Don’t buy into that doggie in the window

In new book, journalist investigates the cruel, complicated puppy mill industry

Journalist, Emmy-winning television producer and author Rory Kress loves her Wheaton terrier, Izzie, and originally thought nothing of purchasing the USDA-licensed pup at a pet store. But a few years later and a few years wiser, Kress embarked on a yearlong, nationwide investigation into the origins of pet store dogs like her own.

What she discovered—through interviews with USDA inspectors, leaders in the animal welfare field, behavioral scientists, veterinarians, psychologists, breeders and other experts—was that inhumane puppy mills supplying puppies sold online and at pet stores are not only prolific, but often legal and licensed.

In fact, a USDA inspection and license is just that—an inspection and a license. It’s not a stamp of approval, as many people might understandably assume, and it only indicates that a commercial breeder has met (or been advised of) the bare minimum standards of care outlined in the federal Animal Welfare Act. (Standards mandate food just once a day and living space only 6 inches larger than a caged dog’s body, for example).

The USDA’s self-described mission is to support America’s farmers, not to protect animals, says Kress. She found that state and federal breeder inspections might draw wildly different conclusions, indicating that USDA inspectors are failing to enforce even those bare minimum standards of care, and that even commercial breeders with multiple violations of the Animal Welfare Act can continue operating with a license.

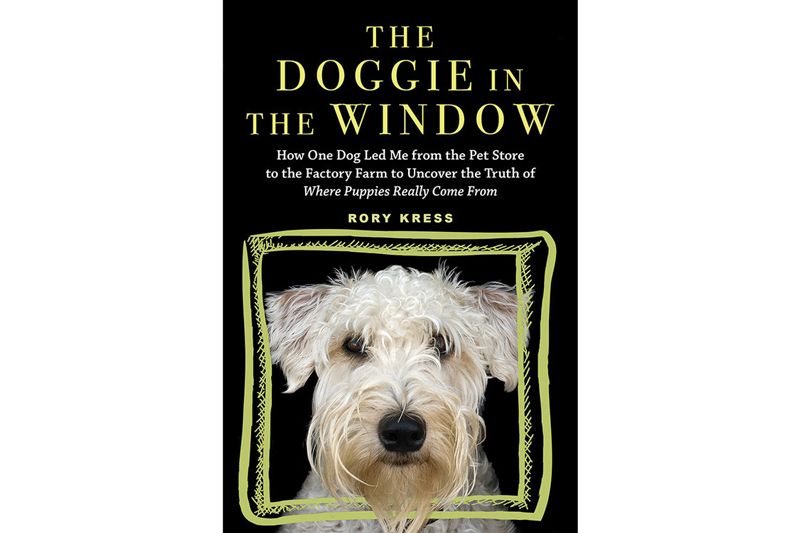

Described by Booklist as “a call to arms,” the resulting book, The Doggie in the Window, is a painstakingly detailed look at how puppy mill dogs make their way into our homes—and how the government fails, time and again, to protect human’s best friend. We chatted with Kress about her findings; the following is an edited transcript.

As you were researching your book, what was the most surprising thing you found?

I’m sort of a general reporter; I write about anything and everything, so I try to approach every topic, whether it’s a conflict in the Middle East or dog breeding, the way that a reader would, with this kind of fresh perspective: “I know nothing.”

I truly do feel as a dog owner, and really as a civilian, I really didn’t know that a lot of puppy mills—or what we think of as puppy mills—are legal, are regulated by the U.S. government, specifically by the USDA.

Right from the very beginning of the book I’m like, “These are the people who tell me what meat is safe to eat, what milk is safe to drink, what [food] is organic, and these are the people who are telling me ‘this dog was raised with good practices, this is a good actor, this is somebody who’s doing the right thing.’”

I think that most people have heard the story of the puppy mill. We’ve seen it on Oprah, we’ve seen it on The Today Show, we’ve seen it in all these different places, but no one really talks about the fact that puppy mills are legal.

