Humans of Animal Advocacy: Patrick McDonnell

MUTTS cartoonist makes good on his pledge to free Guard Dog and discusses his creative process

Originally, Patrick McDonnell thought he needed a bad guy.

A few months after he began drawing his syndicated comic strip MUTTS in 1994, McDonnell mulled creating “some bully in the neighborhood” whom the strip’s main characters, Earl the dog and Mooch the cat, would have to deal with.

He started sketching the new character, a muscular, square-jawed dog with a studded collar. In one sketch, McDonnell added a short, heavy chain, which quickly changed his vision.

“As soon as I drew that,” McDonnell recalled in a recent interview with HumanePro, “I said, ‘No, no, this guy’s not a tough guy. He’s not the villain. He’s a tragic character.’”

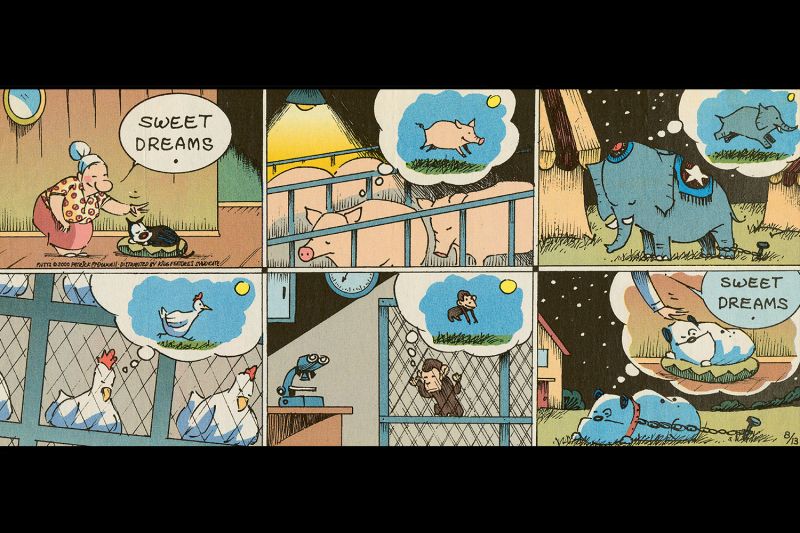

Guard Dog was born, and for nearly 30 years his situation tugged at the hearts of MUTTS readers. Chained day and night in a suburban backyard, he endured loneliness and neglect but never lost hope of someday living indoors and sleeping in a cozy dog bed.

In his 2019 book The Art of Nothing, McDonnell says that Guard Dog is about more than a neglected dog. “He represents the cruelty animals endure at the hands of humans. He also represents the cruelty we do to ourselves, staying chained to our old unconscious ways of thinking.”

The cartoonist promised that one day, Guard Dog would be freed.

In late 2023, McDonnell took the plunge. Over a seven-week storyline (the longest in MUTTS history) ending in December, Guard Dog is abandoned when his family moves away. In failing health, he’s discovered by Earl and Mooch, joined soon by Doozy, a good-hearted young girl who frequently visits him. Earl’s owner, Ozzie, arrives and unhooks Guard Dog’s chain. Taken to a local animal shelter, Guard Dog gets medical treatment and, after his stray hold, is adopted by Doozy’s family and renamed Sparky.

“And he actually gets to go inside a house and stay warm for winter and has a totally new life,” McDonnell says.

While some readers and animal welfare groups had urged McDonnell to keep Guard Dog chained as a reminder of animals’ plights, the time seemed right for the character’s next chapter in life, McDonnell says. “I’ve been promising it for a long time,” he notes, adding that the initial fan reaction has been overwhelmingly positive. “When are you going to free Guard Dog?” was often the first question asked at McDonnell’s in-person talks. “So I did it,” he says, “and I’m really pleased he’s finally free.”

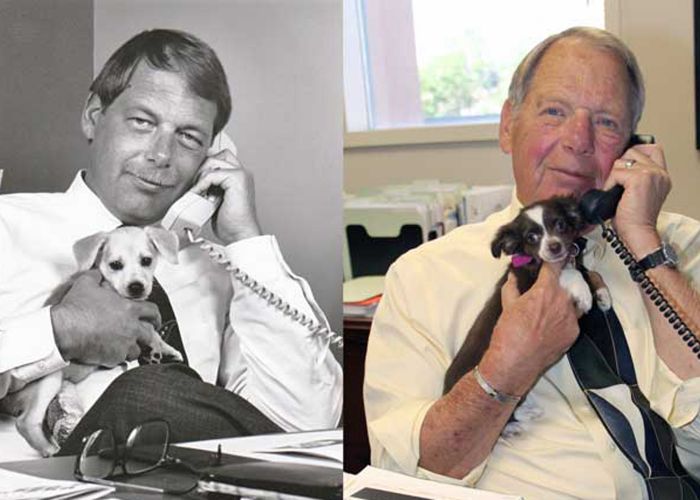

A lifelong animal lover, McDonnell served for 18 years on the board of directors for the Humane Society of the United States. The experience opened his eyes to the many ways animals suffer at the hands of humans, he says. “My empathy and compassion became larger, and I realized I could be a voice for the voiceless, with MUTTS being a good place to tell some of these stories.”

