A delicate balance

On an island with limited resources but deep pride in its horses, Humane World partners with locals to forge a path forward

The injured foal has tried to find some respite from the harsh glare of midday, wandering into a stranger’s backyard to seek the shade of two palm trees there. Now she lies on her side, barely moving, just off the main street out of Esperanza, a pretty little town on the island of Vieques, Puerto Rico.

She is breathing, but not easily. Swarming flies gather on the deep tears in her flesh. Every now and then, she tries to brush them away with her tail.

Behind the yard, a few scattered houses and dense green foliage block a rocky drop-off above the blue waters of the Caribbean. Only a few hundred feet away, beach bars and boutique hotels overlook yachts moored in a placid harbor as their owners on shore sip piña coladas or haggle over the price of a sea kayak rental. Occasionally, a breeze lifts a strand of reggae music from one of the bars high enough to hear.

All that seems a million miles away as Kali Pereira of The HSUS tries to get close to the foal to assess how badly she’s hurt. Pereira has watchful company: Beyond the yard, also intensely focused on the foal, are two grown horses—a stallion and a mare—watching the smaller horse and the human activity that now surrounds her. They know something is wrong with their baby, and they’re not at all sure about the intentions of the woman showing her so much attention.

A few days ago, the foal and her herd were roaming the streets of Esperanza, and that’s when she was attacked by a pair of loose dogs. The dogs bit her badly, tearing at her neck and sides before they were caught and pulled away. Dickie Vest, an equine veterinarian visiting the island as part of The HSUS’s work there, had heard about the attack and gone out to treat her wounds. He’d given her decent odds of surviving if she got the antibiotics he’d prescribed.

But, like most horses on Vieques, the foal and her parents haven’t stayed confined in a paddock, in a place that would allow veterinarians to come back to make sure she’s eating the apples where her medicine was hidden and that her body is responding. Instead, she’s spent the past few days limping through tiny yards, dense patches of jungle and narrow roads, getting weaker day by day. For several days, no human has been able to get close enough to see how she’s recovering.

Until now, when Pereira gets a close look at her wounds and sees: She’s not.

That Pereira is here at all is pure luck: Someone who knew what had happened to the foal and knew she needed follow-up care spotted her and called Pereira. And now Pereira paces outside the fence, murmuring some comfort to the foal, trying not to alarm her nervous parents nearby, making one desperate phone call after another.

She’s facing a difficult reality of working on this beautiful but under-resourced island. The foal will likely need major surgery to survive, but there’s no equine veterinarian on Vieques. She could call the police, who have the authority to act in situations like these, but the outcome there is almost a foregone conclusion—a quick death, likely by gunshot. The private companion animal veterinarian who splits her time between Vieques and the main island of Puerto Rico has equine expertise and could come out to assess the animal, but she wouldn’t be able to treat or euthanize the foal without the owner’s permission.

And because this is Vieques, it’s not at all clear who that owner is.

It takes Pereira and the rest of the HSUS team several more hours to figure out a way to confine the foal and her parents so that a veterinarian can safely examine her. It takes more time for José Cruz, a local preacher and horseman who’s working with The HSUS and who knows most people on the island, to call enough of his connections to figure out who the foal belongs to.

When the veterinarian finally comes out to assess the animal, within minutes, she’s able to tell what Pereira feared from the start: The little horse won’t survive. She’s too badly hurt. Even in a place with many more resources, at this point, a peaceful death would be the only humane option.

It’s a disheartening ending for everyone involved—especially for the owners, who hadn’t realized how badly the foal was hurt, and for Pereira, who has been the chief witness to the foal’s suffering and who spent hours trying to map a path to a better outcome.

It’s also a reminder of the reasons Pereira is in Vieques. She has been coming here for months now, using her animal handling and technical skills to help the island’s horses. Pereira is the senior deer program manager for The HSUS, and usually she’s handling research work on that species. But here on the island, “there’s a huge gray zone between owned and wild horses,” she says. The animals move around unconstrained, the way deer populations do stateside.

The foal is only one of thousands of free-roaming horses here. Her suffering was painful to witness, and similar scenarios are all too common on Vieques. But the partnership between the local community and The HSUS has the potential to change the game.

Vieques, some 20 miles long and 5 miles across, is a little island with a controversial history. From 1940, when the U.S. government appropriated a large amount of land here, until 2003, the U.S. Navy had a large presence on Vieques. It included a munitions depot on one end of the island and a bombing range on the other; for years, locals lived with naval planes and warships conducting war games and military exercises in their own backyard.