It’s easy to have a lot of anger at illegal actors, and people who do these illegal things, but I think that’s much harder to chase down, because there are people who are going to do illegal things in every industry.

But when these are people who are inspected annually, held to a certain standard—whether or not you agree with the standards is a separate question—and regulated by the government, you start saying “Well, how is that possible?”

You talk about different types of people who buy dogs: the willfully ignorant, the deniers and the people who want to know the truth. Yet all claim to love dogs. Why do you think people who love dogs choose to remain ignorant about, or deny, their dogs’ origins?

Because they can. And that was one of the biggest things I found—how we are able to just force the reality we wish to impose on actual reality. How the system of commercial dog breeding in this country, and the way it’s been constructed—you couldn’t design it better if you tried. It’s designed to basically get the customer as far away from the truth of where their dog comes from as possible.

In the book, I eventually go back to where Izzie came from, and it couldn’t possibly be more different than the reality that was constructed for her in the pet shop, to the point that I came home and asked, “Who are you? I saw exactly where you came from. I saw your breed. These are probably descendants of the same line because we know puppy mills inbreed again and again and again. This is you six years hence, if you hadn’t been shipped off to the pet store.”

Once you bring that animal into your home—what happens to the human brain when you walk into a pet store or into a place where you’re choosing a dog, and what happens when you take that dog home, and how quickly that dog becomes a piece of your identity, and a piece of your family, and your life—it’s very hard to then ever see that animal as anything else. It’s just part of our brains. We’re just hardwired that way.

It seems like the USDA inspector you spoke with felt that it wasn’t his place to question the Animal Welfare Act, saying “our role is to enforce the law as it is now.” Why do you think inspectors aren’t more inspired to drive change when they’re seeing horrific conditions in puppy mills hundreds of times a year?

I speak to [USDA-APHIS regional director] Dr. [Robert] Gibbens multiple times, and I come back to him at the end of the book. I drop everything I found over the course of about a year, during which time I found some very damning evidence against the USDA—for example, state inspection reports filed the exact same day as federal inspection reports that paint a completely different picture of the same operation—among other things, I dropped these files on the table in front of him a year later and said, “What gives?”

And he really didn’t have an answer. I think a lot of it comes from: These are bureaucrats. I just think that the government moves very slowly. Ten generations of dogs can be already harmed before anybody even catches wind [of a bad breeder].

So it’s hard for them to kind of grasp the urgency and the immediacy when they’re bureaucrats, really, and they are kind of divorced from it.

In Gibbens’ case, I guess what struck me as the most troubling is he’s a veterinarian. He’s not just some administrator, which in some ways I could be like, “OK, you don’t necessarily get it.” He’s somebody who is a veterinarian and a pet owner, somebody who should understand exactly how painful these conditions prescribed in the Animal Welfare Act are.

Why do you think the USDA is so reluctant to bring the Animal Welfare Act in line with current science on dogs’ mental and physical needs?

Based on my findings as a journalist—because I have to come into this as unbiased as possible, beyond “I’m a pet owner, and I love my dog”—based on my findings, I do believe that there’s just a lot of shared interest between Big Agriculture and the USDA and, as I found, commercial breeding falls under agriculture, inexplicably I would say. I think it’s really hard because there is a really strong bond between the USDA and Big Ag, and there is shared interest, and these are the people that pay [the USDA] for licenses.

The people I interviewed said, “It’s not the Animal Welfare Act, it’s the keep ‘em in business act.” You reform that act, and a lot of people go out of business. You or I might say they shouldn’t be in business to begin with, but on the other hand, there is this funnel to public interest groups like Protect the Harvest, things like that. There’s this money there, and if you follow it, you see it.

Missouri is really the epitome of that very question right there. We saw that [in 2011] when the [Canine Cruelty Prevention Act] there came about to reform the state laws, and Big Ag marched in. All of these national agricultural interest groups marched in.