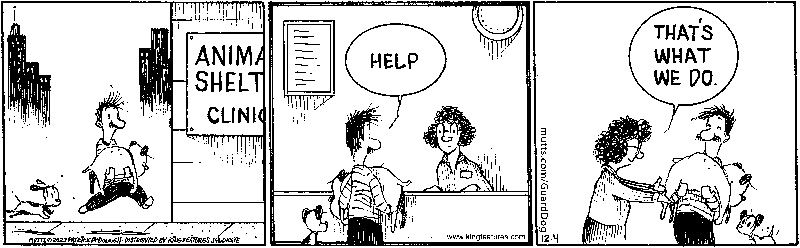

Over the decades, MUTTS has highlighted a variety of animal protection issues, including pet homelessness. For two weeks every year, McDonnell devotes his strip to “Shelter Stories” about animals in search of homes and potential adopters in search of companions. It’s his way of promoting shelter adoptions and expressing his admiration for the people who work in shelters and rescues.

“I’m working with animals in pen and ink, and they’re working with the flesh-and-blood ones,” McDonnell says. “They are the real heroes—all the people who dedicate their lives to helping those critters.”

In this edited interview, McDonnell shares some thoughts on pets, animal welfare and the goals of his art.

How did you get the idea to introduce animal welfare themes into MUTTS? Was it always your intention to do something more than just a gag strip about animals?

When I first started MUTTS, I wanted the animals to be more animal-like than most comic strips, and I wanted to play up that special bond we have with our pets. I had just gotten my first dog, a Jack Russell terrier—named Earl, who was the inspiration for the strip—and I knew if I could capture any of his joyful energy it would be a good strip. I was trying to explore that aspect of dogs and cats in comics and to see the world through their eyes.

After doing that for a while, I realized a lot of animals have it really tough. In the beginning it was centered on homeless dogs and cats. But the real catalyst for me was that the HSUS asked me to be on their board. Through that experience, I learned in great detail the suffering of animals on this planet.

The strip has very gentle humor and a lot of puns, so in some ways you’re swimming against the tide of humor in contemporary pop culture: MUTTS isn’t snarky, it’s not political, but you’ve found a big audience.

In this day and age, people are looking for a little positivity. I became a cartoonist because of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts and feel that, if I could give any of that joy back to the world, I’m doing my job. People need more joy and kindness.

I collaborated on a book, Guardians of Being, with Eckhart Tolle, the spiritual teacher who wrote The Power of Now. Tolle calls dogs and cats “guardians of being,” meaning that our dogs and cats are keeping a lot of us sane. He says they bring us “into the now” and away from our fears and anxieties. Our dogs and cats do that, and I hope MUTTS does that. Spreading a little kindness.

In your 25th anniversary book, The Art of Nothing, you mention that you like to pare your comic strips down to a point where there’s nothing left but love. Talk about that less-is-more approach.

Doing a daily comic strip, there’s so little space. My dailies are generally three panels, not much room, so you have to get to the essence of things. I compare it to haiku poetry. When you keep whittling away, what’s left? The only thing that is real is love. I see these little comic strips as little prayers, little haikus, a moment for the reader to experience joy.

MUTTS isn’t completely mainstream: You’ve used the strip to raise awareness about factory farming, seal slaughter and other hard-hitting animal protection issues. Is the strip a little subversive even though the humor is very gentle?

It’s amazing: I’ve been doing this for almost 30 years now and received very few negative emails about that. It’s like walking a tightrope. I don’t intend to be preachy. The comic needs to be entertaining, but I also want to get those messages out. A daily comic strip is a strange way to make art. When it was mainly available in physical newspapers, it was the first thing you read in the morning. It’s as if those strips become part of your family. Because of that, to me it’s more like a conversation around the kitchen table, and I’m able to bring up topics in a friendly manner.

It must be very gratifying to merge your art with your passion for helping animals.

Nothing makes me happier than when I get a letter or an email saying I inspired someone to go to the shelter and get a new companion, or a letter from a young kid who says he’s gone vegan because of MUTTS. Those are highlights for me; that makes it all worthwhile.

Listen to Patrick McDonnell’s recent interview on Humane Voices, the official HSUS podcast.