyte test media on the culture plate has an indicator that will turn the gel red if ringworm is growing, but it will also turn red if some contaminants are growing that aren’t ringworm. So one of the biggest mistakes we see is assuming that if the plate turns red, it’s ringworm.

You need to learn how to interpret the culture plate. Colony growth on the plate will look a certain way. Ringworm is never deeply pigmented, so if you are looking at the plates every day and you suddenly get something that’s green or brown, even if the media turned red, it’s not ringworm—it’s a contaminant.

Why do you need to identify the type of ringworm?

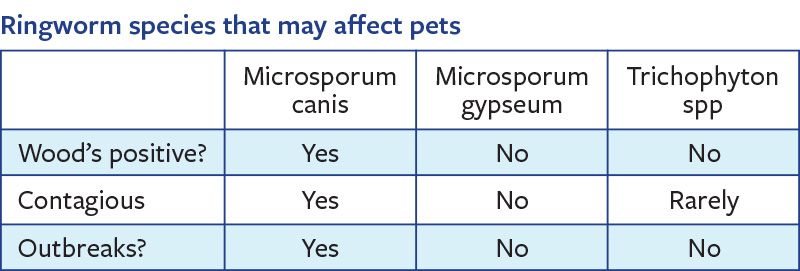

There are three main types of ringworm we encounter in small animal medicine, and we really need to know what we’re dealing with. M. canis is the one we should worry about, and it’s the most common type found in cats. Then there’s M. gypseum and Trichophyton, which look very similar but aren’t as concerning. They can cause lesions, hair loss and scabbing, but they aren’t as contagious, aren’t going to cause outbreaks in the shelter, and aren’t easily transferred to people or other animals.

We see shelters that think they have ringworm and just treat it the same regardless of type. You might have a cat with an M. gypseum lesion who requires no isolation and very little in the way of treatment, but if shelters are just thinking “ringworm,” they’re doing the full lime sulfur baths twice a week, oral anti-fungal medicine, and isolation for six or more weeks. It’s a very expensive process, and it’s also really hard on the animal.

How can you tell what type of ringworm you’re dealing with?

M. gypseum and Trichophyton don’t glow under a Wood’s lamp, so that can be a helpful tool to see what you’ve got, though I would still recommend doing a culture and looking at that colony growth under a microscope. So we’ll use a piece of transparent Scotch tape and some special stain and look at it under the microscope to see if we can ID the type.

What about ringworm in dogs?

Everyone panics about ringworm in dogs. M. canis can happen in dogs, but ringworm in dogs is most often M. gypseum. M. gypseum lives in the soil, so we’ll often see it on dogs’ paws or ears because they’re digging in the dirt.

So you absolutely have to ID the species. We’re talking about shelters holding litters of puppies in isolation for formative weeks of their lives, but if it’s M. gypseum, they don’t need this massive treatment, they don’t need isolation, they can move on their way. I would often do lime sulfur just on that lesion and send the dog home with adopters and that was it. No restrictions in the shelter. Theoretically, immunosuppressed animals or people could be susceptible to M. gypseum or Trichophyton, but I’ve never seen a case of that spreading to other animals or people.

Can you talk about the importance of screening animals for ringworm?

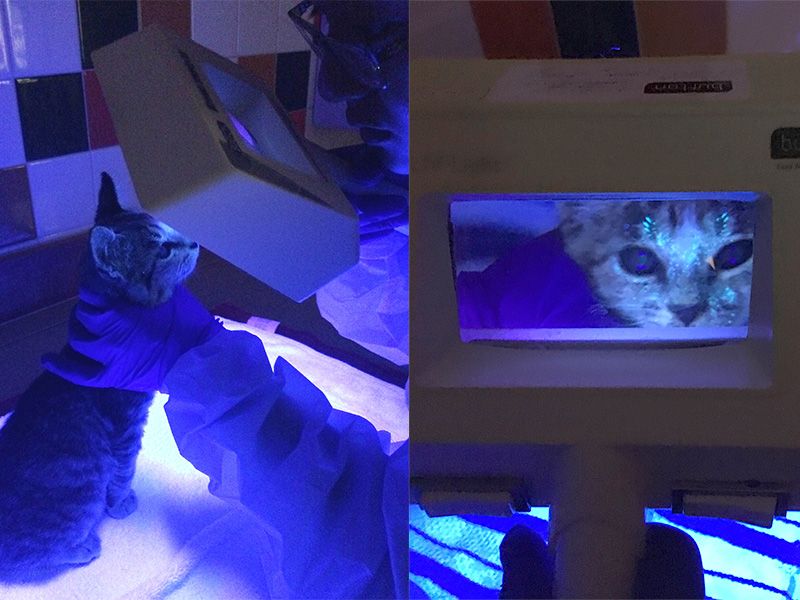

Catching ringworm on intake is going to be your best way to prevent outbreaks. We recommend a careful intake exam, especially for cats, looking for lesions and hair loss. We recommend that every shelter do a Wood’s lamp exam on their cats on intake. This will identify the majority of infected animals, but the incubation period is two to four weeks, so you need to train your staff to look daily for signs like hair loss, and make sure that if they notice something, they’re empowered to bring it up.

