How housing insecurity impacts shelters and rescues

With an estimated 8.4 million homes behind on rent, the end of the federal eviction moratorium has varied impacts on animal welfare organizations

Renters were supposed to be protected from eviction until October 3, 2021. But in late August, the Supreme Court struck down the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s federal moratorium on eviction. Fears about a wave of evictions that had been circling the country for months seemed likely to come true. So far, that hasn’t been the case, but evictions are rising, and the threat still looms. In some localities, shelters, rescues and other animal welfare organizations began to see an impact.

The current evictions landscape

There’s no national database on evictions, so the current scale of evictions across the country is difficult to quantify. Experts also note that the eviction data we do have may understate the problem as tenants are sometimes removed from their apartments illegally or without going through a formal proceeding.

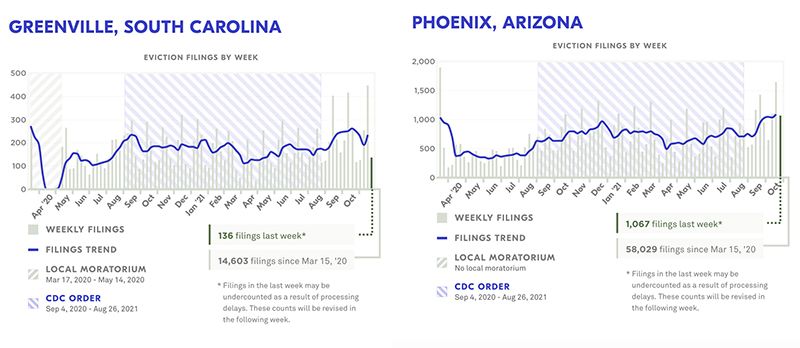

The Eviction Lab at Princeton University tracks eviction data in six states and 31 cities. Generally, their data shows that cities with weaker protections are seeing a rise in evictions, while cities with stronger protections are seeing similar rates to when the moratorium was in place. Areas where evictions were a major problem pre-pandemic seem to be hit especially hard.

In general, since the moratorium ended, eviction rates are rising—but slower than expected. There are a variety of reasons for this: Some localities implemented additional protections, such as eviction moratoriums and diversion programs; some tenants received government funding for rental assistance, or their landlords have held off on an eviction in the hopes that rental assistance will come through.

This doesn’t mean a wave of evictions won’t occur soon. A recent survey by the U.S. Census Bureau found that almost 8.4 million households are behind on rent, and over 3.5 million people said it was “very likely” or “somewhat likely” they would be evicted from their apartment in the next two months. State and local eviction protections may expire in the coming months, as well. According to the Urban Institute, around 37% of U.S. renters live in areas that have local eviction bans or are postponing evictions pending rental assistance.

“The eviction process in Georgia—and Atlanta specifically—is fast, cheap and easy for landlords to get a tenant out. There are very few protections.”

—Cole Thayler, co-director of the Safe and Stable Homes Project for the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation, and the co-founder of Paws Between Homes

How shelters and rescues have reacted

Cole Thaler works at the intersection of housing issues and animal welfare in Atlanta. He’s an attorney and co-director of the Safe and Stable Homes Project for the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation, and the co-founder of Paws Between Homes, an organization that helps pet owners losing their housing. Since the moratorium ended, Thaler has seen a rise in evictions in Atlanta. “It’s open season for landlords to go ahead with evictions,” he says.

Even before the pandemic, Atlanta had one of the highest eviction rates in the U.S. “The eviction process in Georgia—and Atlanta specifically—is fast, cheap and easy for landlords to get a tenant out,” he says. “There are very few protections.”

Paws Between Homes used to receive around seven calls a week for help, but in the last three months, it received five to six calls a day. Thaler says he can’t attribute the increase solely to the ending of the federal moratorium as the organization has been ramping up its outreach efforts. But he notes that some callers specifically mention the ending of the moratorium as the reason for their eviction.

Five hours away from Atlanta in rural Georgia, Karen Talbot, founder of Animal Aid USA, has also seen an increase in pet owners facing eviction. Her organization transports homeless animals from Georgia to rescue partners for adoption and helps pet owners in rural Georgia.

The area is low-income, and most people rent their homes. She gets about one call a week from a pet owner facing eviction. During the moratorium she would occasionally hear from pet owners facing eviction, “but it wasn’t anything like it is now,” she says.

Next door to Georgia, South Carolina has the highest eviction rate of any U.S. state. The state also is struggling with an overcapacity of animals at their shelters—a problem so severe that South Carolina shelters declared a state of emergency in August.

Samantha Brooks, director of operations at the Humane Society of Greenwood, says her shelter is experiencing overcrowding partly due to people being evicted. Since the federal moratorium ended, around half of the animals surrendered were due to eviction. While the moratorium was in place, that number was less than 10%.

Brooks thinks her area is experiencing this issue more acutely than other parts of the state: In Greenville, South Carolina, Michelle Simmons, division manager of the Greenville County Animal Care, hasn’t seen an increase in pet owners reaching out for assistance due to eviction.

