Our presidents, their animals … and us

White House pets reflect our ever-evolving relationship with animals

It’s March 2021, and then-White House press secretary Jen Psaki is holding a press conference. Newly elected President Joe Biden has been in office for less than two months, and the hard-charging White House press corps, always on the lookout for broken political promises, wants answers about the pressing issues of the day.

“We were promised a cat,” one reporter says to Psaki. “What happened to that?”

Psaki throws up her hands in what appears to be mock exasperation.

“I don’t have any update on the cat,” she replies. “We know the cat will break the internet.”

Well, not quite. Though the Bidens’ long-awaited new cat, Willow, certainly attracted a lot of attention when she finally arrived at the White House in January 2022, the internet withstood the crunch. But Psaki got one thing right: Presidential pets have long captivated the public’s attention.

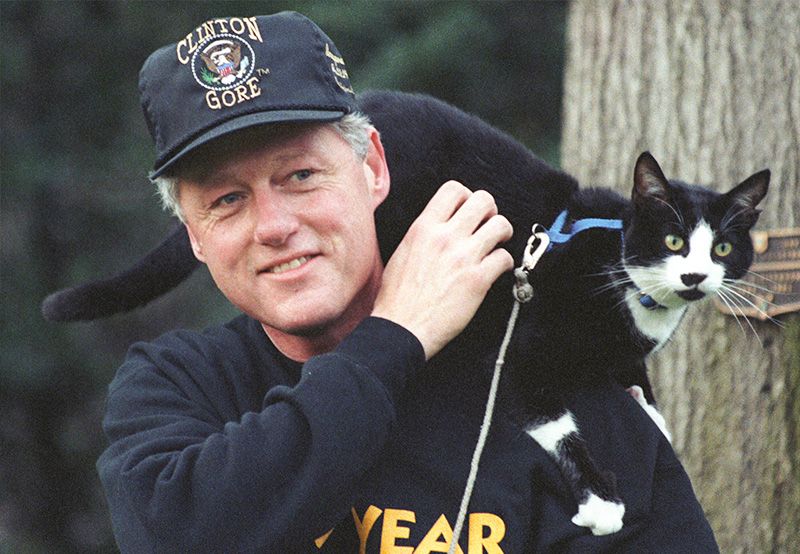

From Warren Harding’s Airedale terrier, Laddie Boy, and Franklin Roosevelt’s Scottish terrier, Fala, to the Bush dogs Millie and Barney and Bill Clinton’s cat, Socks, many White House pets have become household names.

Andrew Hager, historian-in-residence for the online Presidential Pet Museum, understands that not everyone shares the fascination.

“There’s always that contingent of people who are like, ‘Well, why do we care about the president’s dog? This isn’t really news,’ ” Hager says.

But the news coming out of the White House is often somber or upsetting, and the occupants of the Oval Office can seem far removed from regular folks. Presidential pets help break the gloom and make the president seem like a real person. They provide feel-good stories: During George W. Bush’s tenure, for example, “Barney Cam” videos presented a dog’s eye view of the holiday adventures of the popular Bush family terriers, Barney and Miss Beazley.

“When you’ve got all these other terrible things happening in the news, it’s nice to have a little bit of time to think about, ‘Oh, hey, there’s the president playing fetch with his dog,’ ” Hager notes.

“Pet-keeping humanizes the president and his or her family,” agrees Bernard Unti, a historian and communications strategist for the Humane Society of the United States, “because it’s such a common and endearing practice to so many millions of Americans.”

White House pets allow people to “have a bond with the president—at least in the sense that, ‘Hey, we own a pet, he owns a pet,’ ” Hager says. “This is one way that we actually get a chance to be like them—or that they get to be like us, I suppose.”

“Pet-keeping humanizes the president and his or her family because it’s such a common and endearing practice to so many millions of Americans.”

—Bernard Unti, a historian and communications strategist for the Humane Society of the United States

All the presidents’ pets

All of the presidents of the United States could fit in a school bus; there have only been a few dozen of them. Their animals, on the other hand, would need an ark.

The critters at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue haven’t always been companion dogs and cats: Early presidents had working animals, Hager notes. Hounds were for hunting; horses provided transportation. Yes, there were some early nonworking presidential pets: John Adams, our second president, had two pet dogs, for example. But Hager says presidential pet-keeping is generally “far more common now than it was in the early days.”