Resentment among Viequenses—who are American citizens—grew over time, and that anger came to a head in 1999, when an off-target bombing run killed a local security guard and injured several others. The incident triggered escalating protests that went on until the Navy finally abandoned the island in 2003, turning its land over to the Department of the Interior.

Since the Navy’s departure, more issues have come to light: Vieques is a poor island, with an annual per capita income of less than $9,000. Rates of cancer and cardiovascular diseases are higher on Vieques than elsewhere in Puerto Rico; many residents and scientists believe this is due to toxic chemicals left over from the years that the Navy was dropping bombs here. The EPA designated parts of the island as a Superfund site and spent millions of dollars on cleanup, but the environmental damage had a huge impact on local fishermen. There are still areas around the island where signs warn of unexploded ordnance; in 2013, a diver found a massive unexploded bomb embedded in the ocean floor off the island’s coast.

Despite this history, the island is an extraordinarily beautiful place, with pristine beaches, swaths of jungle filled with birdsong and the cries of the coquí—a native frog species named for the sound of its mating call—and a world-famous bioluminescent bay. In the time since the Navy left, tourism has become a much-needed source of revenue here, and the island’s horses are part of its appeal.

Horses originally came to the New World on the boats of the Spanish conquistadors, and the horses on Vieques are mostly of a breed called paso fino, a mix of several breeds from North Africa and Spain. “Paso fino” means “fine step,” and when you see the horses pick up speed, you understand where the name comes from: Their gait is beautifully smooth, looking like something that must have been taught. It’s not—while training can enhance the horses’ step, the fast, even clip is how they naturally move.

Visitors are charmed by the horses, who roam the towns and roadsides with their herds. To many tourists—accustomed to cultures in which horses are typically kept behind fences and boarded in stables—the way the horses move freely about the island suggests that they’re wild.

But it’s not that simple. The equestrian culture here has evolved in a different way. Most of the horses here roam free, but if you look closely at the animals, their manes full of sandspurs and their ears often full of ticks, you’ll often notice a mark on their hide, scarred over but visible. These are brands, denoting that someone on the island claims this horse. Even horses who don’t have a visible brand may have an owner.

It’s a small island, with lots of vegetation the horses can eat, so many locals don’t keep their horses on their property, instead allowing them to roam freely and fend for themselves. When people on the island need their horse, Cruz explains, they will simply go out and find the animal, use him for the work they need done, and then return him to his herd.

This is how it was during his childhood, and while the island has evolved a bit over the years, its way of managing the horses hasn’t changed much. He had a horse of his own when he was a boy. He left the island for many years, working on farms and horse facilities around the mainland U.S., and when he returned to Vieques after more than a decade, he found his mare again—still with the same herd, chomping the greenery in the same area she had always grazed. On Vieques, a family who owns a horse will claim ownership of her offspring, too, so it’s common for one human family to be connected to a line of horses for generations—the equine side of the clan, in a way. Cruz has children of his own now; like him, they started learning to round up the horses and ride them almost as soon as they could walk.

But because the horses here aren’t confined, they roam freely and breed unchecked. And their numbers have risen—the statistics are debated, but estimates range up to 3,000 animals, close to one horse for every three human residents on the island. Sources of fresh water are scant, so the horses often come into the two main towns looking for a drink. Sometimes they damage water pipes. They wander through the narrow streets, grazing in the yards, scavenging people’s trash for food, knocking down fencing to get at tasty fruits in the trees. They are, in some ways, like docile, rideable, 850-pound raccoons.

As the equine population has risen, so has tourism. As more visitors come to Vieques, providing revenue and jobs for an island that desperately needs them, automotive traffic has increased. With more horses in densely populated areas of the island, there are more traffic accidents, which are dangerous for the people involved and often cause grievous injury to the animals.

Vehicular and other serious injuries—like the dog attack on the little foal—often prove fatal. Given most residents’ limited financial resources and the low availability of veterinary care, many injuries that might be treatable elsewhere necessitate euthanasia, but with the difficulties in ascertaining ownership, even providing that small mercy is often no simple matter.

No one wants the horses to disappear. They’re a much-loved part of the island’s cultural identity and a source of pride for many Viequenses. But it’s increasingly clear that their numbers need to be controlled to reduce these tragic incidents and that the local community needs more resources to help the animals thrive.

That’s why Pereira and the rest of the team from The HSUS and Humane Society International (HSI) are here. They’ve come at the request of the island’s mayor, invited after word spread about their animal welfare efforts on the main island of Puerto Rico. The HSUS’s Tara Loller, who helped to spearhead the initiatives, says it’s the first time that the horses on this island have gotten large-scale help.