Similarly, in St. Louis, the Animal Protective Association of Missouri hasn’t seen an increase in pet owners seeking assistance due to eviction. Kitty Lawrence, the organization’s community programs manager, says this trend may change once local moratoriums end.

In preparation for the ending of the federal moratorium, Arizona animal welfare organizations created the Pet Housing Help AZ Task Force to connect people with housing resources, as well as a foster care network for people seeking temporary housing for their pets.

Since the moratorium ended, Arizona Humane Society’s data shows evictions comprise a small number of owner surrenders and calls to its Pet Resource Center. The shelter has seen an increase in applications for its Project Home Away from Home program—which provides temporary foster care for pets whose owners are in crisis—in recent months.

In the five-month period from June to October, the shelter received 140 applications citing housing instability as the reason for needing temporary foster care, compared to 52 applications from January to May.

The ending of the federal moratorium isn’t the sole cause; the organization received more applications citing housing instability from July to August of this year than September to October. Rather, pet owners faced a myriad of housing issues.

“I think we always see housing instability, but not to this percentage,” says Lindsay La Pre, manager of the Arizona Humane Society’s Pet Resource Center.

Housing instability is a longstanding problem

Housing instability is one of the most common reasons people surrender their pets. Multiple organizations said it was a major reason pet owners reached out for assistance in recent months.

It’s not just evictions: Housing and rental prices have been surging, and the inventory of homes for sale is at a record low. The housing market boom has been lucrative for landlords and homeowners willing to sell, but has displaced pet owners as rental units are sold, says Talbot.

Brooks has seen a similar problem. “Here in my town, we often have a complex that is privately owned and then they sell it to a rental agency and so the rules change,” she says. “And now everyone who lives there has to get rid of their animals. We’ve had that happen quite a few times.”

After being displaced from their homes, pet owners often struggle to find affordable and safe housing that allows their pets, which is exacerbated by highly competitive rental markets in places like Phoenix.

Exorbitant pet fees—in the form of pet deposits, monthly pet rent or both—add to the challenge. In Texas, there are no regulations on how much nonsubsidized properties can charge for pet fees. Lauren Loney, Texas state director for the Humane Society of the United States and a former housing attorney, says pet fees can be as high as $800.

Lindsay Hamrick, HSUS director of shelter outreach and engagement, says the long-term goal is to pass policies prohibiting pet fees. “The issue of pet rent and fees separates so many loving families,” she says. “While local shelters are building programs to subsidize those costs to keep people and pets together, it’s only a Band Aid solution to a discriminatory practice.”

People displaced from their homes during the pandemic are also entering a highly competitive rental market in places like Phoenix. Even if they find a place willing to take pets, another applicant may swoop in and offer to pay a higher monthly rent, says La Pre.

“It’s really, really unfortunate, but more so for those who are truly in crisis and don’t have the funds to be competitive.”

“Here in my town, we often have a complex that is privately owned and then they sell it to a rental agency and so the rules change. And now everyone who lives there has to get rid of their animals.”

—Samantha Brooks, Director of Operations at the Humane Society of Greenwood

How to serve communities holistically

Although housing issues and animal welfare are interconnected, Thaler says the two fields are often siloed from each other.

“If we want to serve our communities holistically, to keep pets and the people who love them together in safe and stable housing, then animal advocates need to learn about housing challenges and opportunities, and housing people need to learn about animal resources,” Thaler says.

Shelters and rescues can bridge this gap by learning about the barriers pet owners face in seeking help, such as feelings of shame or fear of judgment, says Loney. These fears can also prevent pet owners from disclosing that they are facing an eviction. Without in-depth conversations, shelters and rescues may be missing information that could help keep pets and owners together and failing to understand the full scale of the issue.

“Data collection can be tough, but the key is for shelter staff and volunteers to engage people with respect, dignity and patience,” says Amanda Arrington, HSUS senior director of Pets for Life. “People often won’t feel comfortable disclosing personal information right away. It can take time and trust for people to open up and share.”

Hamrick notes that data collected by shelters and rescues does not capture all pet owners facing eviction.

“While shelter statistics are a helpful guide, we know that many people rehome their pets with family members, friends and neighbors to prevent them from ever entering the sheltering system,” says Hamrick. “Even when shelter intakes don’t reflect large spikes in surrenders due to evictions and a lack of pet-friendly housing, we shouldn’t assume that families are not being displaced from their pets.”

Although the impact of the ending of the federal moratorium on evictions is difficult to quantify, it is clear pet owners are suffering the trauma of being evicted from their home during a pandemic while trying to stay with their loving companions.

Talbot has seen firsthand the impact of helping pet owners facing eviction. Years ago, she helped a woman and her 5-year-old daughter keep their parakeet after their landlord told them they needed to pay a pet deposit and monthly pet fee to keep the bird. The family couldn’t afford it, so Animal Aid USA paid the deposit as well as the monthly pet fee for a year. The woman told Talbot she would never forget what she did for her family and to this day still sends Talbot pictures of her daughter playing with the parakeet.

“If you have a good home for a [pet] and it’s just a matter of a dumb security deposit, we’ll take care of it,” Talbot says. “Keep that animal where it needs to be.”