All about that (data)base

How to refine or replace your donor tracking system without getting lost in the data

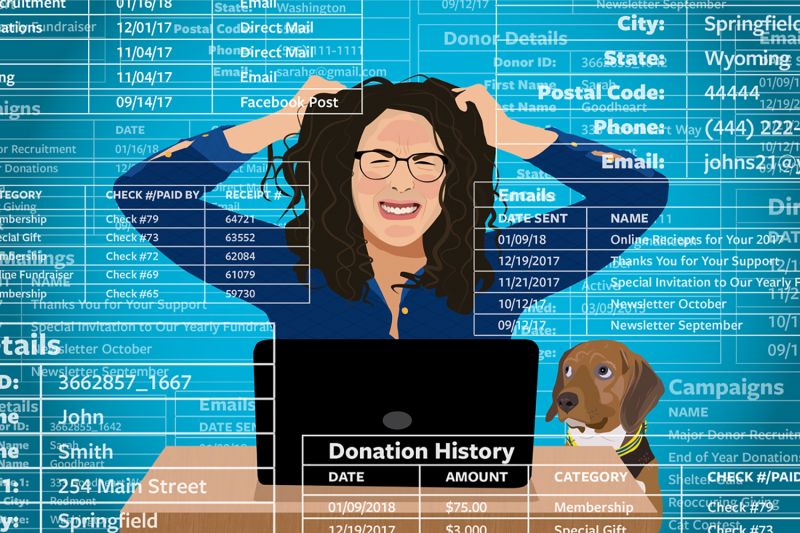

Are you frustrated with your organization’s donor database system?

Perhaps it pulls records of deceased donors for event invitations, fails to include “in honor” donations in lists for acknowledgment, or is unable to note connections between constituents. Maybe a seemingly simple report on cultivation activity takes countless aggravating hours, and there’s no seamless way to share information with your shelter’s other systems.

Faced with these and other problems, many of your animal welfare colleagues have gone through a complicated process to evaluate whether a new database was necessary and, if so, how to proceed with a purchase.

“I inherited an inefficient and ineffective database,” says Meghan Scheibe, director of development and community engagement at the Lawrence Humane Society in Kansas. “It was time-consuming and counterintuitive, especially with reporting.”

With her organization moving toward a capital campaign, Scheibe wanted a system that could accurately handle pledge payments and reminders, reduce duplicative data entry and provide more help with event administration by recording sponsorships and table seating.

She made a list of needs and wants while keeping in mind that “no one system will do everything perfectly.”

And, for the most part, she and her staff have been happy with the change. The new system has significantly reduced the amount of time they spend on data entry. “It lessens the need for human involvement and opportunity for human error,” Scheibe says. “We can now do so much more with reporting.”

But the process of choosing and transitioning to a new system wasn’t quick or easy. It involved six months of analyzing the shelter’s database needs, comparing potential replacements (and an array of often-confusing price structures and functions), communicating with vendors, testing the top candidates, training staff and managing the changeover.

“It’s an enormous undertaking if done well,” says Brad Shear, executive director of the Potter League for Animals in Newport, Rhode Island.

Three years ago, when Shear was CEO of the Mohawk Hudson Humane Society in Albany, New York, his development team had outgrown its system because the donor population had burgeoned. Ultimately, Mohawk Hudson switched to a new package, but the magnitude of the task has led him to back-burner a search for a new database at the Potter League.

While there are certainly good reasons to change systems, and the long-term benefits can justify the work involved, Shear advises a hefty dose of realism. A new program is unlikely to be the hoped-for panacea, he says. “Be careful not to assume that everything you dislike about your current system will suddenly be solved and everything will now be easy.”

“Choosing and transitioning to a new database system is “an enormous undertaking if done well.”

—Brad Shear, Potter League for Animals

System check

In the search for a better database system, many people start by listing problems with their current software and thinking of solutions they want in a new product.