With the support of donors—some of whom visited Vieques in January to participate in the work—the HSUS/HSI team is partnering with the municipality to increase the health and welfare of all the island’s animals, with a particular focus on its horses. The project, which has provided educational resources, veterinary and grooming supplies, spay/neuter clinics for local animals and a wellness clinic for the community’s horses, has engaged a wide range of HSUS staff, requiring expertise in animal handling, cruelty investigations, wildlife management and biology, community outreach, humane education

and more.

At the center of it all is the equine population control project, which Pereira has been leading. With authorization from the municipality, Pereira and other trained staff are tracking the island’s free-roaming horses and dosing the mares with a vaccine called PZP, a variation of which has also been used on deer populations. The vaccine, which has been in use since the late 1980s, prevents conception for around a year. “It changes the locks on the eggs,” Pereira explains, refusing entry for sperm and allowing for targeted birth control. To ensure the delivery of booster shots and accurate tracking of the animals over time, the teams make extensive notes as they work, identifying the horses not only by their unique markings but by their location and the horses they tend to hang out with.

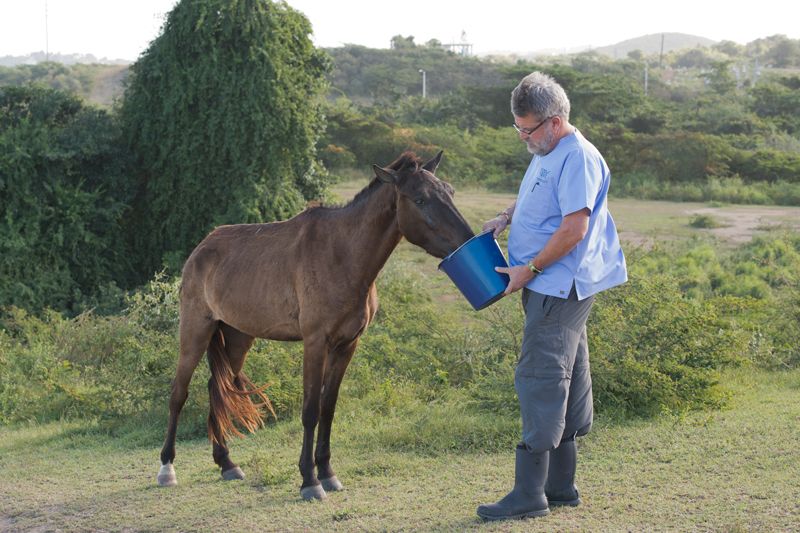

In the field, the darting process varies with the personalities of the horses being targeted. For the horses grazing an open swath of grassland near the tiny Vieques air strip, the lure is simple: When the darting team spots a mare in need of her booster grazing among the herd, Dave Pauli, senior adviser for wildlife response and policy, gets out of the Jeep and retrieves a bucket full of sweet feed.

When he starts shaking it, the feed rattles in the bucket, like a maraca full of deliciousness, and the horses in the valley raise their heads, flick their ears and start loping toward the humans as Pauli scatters a trail of feed along the grass. Their soft noses trace the dusty ground, nibbling up the pellets of feed, and Pereira is able to get into position with her dart gun.

Pereira aims and fires, and the dart flies perfectly into the broad muscle of the horse’s rear leg. The horse startles and jumps forward, glancing back peevishly at the dart hanging from her skin. She flicks her tail at the irritating little metal insect. After a few steps it comes loose, and she returns to noshing the trail of feed Pauli has laid down, wandering after the rest of the herd. Pereira collects the dart and makes her notes. One more mare is good to go.

“I am so excited about the opportunities these kids will have for their animals to be healthier. You can just see the pride these kids have in their horses, and now they’ll be able to talk about how well they take care of them. And who knows which kid here might turn out to be a future vet?”

—Barbara Long, HSUS supporter

It’s not always so easy—other horses are leerier of strangers, less tantalized by the lure of the food bucket. At various moments during darting, the team members have to circle around, using walkie-talkies to coordinate movements with each other so that one person can block a skittish horse’s escape route while another takes a shot. At one point, a little band of horses escapes off into the dense foliage near the beach, and the dart team tracks them into it, circling in behind to push them back into the open, the horses bursting out of the brush at full gallop.