Wild animals and farm animals have passed through presidential hands. John Quincy Adams, president from 1825-29, had an alligator who lived in a White House bathroom. President from 1901-09, Theodore Roosevelt had a menagerie that included a badger, a macaw, guinea pigs, rabbits, five bears, a lizard, a pig, a pony, a zebra, a one-legged rooster and a hyena. In the 1920s, noted animal lover President Calvin Coolidge’s animals included a raccoon, a bobcat, a donkey, lion cubs, ducks, a wallaby and a pygmy hippo. (Some of these animals, including Roosevelt’s bears and Coolidge’s hippo, arrived as gifts and were rightly sent to the zoo.)

As late as the early 1900s, sheep and cows grazed the grass on the White House grounds. Cows supplied first families with milk and butter when no dairy companies served Washington, D.C.

By the mid-20th century, thanks to a growing recognition that wild animals belong in the wild and state laws banning the private ownership of wildlife, White House animals largely narrowed to dogs and cats. They also started coming inside, reflecting a nationwide trend spurred by improved flea medication and the invention of kitty litter. While wild animals at the White House are an intriguing part of presidential lore, we know better now, and it’s unlikely that a contemporary first family would be gifted or would accept a wild animal as a pet.

Political animals

Many White House animals have caught our eyes and captured our hearts, and some have even proved to be politically significant. The most memorable presidential creatures have included William Taft’s Pauline Wayne, a handsome black-and-white Holstein. Pauline was the last cow to live at the White House.

“Previous cows served primarily as milk producers at the Executive Mansion,” notes the White House Historical Association, “but Pauline was adored beyond her role as a dairy source.” When Pauline went missing for two days in 1911 while being transported by train to a dairy exposition in Milwaukee, several newspapers provided breathless coverage.

Harding’s Laddie Boy was the first of the White House pets to have a public identity, says Unti. The terrier had his own chair for meetings of Harding’s Cabinet.

“Laddie Boy was so synonymous with Warren Harding that when Harding died … people were really grieving,” adds Hager, “and newsboys around the country collected pennies, which were melted into a statue of Laddie Boy, which is currently at the Smithsonian.”

Then there was the raccoon gifted to Coolidge by a Mississippi man in November 1926, with the idea that the first family would cook and eat the animal for Thanksgiving dinner.

The president and first lady Grace Coolidge decided to make the raccoon a pet instead, naming her Rebecca. A house was constructed in a tree outside the Oval Office, and Rebecca also spent time inside the White House, where her favorite activity was playing in the bathtub with a bar of soap, according to the Library of Congress blog.

Rebecca attended social events with the first lady, vacationed with the first family and made an appearance at the 1927 White House Easter Egg Roll, gaining “quite a bit of fame” as her adventures routinely made the newspapers, the blog reports. But as a wild animal, Rebecca also exhibited destructive tendencies—digging up houseplants, opening cabinets and unscrewing lightbulbs. When the Coolidges departed the White House, they sent Rebecca packing to what is now the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

Franklin Roosevelt’s Fala, a Scottish terrier who arrived at the White House in 1940, was a lively dog who became Roosevelt’s near-constant companion, and Roosevelt recognized his public relations value. Fala traveled with the president on long and short trips by train, car or boat; he attended conferences and met world leaders, sometimes entertaining them with tricks. “His most impressive trick was curling his lip into a smile,” according to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

During the 1944 campaign, a rumor surfaced that Roosevelt had accidentally left Fala behind on the Aleutian Islands and had sent a U.S. Navy destroyer to retrieve him at great taxpayer expense. Roosevelt responded with what came to be known as the “Fala speech.”

He told a labor organization, “These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks on me, or my wife, or on my sons. No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course, I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks, but Fala does resent them.”

Roosevelt continued that when Fala heard the rumors about the retrieval that allegedly cost as much as $20 million, “his Scotch soul was furious!”—drawing laughter from the crowd. As Katherine C. Grier writes in her book Pets in America: A History: “Roosevelt realized that Fala made him more approachable, and White House public relations departments have been using presidential pets for this purpose ever since.”

Lyndon Johnson understandably caught a lot of flak in 1964 for picking up one of his beagles, Him (of the pair Him and Her), by his ears. The incident touched off a storm of protest in the form of phone calls and letters, and newspapers and magazines gave it significant coverage.

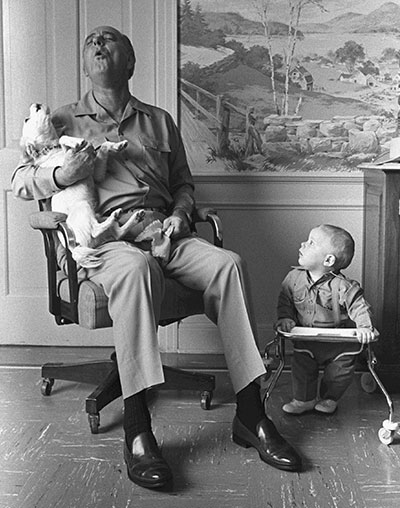

But Hager maintains that Johnson was a true animal lover. Johnson’s daughter Luci found a stray terrier mix at a Texas gas station on Thanksgiving Day in 1966 and named him Yuki, the Japanese word for snow. When he visited the White House, “Yuki won the President’s heart and became his faithful companion,” living with Johnson starting in August 1967, according to the LBJ Presidential Library.

