Helping under-resourced animal shelters transform their operations

By facilitating shelter-to-shelter relationships, the Humane World Shelter Mentorship program builds animal care capacity in rural and under-resourced communities

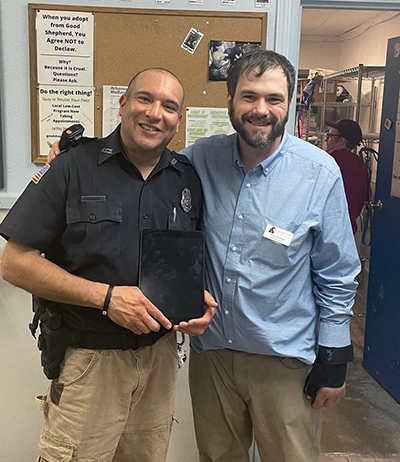

When Angel Rodriguez started as an animal control officer at Green Forest Animal Control in 2020, he completed all the department’s paperwork by hand. It was basically “stone and chisel and hammer,” he jokes. As the only employee in the department, he had plenty to do, and filling out forms manually took up a lot of time he could ill afford.

That would change earlier this year after Good Shepherd Humane Society in nearby Eureka Springs joined the Humane World Shelter Mentorship program and took Rodriguez under its wing.

Like Green Forest, Good Shepherd is located in a tiny town in Carroll County, Arkansas. But Good Shepherd, a private nonprofit founded more than 40 years ago, has more resources, including seven paid staff members, a low-cost spay/neuter clinic and two thrift stores that fund about 40 percent of its annual budget.

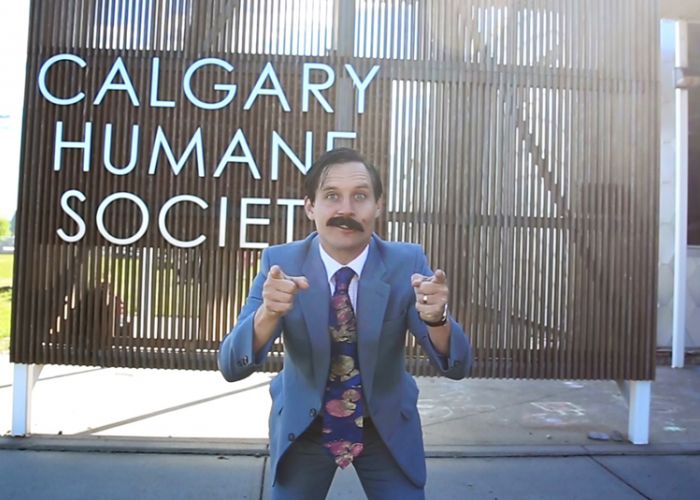

Cole Wakefield, Good Shepherd’s executive director, is passionate about increasing animal care resources in rural communities, so when he learned about the HSUS Shelter Mentorship program, he eagerly signed on as a mentor organization focused on regional capacity building.

He’s now mentoring groups in Arkansas and Missouri, but most of his work is with Rodriguez. Together, they’re exploring ways that Green Forest can grow its resources to better serve pets and people in its community. One of the simplest ways Wakefield has already helped was providing Rodriguez an iPad equipped with sheltering software so he no longer has to complete paperwork by hand.

Meeting the field’s evolving needs

For years, the Humane World Shelter Mentorship program (formerly known as the HSUS Shelter Ally Project) focused on transporting animals from small, overwhelmed organizations to ones with the capacity to take in additional animals. This model worked great for a time, but as other nonprofits also stepped into the animal transport arena, Lindsay Hamrick, Humane World director of shelter outreach and engagement, saw an opportunity to try something new.

She and her team assessed what obstacles shelters, rescues and municipal agencies across the country were facing and thought about where their expertise could have the most impact. They found three programmatic and policy issues to focus on: community cats, pet-inclusive housing and regional capacity building.

Under the newly designed program, which launched in 2021, shelters apply to the program and commit to focus on one of the three areas. Selected organizations receive support, guidance and a $15,000 grant from the HSUS to help build programs and change policies related to their focus area.

“Until the small agencies have enough resources to do the basics, they’re never going to have the bandwidth to tackle the root causes that land pets in shelters.”