At such moments, the darting takes on the feel of a hunt—only instead of bullets bearing death, the team shoots darts loaded with the possibility of a healthier life. The application of PZP will not only help reduce the population and diminish conflicts, but it will also provide relief for the mares: Having a foal every year—a reality in a free-roaming horse population—is a major physical drain on their bodies.

The darting work here will go on for several years. It has wider potential stateside, too: Right now, the Bureau of Land Management oversees territory occupied by thousands of wild horses roaming unconstrained across the American West; there are hundreds of thousands more animals on tribal lands. These horse populations are often the target of ranchers, who see them as food competition for their cattle herds, and so they’ve been the target of culls, roundups and slaughter.

“By learning how to apply PZP to horses within this closed island system, where the animals can all be identified and tracked over time, we can learn how it might work best in less controlled environments like the Western plains,” says Stephanie Boyles Griffin, senior director of innovative wildlife management and services for The HSUS. “Our hope is to scale it up later for other uses,” reducing the viability of arguments for lethal and cruel measures of population control.

The local government on Vieques has reached out to let the community know what the dart teams are doing and how the vaccine works. But miscommunications still happen. When outsiders come in to suggest changes to the way a community does things, it’s always a sensitive issue.

That’s made earning the community’s trust all the more important. As a local who grew up on the island, Cruz has been hugely helpful in bridging occasional communication gaps. That’s how he connected with The HSUS in the first place—Pauli was in a local feed store, trying to buy supplies using hand gestures and a smattering of Spanglish, and Cruz overheard and stepped in to translate.

Since then, he’s come on board and regularly accompanies the darting teams into the field. He’s superb at handling the horses, but even more, he’s able to connect with worried Viequenses who don’t know why these outsiders are shooting darts into their equine neighbors.

“Some people thought we would be taking the animals away, or thought that the drug would cause a pregnant mare to abort the baby,” Pauli says. “He has been critical in helping us let people know that we are here for no harm.”

By acting as a communicator and role model, Cruz is helping establish a new approach to equine care and ownership on the island. Pereira is working to get him certified to administer PZP. After the HSUS project here wraps up—the organization expects to be here for five years—ideally, the mission will continue through Cruz and other locals, who can demonstrate that providing better day-to-day care for these horses isn’t something that takes a lot of money.

“That’s what I do most every day, try to explain to people what we do,” says Cruz. “Show the people how to really take care of a horse. … It’s different in the U.S. to raise a horse than here. In the U.S., you have to have vaccinations. Here they let the horse go free, raise itself, do the best they can. … They don’t know much about vaccinating and all that stuff. But in the future, this island is going to be way better than it used to be.”

Some of the people who will help shape that future are currently quite small. They show up in droves to the horse festival The HSUS holds in January, high on a grassy bluff outside of town, an open space with bleachers that used to be the grounds for paso fino horse shows.

Kids arrive with parents and siblings and friends, sporting their bright yellow HSUS T-shirts, bringing their horses to the free veterinary wellness and grooming clinic. Kids of all ages, some who look to be barely into their double digits, come clipping up the narrow road to the grounds, some barefoot, some bareback, riding and leading pretty little horses they’ve gathered up from their grazing grounds. They wait patiently for their horses to get doses of medicine to treat parasites and listen carefully as the HSUS veterinary team examines the animals, treats any minor injuries or health conditions they see, and suggests basic follow-up care. The kids get new tack and supplies for their horses, new books to read and a glimpse into a new way to relate to the animals they’re growing up alongside.

On another part of the grounds, Sára Varsa, senior director of the HSUS animal cruelty, rescue and response team, shows one shyly smiling kid after another how to keep their horses looking great—how to clean their hooves, brush their coats, get burrs out of their manes.

Over the course of the two-day festival, 181 horses come in for treatment and grooming.

Varsa says the festival went even better than she’d hoped. She grins, recalling how even tough young guys, the few sulky adolescent types who initially seemed disinterested or sarcastic, showed tentative smiles as, for the first time, they learned to feed their horse a carrot.

“I swear I saw some pleasure there,” she says.

Later, out in the narrow streets of town near dusk, one of the HSUS Jeeps passes a little gathering of kids on the sidewalk. They’re standing around a boy and his horse, who’d been at the festival earlier and who got a lesson on basic hoof care from Varsa. The boy, who appears to be about 8, is bent over, his horse’s front foot in his hand. He’s picking a stone out of the sole, showing the other kids who have gathered to watch.

This is the way the change happens: in small measures. The brushing of a mane. The feeding of an apple. A grateful velvet nose, snuffling in a small hand that could one day shape the world.