Women’s movement

Philadelphia shelter blazed trails with all-female leadership

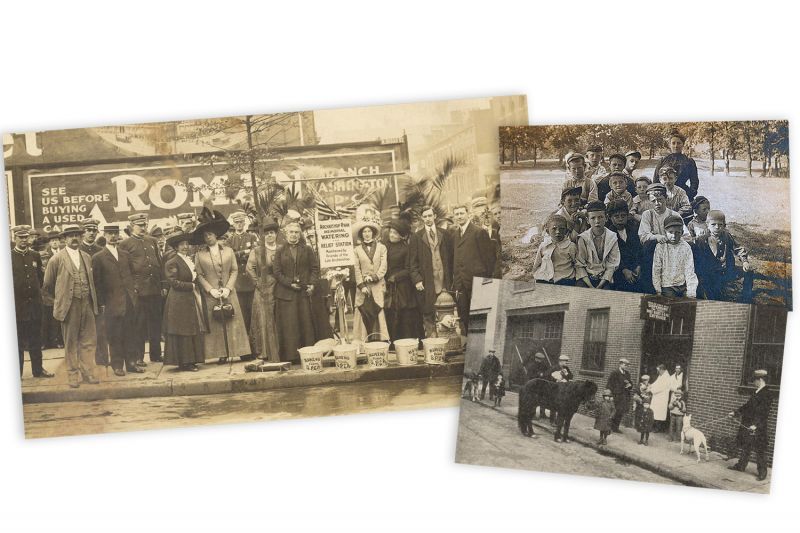

Nearly 50 years before some women were granted the right to vote, 30 women spearheaded the Women’s Branch of the Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals—and 150 years later, women still drive the animal welfare field.

In the City of Brotherly Love, it was sisterly compassion that paved the way for modern animal sheltering in America.

In the mid-19th century, the treatment of carriage horses in Philadelphia was often so brutal, Caroline Earle White avoided certain streets altogether as a child. Later in life, that same compassion led her to spearhead the establishment of the Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (PSPCA) in 1868. But while White secured funding and helped organize the society, in keeping with the norms of the times, it was her husband who was elected to serve on the board of directors.

That didn’t stop White from taking a leadership role to protect her city’s animals. She enlisted other women to found the Women’s Branch of the PSPCA.

“That’s what created our organization: The women saying, ‘We want to do more,’” says current chief executive officer Catherine Malkemes.

The organization started with 30 women, nearly 50 years before they gained voting rights. And just like the suffragettes, their work attracted public scorn and criticism. In the organization’s first annual report, White mentioned “a vast number of attacks” from Philadelphia and New York daily newspapers, “in which misrepresentation and ridicule constituted the chief weapons of our opponents.”

Undeterred, the Women’s Branch tackled a bevy of cruelty issues, initially focusing its efforts on the most visible victims of the time—the abused horses and abandoned dogs in the streets.

At the time, stray dogs were considered little more than a public nuisance, and city “pounds” reflected that attitude. In the organization’s first year, White and her team successfully petitioned the mayor to found the Shelter for Dogs and Other Animals with the goal of reuniting pets with their owners or finding them new homes. “They founded the concept of an adoptions program,” says Malkemes.

The Women’s Branch petitioned for basic shelter standards—including providing animals with food and water—at municipal facilities and convinced officials to end the practice of keeping shelter dogs continually muzzled, says Malkemes. They also erected drinking fountains for carriage horses and dogs throughout the city.

At the end of its first year, the Women’s Branch had grown to 400 members and gained a reputation for being “more assertive and hard-nosed than its parent institution,” says historian and HSUS senior policy adviser Bernard Unti.

Its impact continued to expand over the following decades with programs to help sick or injured cats, provide veterinary care for dogs and farm animals, and bring humane education to local children, who joined the organization’s “Bands of Mercy” to report animal cruelty. With White at the helm, the organization took on more controversial issues, as well. White battled with scientists over the use of shelter animals in laboratory research and founded the American Anti-Vivisection Society in 1883. She pushed for more humane treatment of cattle during transport, helped secure convictions of pigeon shooters and challenged fox hunting.

“White was a powerhouse,” says Unti. “She is someone who’d be very comfortable in the modern world of animal advocacy. She successfully navigated the gender-based constraints of her era to level a strong challenge to animal cruelty.”

White died in 1916, but the organization she co-founded—now named the Women’s Humane Society (WHS)—continues her legacy of serving the people and animals of greater Delaware Valley. The only open-access animal shelter in Lower Bucks County, WHS rehomes about 4,000 animals a year, while its Caroline Earle White Veterinary Hospital provides low-cost spay/neuter and other veterinary care for over 10,000 animals annually.

“I think that our founders … believed that this was not an animal problem, it was a humankind issue,” says Malkemes. “I think the same is true today.”

Just like their predecessors, WHS staff members tackle animal homelessness and cruelty from many angles. Along with sheltering and low-cost vet care, they provide dog training classes to the public, advocate for stronger animal welfare laws and educate their community about humane issues.

Through relationships with schools and Scout groups and a shelter-based read-to-the-animals program, WHS also continues to engage the younger generation in the cause of animal protection. Area children hold shelter collections at their birthday parties in lieu of gifts and regularly engage in schoolwide penny drives, says Malkemes.

And the tradition of female leadership? That’s going strong, with a rule in the WHS bylaws that its board of directors be fully comprised of women. “Our board of directors over the years has really been committed to the word ‘women’s’ in our name to honor the legacy of the women who founded the concept of rehoming animals,” says Malkemes. “A lot of people do not realize the role that women played [in animal protection] back in the late 1800s.”