For community cats, a change is gonna come

A former ACO turned shelter veterinarian has a startling message: When it comes to stray cats, we’ve been doing it wrong

Back in the early ’90s, the Santa Cruz Sentinel did a profile of my shelter jauntily titled “From Canines to Constrictors with the SPCA.” The picture of me (above) ran with it, and whenever I happen across the story, I remember the pride I felt in that uniform (in spite of my regrettable cat-carrying technique. Note to former self: Next time throw a towel over the carrier!). I also remember the dedication I felt toward the animals in our care. I know a lot of you will relate to what I told the reporter that day: “I work with people. I like people. But the reason I do this job is because I love animals.”

For all my enthusiasm, I also talked to the reporter about the dark side of the job. That year, more than 4,500 animals lost their lives at that shelter. The cat I was carrying had only about a 25 percent chance of leaving alive. Had she been unsocialized, her chance would have been zero. Our policy was to euthanize feral cats immediately, so it would have been my job to march back to the euthanasia room, and perform that sad task myself.

And that’s something I did, with the most care and professionalism I could muster, too many times to count. I did this even though I loved cats, even though my nickname as a kid was “Little Kat” Hurley, even though my best friend growing up was an immense tortoiseshell cat named Pussywillow. I did this even though it broke my heart.

Why? Certainly not for lack of caring. Indeed, shelters exist because people care. They exist with a goal of protecting animals, preventing cruelty and suffering, promoting healthy, humane communities, and solving the problems associated with companion animal overpopulation. And they—we—have had remarkable success. On a per-capita basis, shelter euthanasia in the United States has reportedly decreased more than 10-fold since the early ’70s.

But if you look closer, you’ll see the news is not all good—especially for cats. Although some communities are doing much better, in my home state of California, the odds of a cat leaving a shelter alive are still only about one in four. Across America, outcomes for cats may be improving, but not nearly as quickly as they are for dogs. In some communities, feline intake and euthanasia continue to rise.

Why? For the answer to this question, we need look no further than the unowned cats sauntering through the alley behind the gym, loitering by the dumpster at the local fast food joint, or hanging around our own backyards.

The Community Cat Gap

Until recently, most sheltering programs simply didn’t focus on the role that unowned animals play in shelter intake and euthanasia. But to educate owners on the benefits of sterilization or training that might help them keep their misbehaving cat in the home, there has to be an owner getting the message. In order for adoptions to reduce shelter euthanasia, the animals concerned have to be suitable for a home environment.Feral and unsocialized cats defy these requirements. Often there is no caretaker to avail themselves of low-cost services or benefit from programs aimed at helping pets stay in their homes. No matter how long the stray holding period, there is no one to come looking for an unowned cat, and the number of unsocialized cats entering most shelters far exceeds the number of barn or alternative homes to be found. And the role played by these cats is far from trivial—in fact, researchers have estimated that the population of unowned or “community cats” missed by traditional sheltering programs might be as big as the population of pet cats in the United States. Gulp.

Knowing that euthanasia of healthy cats neither controls feline populations nor protects individual cats, there is freedom in realizing how little we have to lose.

Fortunately, there is great news hidden in this alarming data. Once we understand the role community cats play in shelter intake and euthanasia, we can begin to solve the problem. And we don’t have to wait decades to do it.

The fact is that some outdoor-living cats are already thriving in communities. Picking up and euthanizing a small fraction of them doesn’t serve any of the purposes for which shelters were formed. It doesn’t protect the cats themselves. It doesn’t help reunite lost cats with owners. It doesn’t protect other pets, wildlife, or human health. And it doesn’t help control feline overpopulation—if it did, we would have solved the problem long ago, when shelters were euthanizing 10 times as many cats as they are today.

Once we recognize this fact, we can just stop euthanizing healthy cats. And we can redirect our efforts at programs more likely to benefit cats and communities as a whole.

Rethinking Our Approach

Seriously? Just stop euthanizing healthy cats?

You might be thinking that sounds a little too easy. You might also be wondering, “If shelters stop euthanizing cats, won’t communities soon be overwhelmed by a feline population boom? Won’t birds and wildlife be decimated by a sudden superabundance of cats? Won’t the cats suffer and starve?”

I get it. I believed all those things when I was the one out there picking up and euthanizing cats, and these are questions that continue to arise. The answers lie in recognizing the limits of what we are currently accomplishing through shelter intake and euthanasia.