But Robert Weiner of Robert L. Weiner Consulting in San Francisco says there might be a better beginning point. Weiner, who has decades of experience advising nonprofits on technology issues, suggests first appointing a project leader, such as a development director or IT director, to coordinate the evaluation of your current system and potential replacements.

“You will need to know from the outset who will make decisions, who staff will need to talk with, and who will prioritize requirements before bringing together stakeholders, especially direct users of the database,” he says.

You should also be clear about who will be making the final choice. If, for example, the CEO will likely choose a donor software program based on personal preference and will override the recommendations of others, then such politics should shape the search process from the beginning, Weiner says.

When leadership of the initiative is established, start engaging other staff in the effort. Shear recommends holding listening sessions with the people who directly enter data during their day-today work.

Giving everyday users a strong voice in the process will show respect for opinions, provide the most informed information and feedback, and secure buy-in for the final decision, he says. “Anyone who has a piece of the puzzle should be part of the conversation.”

Out with the old?

Once you have a strong idea of what your organization needs from its donor database software, take a close look at your current system, including who’s using the database and how they’re using it. It could be that the computer system isn’t the problem.

“Software alone will not solve complex problems,” Weiner says. “You must have the correct people, policies, procedures and business processes in place.”

When one of his clients says they want a new donor database, Weiner kicks off the effort by talking with system users, their supervisors and other staff members who rely on information from the system to determine if the existing database is truly problematic.

Team members may need additional training—and lots of it—as well as add-ons to the current package. Management should review whether staff are entering data correctly, have the appropriate skill level for the current program and are motivated to learn new methods.

Retraining and upgrades might be less exciting than a gleaming new database, but they can be far less expensive and time-consuming than a conversion.

“Take a serious look at your current product,” advises Joe Lisella, director of development for Marin Humane in Novato, California. “It will only be as good as what you put into it.”

A few years ago, Lisella was considering a switch to a new system when he recognized there was significant in-house expertise with the current product. While discussing problems with his vendor, he learned the company was planning an upgrade. His crew later decided that retention of the current package was the shelter’s best option, and the organization’s IT leaders were grateful to avoid a conversion.

Rich Anderson, executive director and CEO of the Peggy Adams Animal Rescue League in West Palm Beach, Florida, came to a similar conclusion in his search for solutions to a database system that “was frustrating us more and more.”

Anderson discussed the challenges with staff and asked for feedback on what they would like to see in a possible new product. He then sat down with the current database vendor to review point-bypoint what they needed from their platform. Happily, the company responded by saying solutions to many of his requests were already in the pipeline.

Anderson also suggests talking with other customers of your current vendor to see how they have addressed challenges with the product. “They are often glad to share their experiences,” he says, “and it’s smart to get connected to them.”

Plenty of choices

If you’ve determined that a new system is necessary, your next step is to identify potential replacements. The good news is that the marketplace is bursting with options, ranging from the basic to the highly sophisticated. They include not only a variety of donor-centered systems but also constituent-relationship management software to manage information on all the people and businesses your organization interacts with, such as volunteers, clients, donors and more.

The bad news is that you can easily get bogged down when comparing different system features, overall ease of use, available training and customer support, and numerous other variables.

Weiner advises asking staff about software they’ve used at previous organizations and talking with staff at other shelters and nonprofit development offices. Ideally, you want to check with similar-sized organizations that have comparable budgets, he says. “Their needs may be similar to yours, so you will want to learn about their solutions.”

While such conversations can point you to some solid choices, you still need to do your own research and testing with your organization’s needs in mind. Some common mistakes in choosing a new system, Weiner says, include not making informed decisions, picking systems simply because they were used at a previous job, choosing a vendor based solely on a discount, and selecting a system used by another organization even though the other nonprofit has different needs.

Of course, cost will likely be a big factor in your choice. Whatever your budget, it’s important that everyone involved is aware of the limits so you don’t waste time analyzing products that are out of your price range. At the same time, Shear says, keep in mind that system costs “are all negotiable,” and you may be able to haggle for fewer modules and a lower price. Lisella warns against the allure of free donor databases: While they may fill the needs of a small organization, “you could end up paying an enormous sum to customize” the product.