A famous photo shows Johnson and Yuki “singing” together at the White House, with heads tilted upward and mouths wide open. After Johnson retired from the presidency, he recorded an album, Dogs Have Always Been My Friends, where he reflects on his lifelong love of canines and how happy he was that his daughter found Yuki. “Johnson just speaks so glowingly about this dog,” Hager says. “You can tell he just really loves animals.”

Modern times, modern pets

Today, Unti says, first families have settled into a style of pet-keeping that’s “truly reflective of our era. It completes the picture of domesticity at the White House, showing the lighter side, the family side, the human qualities, the humane qualities of the occupant of the office.”

Recent first family choices reflect a number of important trends in pet-keeping and public sentiment toward animals. Naturally, presidents and their families no longer keep wild animals as pets. Recent White House pets have been spayed or neutered, reflecting the growing nationwide acceptance of the practice. Cats such as the Clintons’ Socks, the Bushes’ India and now the Bidens’ Willow have cemented felines as one of the nation’s most popular pets. The Obamas, keeping a promise to their daughters to get a puppy following the 2008 election, accepted Portuguese water dog Bo as a gift from Sen. Edward Kennedy and his wife. Bo came from a breeder (as did Sunny, a second Portuguese water dog in the Obama White House), which disappointed some shelter advocates and sparked discussion of the merits of shelter adoption vs. the acquisition of pets from breeders.

Most recently, in a milestone of presidential pet lore, the German shepherd Major, adopted by the Bidens in 2018 from the Delaware Humane Association, became the first shelter dog to live at the White House.

Major arrived with great fanfare, including extensive media coverage and a Zoom-powered “indoguration” party that raised money for his former shelter. Shelter and rescue advocates celebrated Major’s ascension to White House pet, but the story quickly grew more complicated.

Interviewed in summer 2021, Hager said, “I think what Major typifies is the rise of the rescue dog over the last 30 or 40 years—the push to ‘adopt, don’t shop’—and I think that’s great.”

Major highlighted the desirable dogs available at shelters and rescues, Hager continued. “You can find the dog that you want, and there’s a perfect dog out there for you waiting to be rescued somewhere.”

All of that is still true, but Major’s time at the White House proved to be short. After a series of biting incidents, Major was sent to Delaware in April 2021 for training. Following a brief return, the White House announced in December that Major’s permanent home would be elsewhere.

“After consulting with dog trainers, animal behaviorists, and veterinarians, the first family has decided to follow the experts’ collective recommendation that it would be safest for Major to live in a quieter environment with family friends,” Michael LaRosa, a spokesman for first lady Jill Biden, said in a statement.

“I think the Bidens, who are longtime dog owners, showed just how much they love and respect Major by placing him with a family who could offer him a better environment. The White House is a stressful place to live or work. Many people can’t handle it. Major was apparently no different.”

—Helaine Olen, Washington Post columnist

The decision drew praise from Washington Post columnist Helaine Olen: “I think the Bidens, who are longtime dog owners, showed just how much they love and respect Major by placing him with a family who could offer him a better environment. The White House is a stressful place to live or work. Many people can’t handle it. Major was apparently no different.”

Perhaps disappointing to those hoping Major would usher in a new age of shelter pets at the White House, Major’s story does show that shelter dogs, like any other pet, need time and patience to adjust to a new home—and may eventually need to find a home that’s a better match.

Champ, the Bidens’ 13-year-old German shepherd, died in June 2021. Commander, a German shepherd puppy, arrived in December 2021 as a gift from the president’s brother and sister-in-law.

Willow, a former Pennsylvania farm cat whose path to the White House began when she jumped onstage while Jill Biden was speaking during a 2020 campaign stop, will need to navigate the same tricky path that tripped up Major.

“With any cat, moving to a new home can be a big deal, let alone a home that’s as vast and busy as the White House,” says Danielle Bays, HSUS senior analyst for cat protection and policy.

But Bays says Willow’s early signs are encouraging. In photos the White House has shared, Willow looks curious and comfortable, whether she’s looking out the window or just lying in the middle of the floor. She’s not hiding; her ears aren’t back; she doesn’t look concerned or stressed.

“That was really nice to see,” Bays says. “She’s probably going to be holding her own press conferences pretty soon.”