The strongest evidence, interestingly, comes from the very same science often used to decry trap-neuter-return (TNR) programs. While sterilization unarguably benefits individual cats and relieves nuisance concerns, statistical models tell us that 75 percent or more of a cat population needs to be altered to have any overall impact. Detractors of TNR argue that this level of sterilization is rarely attained, and argue for euthanasia as the logical alternative. However, the same statistical models predict that at least 50 percent of cats need to be euthanized to have any impact. So overall, neither approach will be effective unless a sufficient proportion of cats is reached.

The gap in most communities between reality and the level of euthanasia required for population control is staggering. In “The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States,” the study that triggered the latest round of controversy over cat predation, the authors’ calculations are based on an estimate of 30-80 million free-roaming unowned cats in the U.S. Currently it’s estimated that around two million cats are being euthanized nationally each year. To reach the 50 percent threshold, then, across the country we would need to euthanize 8-20 times as many cats as we are now. Would communities stand for—much less pay for—such a dramatic increase in cat killings?

We are clearly not euthanizing enough community cats to make even a negligible impact on the number of cats in the community or their impact on wildlife, community health, or feline overpopulation. If it’s not helping, it won’t hurt to stop. And in stopping, we can open the door to better ways to protect all human and animal members of our communities.

What About the Cats?

As shelter professionals and animal lovers, the welfare of cats is naturally of paramount concern. We hate to think of them out on the streets, hungry, coping with weather extremes, predation, cars, and all the other threats that confront free-roaming animals. However, data from shelters and TNR clinics reveals that the vast majority of stray and unowned cats are in good health, suggesting that these resourceful creatures have worked out some source of food and shelter. Several studies have documented survival rates for these cats at rates far higher than that of other small carnivores—and greatly exceeding the odds of survival in a shelter.

Of course, like any living being, cats are subject to hazards, illness, and eventually, the infirmities of old age and death. However, cats are the only species for which it is routinely argued that a certain death today is preferable, for the cat’s own good, to a possible hazard in the future.

So what now? Acknowledging the failures of a system in which so much has been invested may be initially discouraging, but it opens the door to consideration of new possibilities. Knowing that euthanasia of healthy cats neither controls feline populations nor protects individual cats, there is freedom in realizing how little we have to lose. With this in mind, there are two increasingly popular options to consider: sterilizing and returning cats to their habitats (shelter-neuter-return), or, as a last resort, limiting intake when spay-neuter-return is not an option. Over the last few decades, TNR has become well-accepted. In these programs, cats are typically trapped from their community habitat, brought to a spay/neuter clinic, then released at the original trap site. Regardless of the impact on overall feline population size, sterilization and vaccination of individual cats is clearly preferable to allowing those same cats to continue breeding unchecked.

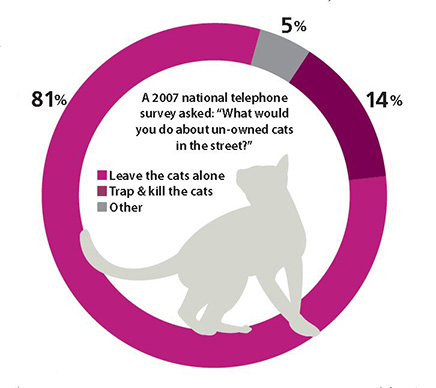

However, the notion long persisted that once admitted to a shelter, the option of sterilization and return was no longer a reasonable one. This may have been out of concern that citizens bringing stray cats to shelters would be vexed to see them reappear a few days later, albeit minus some reproductive parts and an ear tip. But the progress we’ve made in sheltering over the last decades has been accompanied by a vast shift in the public’s attitude toward pets. A recent poll found that more than three-quarters of Americans now believe that only sick and dangerous animals should be euthanized at shelters, and a great majority also believe that community cats should be left in place if the alternative is euthanasia. This gives us not just the freedom, but a strong mandate, to find nonlethal alternatives for healthy cats brought to the shelter.Recognizing this, more and more shelters are implementing shelter-neuter-return programs (aka SNR) to manage healthy stray cats that would otherwise be euthanized, either because they are unsocialized or because there are simply more cats entering than can be placed into adoptive homes. As in traditional TNR programs, cats are vaccinated, sterilized, and returned to the location where they were found; the only difference is the brief stop at the shelter. Spectacular success has been reported for SNR programs (read about one of them on p. 29), extending even beyond the dramatic reduction in euthanasia these programs achieve. Getting SNR cats in and out of the shelter quickly frees up time and space for other cats awaiting homes. Although SNR programs—like traditional TNR programs and euthanasia—may not impact feline population size overall, by definition they target those cats that are most likely to cause concern or annoyance to people. Perhaps that’s why SNR programs have led to surprisingly large declines in shelter intake, as well as a decrease in the number of cats found dead on the roadways.