Scheibe’s search for a new product started with a survey from TechSoup, a nonprofit that helps charities with technology challenges. The survey was a good way to “figure out what you need and what you can afford,” she says.

Scheibe eliminated some options because of cost and narrowed her search to two products with comparable pricing and features. With her final choice, she identified more savings by declining to have the new system talk directly to the shelter’s adopter and volunteer databases since neither group typically yields a large percentage of donors, she says.

“Add-ons can add up,” Scheibe adds. “Be wary of shiny bells and whistles that you may not need.”

“Software alone will not solve complex problems. You must have the correct people, policies, procedures and business processes in place.”

—Robert Weiner, Robert L. Weiner Consulting

Systematic review

Once you have your shortlist, take a deeper dive into each system. To determine if the program can accomplish what you need it to do, your team should be prepared to discuss and test various case scenarios with a fair degree of complexity, says Weiner.

At Mohawk Hudson, after discussing what modules and functions were necessary, Shear and his team settled on three finalists. They completed hands-on demonstrations, talked with the vendors and then reconvened to share their evaluations.

Lawrence Humane narrowed its list to two products and then launched into demonstrations via webinar and phone. Scheibe and her staff underwent two 30-day test periods for each of the finalists, using live shelter data. This entailed double-entering data in the current system and the one being tested, but Scheibe felt live testing was essential to see how the products would work “in real-world situations.”

While live testing may not be feasible if you’re planning for significant customization, Weiner notes, you still want to spend time navigating the basic package. If you can intuitively figure out the software without a lot of training, that speaks well of the program as a whole, he says.

Proper vetting of candidates should also include talking with current users, who can provide valuable information on a system’s strengths and weaknesses, the customer support provided and the ease of the transition process. Lisella recommends asking potential vendors for references who have been using the system for at least a year to ensure they provide a seasoned perspective.

Shear advises asking about the “happiness level” of development staff at organizations that have recently gone from your current system to the ones you’re considering. (Trade organizations like the Association of Fundraising Professionals can be a good place to find such contacts, says Weiner.)

“Add-ons can add up. Be wary of shiny bells and whistles that you may not need.”

—Meghan Scheibe, Lawrence Humane Society

All systems go!

Congratulations! You’ve made your choice and negotiated the specifics with the vendor. Your focus now shifts to training staff on the new software and coordinating the transition.

Any new database takes time to navigate and master, says Scheibe, so you should set aside ample time for staff training before you go live with the new system. The timing of the transition is also important, adds Shear. “Make sure you stay away from year-end and key events.”

For an efficient conversion, Weiner advises assigning staff to an implementation team and, if you can afford it, hiring a third-party IT consultant to help manage the transition. Depending on the level of support your vendor is providing, your implementation team may need to document new business procedures, design and test reports, and verify the data migration is accurate. As an added security measure, “you may also want to run the old database in simultaneous operation for one month or more,” Weiner says.

At Lawrence Humane, the changeover period involved a 10-day overlap with the old and new databases. During this time, Scheibe and her staff entered data in the new system but had their dependable backup.

At Mohawk Hudson, Shear’s team used a test database for training and watched webinars before launching the live system. For peace of mind, they paid to keep the old database for a month after the conversion.

A major factor in his “pretty smooth” conversion experience, Shear says, was working with the vendor to ensure old data was mapped correctly into the new system. Even name and address fields, he warns, can be surprisingly complex, depending on how data records are set up.

Scheibe also cites vendor support as critical to ensuring a successful and relatively stress-free conversion, and that’s another variable to consider when choosing a system. Vendors for many of the most popular products offer different levels of training and support at different price points. In Shear’s experience, opting for a high level of customer support is worth the additional cost, especially in the first year of the conversion.

After all, a new donor database system represents a major investment of time and resources, Shear says. “You want to get this right and not do it again anytime soon.”