Choosing the difficult

Conceptualizing the challenges of your work in a new way can lead to empowerment

Whether you’re intimately acquainted with the term “compassion fatigue,” or hearing it for the first time, if you’re in animal welfare, it’s a subject that merits attention. Compassion fatigue is a real and normal phenomenon experienced by many working in the caretaking fields. In Compassion Fatigue in the Animal-Care Community, Charles Figley and Robert Roop write, “By understanding … compassion fatigue as the natural, predictable, treatable and preventable consequences of [caregiving] we can keep caring professionals at work and satisfied with it.”

If you are feeling the pain of compassion fatigue, there is nothing wrong with you. In fact, it indicates that you are a caring and empathetic individual. It’s important, though, to take steps to ensure that it doesn’t become a permanent state.

Compassion fatigue is also known as secondary stress disorder, vicarious traumatization, empathic strain, and secondary trauma. But no matter what you call it, compassion fatigue can affect everyone working in the field of animal protection; don’t imagine for a minute that this doesn’t apply to you if your job doesn’t include direct animal contact.

In coming issues of Animal Sheltering, we are going to explore the phenomenon of compassion fatigue—what it is, how you can take care of yourself, and how you can support others around you. In this first article we’ll start by understanding some common terminology, do an exercise to illuminate the relationship between what we love about our work and what we find most challenging, and finally examine (and ideally affirm) our choice to be doing that work.

Defining the Issues

In the simplest terms, compassion fatigue is what many caretakers experience when they are repeatedly exposed to the trauma of others. Laura van Dernoot Lipsky describes it beautifully in her book Trauma Stewardship (a must read), writing that trauma stewardship “refers to the entire conversation about how we come to do the work, how we are affected by it, and how we make sense of and learn from our experiences.”

This powerful way of thinking puts you in the driver’s seat. Instead of perceiving yourself as a victim of the work you do and the challenges it entails, it invites you to acknowledge that you chose to be here, and you choose to stay. It also provides you with the opportunity to actually influence how you allow the work to affect you. So often, we perceive ourselves as being influenced by the negative external factors around us. What if you asked yourself, “What can I do to influence my own thinking? What can I bring to mind that will positively influence how I am relating to the work I do?”

In the conversation about compassion fatigue, two important concepts are primary trauma and secondary trauma. Primary trauma is direct, personal trauma, which most of us have experienced in one way or another (e.g., a traumatic accident, some type of abuse, performing euthanasia, a traumatic loss). Secondary trauma can happen when we are repeatedly exposed to the trauma of others.

Primary trauma and secondary trauma are intimately linked; one of the most important things you can do to stay healthy in the face of secondary trauma is resolve your primary trauma. If you haven’t resolved your primary trauma or coped with it effectively, exposure to secondary trauma is much more challenging.

This is especially true if your primary trauma is similar in nature to the secondary trauma that you’ve chosen to be near by working in this field. For example, say your dog got lost when you were a child. You searched shelter after shelter and never found her. It might be that much harder for you to work with lost dogs, because your own loss is touched with each new case. While it may be a difficult task, resolving your primary trauma will help you safeguard your long-term well-being. If this seems relevant to your experience, seeking the help of a mental health professional is a great way to start that process.

At the core of self-care is the notion that we are responsible for our own choices and our own experiences. If we want to remain in the field of animal protection for the long haul, we must care for our own well-being while we care for others. The bottom line is that nobody is forcing you to be in this field, and it is possible to experience joy even in the face of sadness and challenges. Nobody is responsible for your career other than you—and this is good news!