Is SNR the Panacea?

Not so fast, you might say. What about shelters that can’t afford SNR? What if there is no veterinarian on staff, and no local clinic available to provide sterilization at a modest price? What if there is local legislation prohibiting sterilization and return of cats to their habitat? These are realities facing many shelters.

Fortunately, there is a third option: Don’t admit healthy cats if the result would be euthanasia of that cat or another to make room. In the majority of communities in the U.S., there is no legal mandate for shelters to impound every stray cat.

This idea was a hard sell for me at first. I “grew up” professionally at an open-intake shelter where we took pride in accepting every pet that came our way. Our fear was that cats would suffer even more dire consequences if we turned them away, regardless of how crowded the shelter conditions or how slim the chance for live release. But now we know more about community cats. According to the data we have, the vast majority of cats in a given community are never touched by a shelter, and the ones who do come in present as physically healthy. By admitting even a few in excess of the number we can care for and release alive, we compromise our shelters’ function and ultimately fail to serve cats to the best of our ability. Shelters that have eliminated intake of healthy feral or stray cats for whom euthanasia would be the likely outcome have found they have more time, energy, and resources both for the other animals in the shelter, and for building programs to better address the community’s needs over the long haul.If only some of these ideas can be implemented at first, they’re still worth pursuing. Think about starting small. If a few slots are available for SNR, even once or twice a month, a few feral cats can be admitted. When the SNR slots are full, alternatives can include referrals to the nearest clinic offering this service, as well as the many practical and humane strategies to coexist peacefully with community cats. Likewise, if even a few barn homes can be found, then a few unsocialized cats can be admitted, sheltered, and released alive. Meanwhile, the remaining cats can stay in the relative safety and familiarity of their community “home.”

An added benefit of allowing unidentified cats to remain where they are is that it will actually increase the chances of lost cats being reunited with their owners. According to a 2007 study by Linda Lord, cats are more than 10 times as likely to be returned to their owners by means other than a call or visit to a shelter. And cats living in communities also have a chance of finding a new home; multiple surveys have documented that people are more likely to acquire cats as strays than from a shelter or rescue.

Come Together

Perhaps the greatest benefit of allowing cats to remain in communities is that it gives every community member a chance to participate in the solution. Shelters have a long history of taking this approach when it comes to wild critters such as raccoons and opossums. Realizing the futility of trying to control these species through shelter admission and euthanasia, we guide people to other solutions. The same can be true for community cats: With a little guidance, many people will rise to the occasion, and find ways to coexist peacefully with the cats in their neighborhood. Without the illusion that euthanasia can eliminate the concerns associated with cats, wildlife advocates, public health officials, and cat aficionados alike can work together to find other answers. And while there will no doubt be some relentless complainers over this idea—as there are with any new policy—some great shelter wisdom applies perfectly here: “You’ll be criticized no matter what you do. You might as well be criticized for doing the right thing.”

I started this article with a reminder of what got me into this field in the first place—my love for animals. But I’ve come to realize I love people too. I love the people who do this challenging, rewarding, necessary, and sometimes heartbreaking work. I remember myself as a 24-year-old field officer, brimming with enthusiasm for my chosen profession. I think of how my heart ached for the cats we couldn’t save, and whose lives I ended with as much compassion as I knew how. I think of people still in the trenches, and I mentally multiply the number of cats euthanized by the toll each death takes on all of us. I picture the river of time, energy, space, money, and heartache our profession has poured into the seemingly unending task of sheltering and euthanizing healthy cats.

Then I imagine we just stop. We don’t admit one more healthy cat to a shelter than we can release alive. And I imagine that enormous river of resources and compassion diverted to finding other solutions, to spay/neuter services, to educating the public, to caring for domestic and wild animals, to finding ways to protect all the species we treasure. I imagine you, reading this article. I wonder what your role is and what it would mean to you if we could see a day when no healthy cat was euthanized in our shelters. I hope we don’t have to wait another 20 years to find out.