Catching ringworm on intake is going to be your best way to prevent outbreaks. We recommend a careful intake exam, especially for cats, looking for lesions and hair loss. We recommend that every shelter do a Wood’s lamp exam on their cats on intake.

—Dr. Erica Schumacher, University of Wisconsin-Madison Shelter Medicine Program

How accurate is the Wood’s lamp?

Back in the day, we were taught that the Wood’s lamp would only pick up 50% of M. canis ringworm cases, so most people thought, “Well, why bother?” The reason that all came to be is because of what we call your “dust mop” cats—the ones who pick up ringworm spores on their coats but aren’t truly infected.

The reason ringworm-infected hair will glow is that the ringworm lives in the hair follicle and produces a metabolite that will coat the hair as it grows out. The metabolite is what glows, so if you have any glowing hair, that’s an infection; the ringworm is in the follicle. Animals can pick up spores on their coat but not be infected and they won’t glow. I’ve never seen a clinically significant case of ringworm that didn’t glow under a Wood’s lamp.

When you’re interpreting your Wood’s lamp, you want to look at the hair and see if it glows all the way down to the base of the hair. If you see some things that are glowing but just at the tops, that’s typically medication, or it may be resolving ringworm where the hair is growing out and the glow remains at the tip of the hair. You can differentiate between these by attempting to wipe off the glow with a damp cloth; glow from ringworm cannot be wiped off. Also, sebum wax can glow; scabs and crusts will glow. That’s where I’ve seen some people thinking they have ringworm-positive dogs because the crust is glowing, but it’s not the crust that needs to glow—it’s the hair.

You want to use a corded Wood’s lamp model with a specific wavelength of 360-365 nanometers. The battery-operated handheld or blacklight flashlight models may pick up some infected hairs but won’t give you the power you need, and you can easily miss more subtle lesions.

What are the benefits of doing fungal cultures in-house?

The most important reason is to get that quantitative result. Labs typically don’t give you quantitative results; they just say positive or negative. That means your dust mop cat will be positive for ringworm, but you have no idea if they’re infected or just have a spore or two on their coat.

In a culture, if you’re a dust mop, you’re only going to have a few colonies growing on your plate. If you’re actually infected, you’ll have a lot of colonies growing. So having that quantitative result is the core reason for doing the culture, and it’s an extra bonus that you’ll get results faster and it’s cheaper.

What other diagnostic tools do you use?

The PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test is another option. There are times when it’s great and times when it’s not. PCR is a very, very sensitive test that can pick up a single spore on the entire cat. It won’t give you a quantitative result—it will just say positive or negative—so any of your dust mop cats will be positive. It doesn’t mean they’re infected or that they need treatment.

You don’t ever want to use PCR to monitor how well your treatment is doing. The animal could be completely cured and still be PCR-positive because the test is picking up dead ringworm on the coat. PCR can be helpful if you’re not sure what you’re seeing on the Wood’s lamp, or if your culture is growing and it looks like it’s ringworm but it’s not producing the macroconidia you need to identify the type.

There’s another test we use, the trichogram, which is the direct examination of the hair under a microscope. So if you have this Wood’s lamp-glowing hair, you can pluck that hair and look at it under a microscope. Normal hair will be thin and smooth; ringworm-infected hair will look swollen and the edges will be frayed, and you might see little spores.

That’s the closest thing we have to a SNAP test for ringworm. Because you can do your Wood’s lamp exam at intake and then look at that hair under the microscope. If you’re choosing a hair that glowed under the Wood’s lamp and looks like ringworm under the microscope, you can be pretty certain it’s M. canis. With that kind of information, we’d start treatment. You take a culture before you start treatment, but you don’t wait to start treatment. The culture is just to confirm.

What do you tell shelters that are experiencing an outbreak?

Don’t panic. We can get through this. We know what we’re dealing with, we know how to handle it, we just have to go through the steps. It’s a curable disease. There are even shelters adopting out cats and kittens with ringworm, sending them with their treatment, and people will do it.

The first step for tackling a true outbreak of M. canis is to identify all the infected cats. That means a thorough Wood’s lamp exam on every cat in the shelter and often times culture everybody at the same time, depending on how big of a problem it is and how certain we are that the shelter does have a problem, because a lot of times people think they have ringworm and it’s not. So identifying all the infected cats, getting them into treatment, and then identifying all the exposed animals and having them in a separate area for very careful screening.

And we look to see how this happened in the first place, how it got in and how it went unnoticed. Usually we need to implement screening on intake, we need to implement daily monitoring, and after that, once people know what to look for and do about it, they’ll be in a much better place.