Building momentum for pet-inclusive housing

Humane World mentorship program helps shelters tackle housing barriers to pet ownership

When Sharon Harvey, president and CEO of the Cleveland Animal Protective League, tries to understand the forces that can separate pets from their owners overnight, she doesn’t have far to look. The shelter sits in a gentrifying city neighborhood called Tremont, where fancy new condos that cost half a million to a million dollars—and related property value increases and tax hikes—are pricing out residents of modest means.

But some of the reasons owners struggle to care for and keep their pets only become visible after data about communities is collected and analyzed.

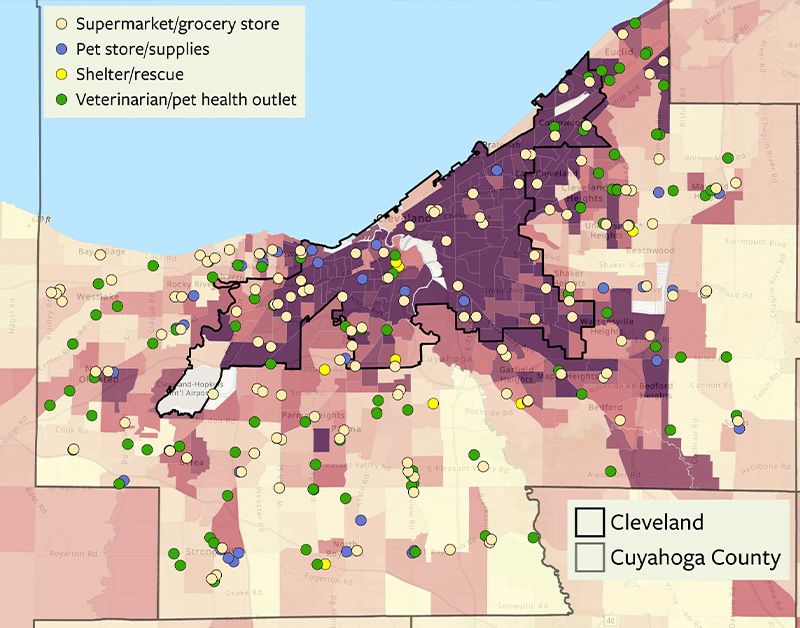

As part of its Shelter Mentorship pet-inclusive housing program, Humane World for Animals mapped the Cleveland APL’s service area to show income, race, the legacy of “redlining” practices that denied African-Americans access to affordable 30-year mortgages, and more.

The map Harvey finds most eye-opening is one that illustrates where pet care resources are available or absent: Scattered throughout the region her shelter serves are colored dots representing supermarkets, pet supply stores, animal shelters and rescues, and veterinarians. To the east of Tremont, across the river, in an area with a poverty rate of 26% or more, there are no dots. The neighborhood of Central/Goodrich-Kirtland Park is a resource desert that’s especially challenging for residents who own pets, because many don’t have cars.

“What the data shows very clearly is where there is a void,” Harvey says. “When people suffer, pets suffer.”

New tools for advocates

The pet-inclusive housing initiative, one of three focus areas of the Humane World Shelter Mentorship program, provides two shelters a year with $15,000 each in grant funding and advice from HSUS experts on how to respond when pet owners lose their housing and how to advocate for rental housing that allows people to keep their pets. Participants so far have been the Cleveland APL and Richmond SPCA in Virginia (2022); Greenville County Animal Care in South Carolina and the Houston Humane Society in Texas (2023); and ACCT Philly in Pennsylvania and the Animal Rescue League of Iowa (2024). The MSPCA (Massachusetts) and Harris County Pets (Texas) are also working with Humane World to gather data on how housing issues impact pet owners.

The end goal of the mentorship is to keep people and pets together, says Amanda Arrington, Humane World vice president of access to care.

Lack of housing is often given as a reason people surrender pets to shelters, says Jessica Simpson, Humane World senior specialist for companion animal public policy. People may become homeless, or they may not be able to find a landlord who will accept their pet. But the evidence for that at the community level has been largely anecdotal, she says. Now, in addition to mapping of community demographics, Humane World has developed a tool for collecting data on why people give up their pets so that shelters can understand how many surrenders are related to housing barriers. Shelters can use that information to lobby for changes in local and state policies and build safety net programs to keep pets with their families when possible.

More than 90% of rental housing has pet restrictions.

—2021 Pet-Inclusive Housing Report by Michelson Found Animals and Human Animal Bond Research Institute

In 2022, Humane World began training shelters on how to collect data, including how to engage with community members. Through surveys and research—gathering information from people surrendering pets, from renters in the wider community, and from local governments and landlords—shelters gain a detailed picture of how the affordable housing shortage affects people and pets.

They delve into questions such as the percentage of renters in their regions, the types of housing policies that are having the greatest impact, and who is most likely to be affected. They learn what kinds of fees renters with pets face; whether pet owners have had to surrender their pets to get housing; whether they have been asked to declaw or devocalize their pets; whether they face restrictions based on a pet’s age or breed; whether a surrendered dog has been declared dangerous by a court under municipal or state regulations; and whether insurance companies have cancelled policies based on the perceived breeds of dogs.

Simpson is working on making the data more useful for shelters by building local databases and creating dashboards so shelters can access and analyze the information. So far, the data show that the most frequent reasons offered for needing to surrender a pet are limits on the number of pets and breed restrictions. Pet fees are another frequent reason.

Fair housing for the entire family

At the Cleveland APL, animals given up by people because of housing issues represent just a small part of the shelter’s total intake, but their numbers have increased since 2020 because of rising rents and the loss of pandemic aid, Harvey says. In just the first three quarters of 2023, nearly 100 pets were surrendered to the shelter because owners faced issues with their landlords or lost their homes. Another 150 were surrendered because their owners needed to move.

“We have to take their animal. It doesn’t feel good…” she says. “That poor animal has no idea why they’re no longer with their family.”

Using the information from the pet-inclusive housing mentorship, the Cleveland APL helped craft the Pet Friendly Rental Act, which was introduced in September 2023 by a bipartisan pair of lawmakers. The act would give landlords tax credits of up to $750 per unit for up to 10 units per year if they agree not to discriminate based on size or breed and not to charge nonrefundable pet deposits or monthly pet fees.

While the bill failed to pass before the state legislature adjourned in December 2024, it's slated to be reintroduced this year. Harvey hopes it will encourage landlords who rent lower-priced housing to remove the restrictions and extra charges that force many people to give up their beloved pets.

Nearly 25% of people surrendering their pets cited housing restrictions as the reason.

—Michelson Found Animals Foundation and Human Animal Bond Research Institute

In the meantime, the Cleveland APL has used the demographic maps and other information from its mentorship to train staff on inequities that impact people’s ability to provide for their pets, says Arrington.

“When you’re in a shelter environment day in and day out, it’s hard to give people grace,” she says. “But now, instead of blaming individuals, staff show compassion and say, ‘I understand, they’re likely a renter, they likely don’t have personal transportation and their income is low.’”

The Cleveland APL has started partnering with legal aid to get referrals of pet owners with housing issues and has begun supplying pet food and cat litter to several community food banks, says Ayse Dunlap, vice president of operations. The shelter is also developing a safety net foster program based on a model developed by Lisa Gunter, assistant professor at the Virginia Tech School of Animal Sciences, who as part of the mentorship gave a presentation to shelter staff. Volunteers will foster the pets of people without housing for up to 90 days, until their owners can find a place to stay.

Until now, says Dunlap, the shelter encouraged people with housing issues to turn to friends and family. Now, thanks to the mentorship, the shelter will have more ways to help.