—Lindsay Hamrick, Humane World for Animals

In the regional capacity-building arena, shelters serve as mentors to one or more organizations, helping them take their operations to a new level and become sustainable and resilient. “As a national organization, we can’t be in all those communities, nor should we be,” says Hamrick, noting that organizations rooted in local communities understand the needs of their area better than outside organizations.

By facilitating these shelter-to-shelter relationships, Hamrick and her team aim to address the disparity in animal care resources across the country. “There are just huge swaths of the U.S. that either have no animal services or their animal services are one part-time animal control officer who has no resources,” she says. “Until the small agencies have enough resources to do the basics, they’re never going to have the bandwidth to tackle the root causes that land pets in shelters.”

Building bonds

In 2022, the Humane Society of Charlotte in North Carolina mentored three local shelters to help build capacity in the Carolinas. “One of the things that I really liked about [the Shelter Mentorship program] was that it was very strategic in who the partners were and [that] it wasn’t just about transferring animals into our organization for placement,” says executive director Shelly Moore. “My interest had more to do with helping those organizations elevate their knowledge, skills, goals, exposure, expertise to become self-sustaining where they didn’t have to transfer animals out or that [the need for transfers was] reduced significantly.”

That said, Moore and her team used part of the grant money to transfer 235 animals from mentee shelters into their care and to assist animals with advanced medical needs. That type of immediate assistance opened the door for those relationships to grow, says shelter operations manager K.C. Thompson.

Expanding collaboration among local organizations is especially important in rural areas where resources are limited, says Wakefield. “Unfortunately, in rural areas, a lot of the support resources—like food banks and spaying and neutering, low-cost clinics and things like that—just don’t exist. That’s really what we’re trying to help the groups that we’re working with … see how we can leverage whatever limited resources we do have to get everybody to adopt a more proactive, in-the-community approach.”

Mentors help mentee organizations with everything from drafting external communications and marketing materials to updating vaccine protocols. Meanwhile, mentor organizations receive their own kind of mentoring from the HSUS team. Hamrick has monthly calls with mentor organizations to discuss any hurdles.

“We feel really strongly that we’re not coming in with a formula or prescribing anything; we want to talk with them about what’s achievable,” she says. Hamrick adds that since the mentorship program only lasts a year, they want to focus on setting a foundation for productive relationships between organizations that can continue long after the official mentorship period ends.

“I don’t see it as my role to step in and solve every problem that pops up. It’s more of helping enable the mentees to learn how to solve those problems on their own.”

—Cole Wakefield, Good Shepherd Humane Society

Overcoming obstacles

While mentees work to build their capacity, external factors can complicate efforts.

Green Forest Animal Control is in a rural town with fewer than 3,000 human residents, which makes it difficult to hire staff with animal care expertise. The department has been trying to hire an additional staff member for nine months with no luck.

It’s a problem Wakefield sees in many rural communities. Small towns already have a limited applicant pool, not many people have animal care experience, and it’s difficult to recruit from outside the community as the pay is often less competitive.

That’s OK, though, Wakefield says. He wants to focus on developing animal care skills and knowledge among community members who are interested in working in the field.

Rodriguez had no official animal care experience when he was hired but had a lot of passion and excitement about the role. Wakefield has brought Rodriguez to Good Shepherd to teach him about the organization’s protocols and best practices, and he used some of the grant money to send Rodriguez to animal care conferences and workshops.

The current sheltering crisis—where shelters and rescues across the country are experiencing spikes in intakes and decreased adoptions—also impacts mentors’ ability to transform operations in struggling shelters. “Maybe we can’t focus as much on the more community-based programs because we have to get these guys rolling at their base level,” says Wakefield. “It makes it harder to make that sort of shift into proactive action because the reactive part of sheltering is just so overwhelming right now.”

In the face of these ongoing challenges, local connections are especially important. Rodriguez has taken everything he’s learned to heart and is excited to continue expanding the services he can offer his community. With the help of Good Shepherd and other organizations, Rodriguez started distributing pet food and cat litter to the local food bank, providing a vital service for low-income residents struggling to afford pet supplies.

Wakefield and Thompson offer the same advice for future mentoring organizations: Listen to your mentees rather than simply telling them what you think the solutions are. “I don’t see it as my role to step in and solve every problem that pops up,” says Wakefield. “It’s more of helping enable the mentees to learn how to solve those problems on their own.”