Getting It Down on Paper

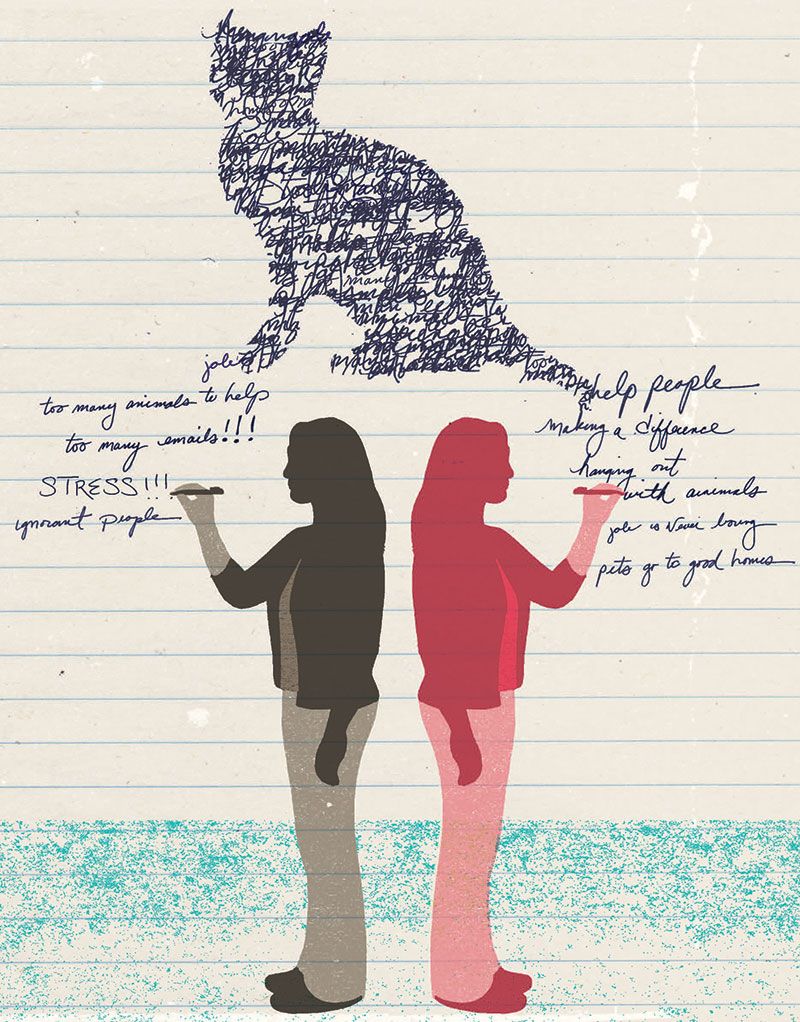

Try this: Find a quiet place, and give yourself about 15 minutes for this exercise. You’ll need a pen and two pieces of blank paper. On the first sheet, make a list of all the things you enjoy, cherish, and appreciate about the work you do. On the other sheet, make a list of all the things that are really difficult, challenging, and upsetting about your job. Make both lists as exhaustive as possible, and don’t worry about finding the right words—just brainstorm, take your time, and get it all out.

When you’re done, take a moment to study your lists. It’s likely there are amazing things on the first list, while ugly things populate the second. But what I want you to notice is this: There are things on your list of positives that only exist because of the corresponding problem or dilemma on your list of challenges. For example, witnessing suffering is clearly difficult, but relieving the suffering of animals is so often on the list of things that are deeply satisfying. “Ignorant people” are often on lists of difficulties, but the ability to educate and change peoples’ minds is often on lists of job satisfactions.

These two lists are actually just one thing: the entire character of the work you’ve chosen. It’s possible that you took your job for the things on the good list without thinking much about what would be on the hard one. But you also probably knew that you were getting involved to make a difference—and you probably knew, deep down, that it wouldn’t be easy.

That desire to make a difference is about taking on that challenging list. Inviting that list into your life was implicit in your acceptance of your work. Understanding that this is your choice is a powerful thing. If your relationship with that difficult list is believing that it’s something you didn’t actually choose to bring into your life and you are, at best, tolerating it, you’re going to have a very different (and much more difficult) relationship with the day-to-day challenges of your work.

Don’t misunderstand. This does not mean that you should just lie back and stop trying to improve things. It does mean that you can relate to that difficult list more powerfully. What if your attitude, when it comes to working with people who have offensive ideas about how to treat animals, was “Sign me up!”—because you’re committed to creating a humane world? You put yourself in this field for a reason: Because you know that you can make a difference. You wouldn’t remain where you are if you didn’t choose the opportunity to be in the presence of ignorance. That is where the difference gets made, right?

Think about this: You could go work anywhere in the world and you’d have a completely different set of positives and negatives on each list. Think about what your lists would look like if you worked as a pediatrician or high school geometry teacher. Your life would be filled with completely different successes and complaints. Think about the problems with which you’re willing to grapple. What are the challenges you most want to take on, because those lead you to the successes most worth having? If your work in animal protection does not provide you with the challenges you feel are most worth tackling, you should consider moving on to grapple with something else. Put yourself where your heart is. It’s that simple.

Every day you wake up and go to work, you are making a powerful statement that this is work you think is worth doing, and the challenges you face every day are the ones that you are willing to face. Think about your list of difficult things, and see if you can own it as if it’s what you want in your life. If you find deep satisfaction in educating people about animals, then you might spend your time hoping that uneducated people show up in front of you. This is your opportunity to make a difference. This stance is not always easy, but it’s always worth the effort.

In the next issue of Animal Sheltering, we’ll explore how our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems influence our minds and bodies, as well as how our minds and bodies can influence those systems for the best. Stay tuned!