Community outreach creates community advocates

In East Baton Rouge, Pets for Life clients successfully tackle a barrier to affordable, accessible veterinary care

Before last year, most members of the East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, metro council had never heard the term “pet resource desert.”

Jillian Sergio, executive director of the Baton Rouge-based animal shelter Companion Animal Alliance, was eager to show them.

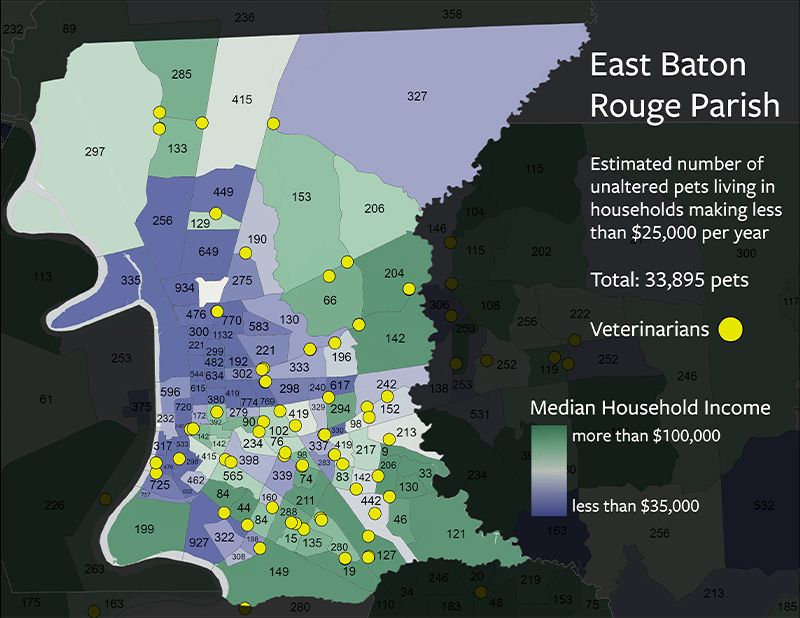

In spring 2023, she came to the city hall armed with a map of the parish displaying the number of unaltered pets in households with annual incomes less than $25,000. On another map, color-coded dots showed pet supply stores, grocery stores and veterinary clinics clustered in the more affluent areas of the parish—and largely absent from lower socioeconomic areas.

Sergio explained that most residents in the underserved neighborhoods rely on public transportation. She asked council members to imagine someone without a car trying to get a sick or injured pet to a veterinary clinic several miles away.

“We’re in Louisiana,” she says. “In the summer, you’re not walking your pet anywhere longer than two minutes away, and there’s no pet-friendly public transportation.”

By helping council members understand the challenges too many pet owners in the parish experience, Sergio hoped to persuade them to remove a barrier her organization faced in serving them. About a dozen years earlier, some local veterinarians, fearing that the nonprofit would compete for business, had successfully lobbied for an ordinance to prohibit the organization from providing medical services to owned pets.

The facts Sergio presented at council meetings were compelling, but what resonated most with elected officials were the words of residents who’d experienced the lack of affordable, accessible care for their pets firsthand. They called and wrote council members and visited their offices. They attended a public hearing on the ordinance, wearing blue T-shirts with CAA’s Pets for Life Baton Rouge slogan.

This outpouring of community support was crucial to the lobbying effort, Sergio says. It was also a tangible sign of how far her organization had come.

Building community trust

In its early years, after it took over the contract to operate East Baton Rouge’s only open-admission animal shelter in 2012, the Companion Animal Alliance had a poor reputation and little community support.

“We went through a lot of struggles like a lot of shelters do,” Sergio says. But “we started being very transparent about everything we’re doing” in the shelter, in addition to performing community outreach.

Rachel Thompson, senior program manager for the Humane Society of the United States’ Pets for Life program, remembers when CAA joined the Pets for Life mentorship program in 2017. “They already knew they wanted to do community support work, and they were really ready for it,” she says.

When CAA’s Pets for Life Baton Rouge program launched later that year, team members transported pets to the parish’s only low-cost private practice veterinary clinic for spay/neuter, vaccinations and other medical care. In this way, they worked within the limits of the local law that prohibited the organization from providing direct medical care to owned pets. But as their community outreach efforts expanded to more zip codes, Sergio and her team knew they needed more options.

Last year, the time felt ripe to challenge the veterinary care barrier. By then, Sergio says, CAA had proved it could serve East Baton Rouge’s underserved neighborhoods without affecting the bottom lines of local veterinary practices. Even more important, the organization had garnered the community support it would need for a successful campaign.

Much of that support Sergio credits to the shelter’s Pets for Life program and its philosophy of forming relationships and offering pet care services in a positive, nonjudgmental way.

Before Pets for Life, many residents in East Baton Rouge’s underserved neighborhoods had only had negative experiences with animal welfare professionals, she says. Today, CAA’s biggest volunteers are people who started as Pets for Life clients, receiving support with their own pet care needs. Now they sort supplies at the shelter’s pet food pantry, deliver pet food to people in need, foster shelter animals, and engage with their neighbors on issues such as spay/neuter and trap-neuter-return.

“They’ve embraced our entire organization,” says Sergio.

Harnessing compassion

Among the people lobbying the East Baton Rouge city council last spring was Jamal Hughes, a soft-spoken man who spends much of his free time delivering pet food to struggling families in the parish. Calling council members and attending meetings took a lot from the naturally shy Hughes, Sergio says, but his attitude was, “This is what you need; I’m on it.”

And there was Pamela Fance, a school bus driver who is known in her neighborhood as an animal lover and a woman who’s not afraid to speak her mind.

During Sergio’s initial meetings with council members, she often heard the same comment: “Oh yeah, we’ve heard from Miss Pamela,” they told her. Sergio’s response: “Well, you did, because she’s not letting this go. She’s gonna show up at your office. She’s gonna call you, and she’s gonna write a letter.”

These efforts paid off in mid-June when the East Baton Rouge metro council voted unanimously to remove the restriction that prevented CAA from providing direct veterinary care to owned pets.

“We as a program are always bringing to light barriers that communities face when accessing care. When we have a partner willing to advocate for people’s rights, it’s an extraordinary moment.”

—Rachel Thompson, Humane World for Animals

Soon after, Pets for Life Baton Rouge began holding vaccination clinics in its focus areas.

In the past, the team transported pets, one van-load at a time, to a private clinic and paid $25 to $50 per animal. Now, with donated vaccines from Petco Love and volunteers from Louisiana State University’s veterinary school, “we can vaccinate 200 pets for $200,” Sergio says.

Next year, CAA hopes to have a mobile veterinary clinic that it can take directly to the neighborhoods it serves. For the first time, their Pets for Life clients will be able to meet the veterinary staff providing their animals’ care.

Thompson, who accompanied the Pets for Life Baton Rouge team when they first knocked on doors in focus neighborhoods seven years ago, couldn’t be prouder of what the organization has achieved. “We as a program are always bringing to light barriers that communities face when accessing care,” she says. “When we have a partner willing to advocate for people’s rights, it’s an extraordinary moment.”

For Sergio, the metro council vote was a testament to the power of community outreach to harness the compassion of people who have historically been left out of the animal welfare movement. Ultimately, she says, it was the Pets for Life clients who got the revised ordinance passed.

“I don’t even like to refer to them as clients,” she adds. “We care about them. Our Pets for Life director knows their entire family history and their animals’ history. They’re friends.”