Why? Because one of its provisions in the ballot measure was to cap the number of dogs in a breeding facility at 50. It seems reasonable enough, 50 seems like a hell of a lot of dogs to me, it takes everything in me to make my one dog happy—OK, that’s just me, who’s to say—but all of these farmer’s interest groups, lobbyists, poured into Missouri with TV, radio, media buys to say, “This can’t happen. There can’t be a 50-dog cap.”

Why? Because they’d rather have the fight over dogs than they would over cows, over pigs. Because that would put all of those [industries] out of business. You think there’s money in the millions of dogs put out by USDA-licensed facilities every year, [but] there’s a heck of a lot more money in pork, in beef.

So if you put a 50-dog cap on a breeding facility regulated by the USDA, well, at some point you can also do that down the line, they thought, with cows. So in order to keep this ballot measure and make some of the provisions better for dogs already in these facilities, [former assistant attorney general of Missouri] Jessica Blome, she basically said we have to get rid of the 50-dog cap, knowing that that was the only way to [get the law passed.]

Animal welfare advocates were not all pleased with it. There are shades of grey on both sides, but the feeling was, we’re giving up something really valuable here, but otherwise, we’re not going to get provisions on how much water we can give these animals every day, we’re not going to get provisions on cage size, [provisions] that they knew immediately would make some difference.

And to be fair, the Canine Cruelty Prevention Act, once it did go over, had a major impact on how many breeders were able to stay in business. Now, is it a fabulous law that has created a wonderful state for dog breeding? No. The number one state on [the Humane Society of the United States’ list of bad breeders] the Horrible Hundred every year is Missouri. But hundreds of dog breeders did go out of business, so something did change.

You say in your book that it’s often the local laws that truly affect puppy mills.

Thirty-five states do have some sort of state-level regulation, but without state inspections, without state inspection reports and actually carrying out fines, many of those don’t really mean much.

Missouri does actually have state inspectors, and that was a big point that I was able to underscore when I went back after a year or so of investigating, I was able to say [to Gibbens], “Your investigators were at John Doe’s facility on the exact same day [as state inspectors]. Here are the Animal Welfare Act violations that they found. Your inspectors went there and left.”

So at least they left a paper trail where they could show the USDA wasn’t doing enough. Most states don’t have that, unfortunately, and even Missouri is trying to get rid of it, every year. Every year [we] have to fight the state capitol to keep those records publicly accessible. They want to completely hide them.

Based on your research, were you surprised when the USDA removed complete breeder inspection records from its site in 2017?

About a month before my [book] manuscript was due, I had to rewrite the entire book because I did not foresee Trump coming in and within 16 days of his inauguration pulling [the records]. There wasn’t even a USDA secretary yet.

Previously I’d spoken to Brian Klippenstein, who ran Protect the Harvest, and who then became kind of the de-facto transition head for the USDA at that point. Looking back on my conversations with him, six months before that transition and six months before the election was won, I could see then, in hindsight, see the writing on the wall from some of the things he said to me.

However, when it happened, I was as surprised as anyone and horrified. I had written the whole book with the impression that the inspection reports weren’t enough and that they were misleading the customer, but at least you could know if somebody had a license. At least you could know where to even begin your search.

But now we don’t even know that. The files that have been restored, I can’t search even the breeders that I know are in operation today. Keep in mind what these are for—the public. For whatever reason, human nature, people are going to buy dogs [rather than adopt]. Fine. But how can we minimize the damage of that wrong thing?

If I’m going to buy a dog, and I want to do my due diligence, and I want to do the right thing, if I want to search, there’s no way to even do that. If you do want to be a savvy, smart, empathetic thoughtful buyer, you can’t. If the government’s going to pick up the mantle of protecting these animals, and inspecting these animals, and regulating this industry … you want it to be something you can have some faith in.