How-to: Design a new animal shelter, Part 1

Sheltering and design experts share their top tips for planning and designing a new shelter facility

Once upon a time, planning an animal shelter was simple. A city or county simply erected a cinderblock building on the least valuable piece of land the municipality owned—typically next to the town dump—and finished it off with a concrete floor and chain-link kennels.

Fortunately, the field of animal sheltering has progressed, and so have the facilities. Modern shelters are designed to promote animals’ physical and emotional health, and appeal to the public. They’re community resource centers, often featuring veterinary clinics, training classes and summer camps for kids.

But as the expectations for animal shelters have risen, so has the complexity of planning a new facility.

Jackson & Ryan Architects in Texas has designed a variety of buildings, including colleges, churches, multistory apartment complexes, sports stadiums and animal shelters. Of all these, shelters are “by far the most challenging,” says associate principal Kim Raborn Hanschen. “It’s like mixing a hospital and retail environment with educational components—and then you have creatures living 24/7 inside them.”

Add tight budgets and passionate opinions about what an animal shelter should look like and the purposes it should serve, and you have the ingredients for a project that can overwhelm even the most determined shelter leadership team.

To plan a shelter that will meet the needs of your animals, your staff and your community, you need a big-picture vision as well as keen attention to the small details, says Shelly Moore, CEO of the Humane Society of Charlotte in North Carolina. You need to set budgets, manage expectations and practice the art of compromise. At the same time, you need to look into the future while also working to address the problems of the present.

It’s a tall order, Moore admits, but it is achievable. And it starts with tapping the growing field of knowledge about sheltering best practices and design.

In Part 1 of our shelter design series, sheltering and design experts share their top tips to help you start planning for the shelter of your dreams.

Get your house in order

When you’re operating out of a ramshackle facility, it’s easy to picture a new building as the solution to all your problems. Heather Lewis with Animal Arts, an animal care architecture firm in Colorado, frequently meets shelter clients with that expectation. The analogy she shares with them: You don’t build a house because your marriage stinks. You work on the marriage first.

That means taking a good look at your operations before you start planning a new facility. You may first need to focus on refining your standard operating procedures, recruiting and retaining staff, building your board, expanding volunteer and foster care programs, or improving workplace culture.

“Get your operations down, and if you can do that in a crappy building, you can absolutely do that in an amazing new and sparkling building,” Lewis says. “You don’t want to take that baggage with you.”

A clear-eyed view of your organization’s leadership and goals is also essential, says Moore. “I’ve met people who are building a new building, and they’ve already jumped to the step of finding an architect when they don’t have a functioning board, a strategic plan or a vision.”

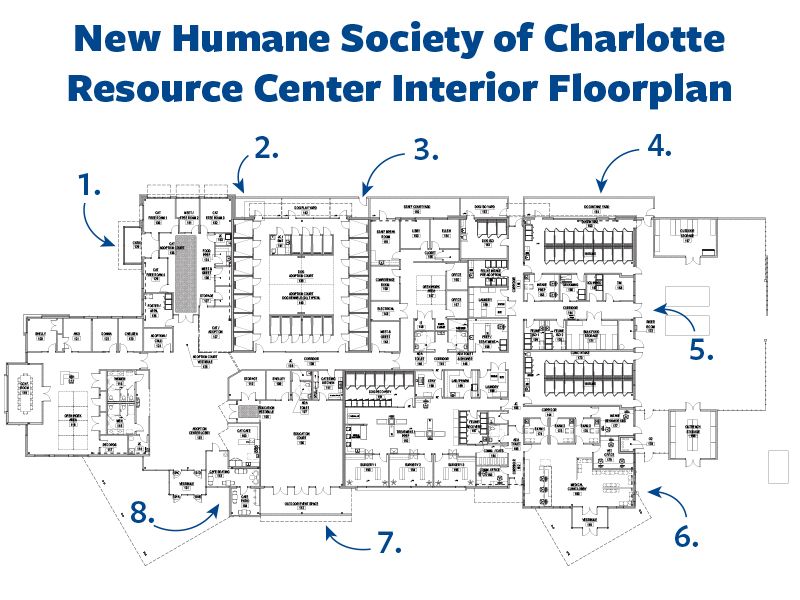

1. Catio area to provide outdoor enrichment for adoptable cats. 2. Indoor adoption counseling areas and areas for pet meet and greets. 3. Indoor, climate-controlled, low-stress kennels. 4. Segregated animal housing to provide a low-stress environment to dogs transitioning to pre-adoption holding. 5. Climate-controlled storage areas. 6. New clinic area to provide basic veterinary services to community pets. 7. Education court to provide space for community educational and recreational opportunities; training for animal welfare professionals; and socialization and pet training. 8. Cat cafe to provide a community space for visitors and showcase adoptable cats.

Consider alternatives

An early decision you’ll likely face is whether you need to build a new facility or make the best of your existing one. If your main challenge is simply lack of space for the number of animals you’re taking in, your money may be better spent on expanding foster care, spay/neuter and pet owner support programs, says Lindsay Hamrick, director of shelter outreach and engagement for the Humane Society of the United States.

In other cases, the need for a new facility may be clear-cut. “You’d be surprised how many clients have buildings in floodplains,” Lewis says.

Many shelters today are still operating in facilities built 30 to 50 years ago, with concrete or wood frames, vastly undersized for their needs and with decades of patchwork fixes. “Nothing works well, there are massive inefficiencies for the staff and a lot of stress for the animals,” says C. Scott Learned, founder of Design Learned, an animal care facility engineering and interior planning firm in Connecticut. In such cases, renovating the building to meet today’s standards can cost as much or more than new construction.

There are exceptions, Lewis adds. “Ugly but sturdy has potential. We can fix ugly.”

If your facility was built to commercial standards, has good bones and is of adequate size, renovation may make sense. In 1998, Lewis worked with a Nebraska shelter to renovate a former grocery store and turn it into an animal shelter. A few years ago, she helped remodel the space again. “Now it’s a modern shelter and functioning well for them,” she says.

Look for interim solutions

To get a facility that will serve your organization well, you should plan to spend at least two years on planning and about one year on construction, says Chad Ackerman, chief operating officer of the KC Pet Project in Kansas City, Missouri. For some organizations, the process will take much longer, so it’s important to have patience, adds Moore. “It seems like it’s so urgent, and it is a lot of times, but it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Building cheap and fast is one of the most common mistakes Lewis sees in shelter building projects. Instead of rushing the process, she encourages shelters to search for interim solutions to help meet current needs. “If education is a big priority, you can build or rent space somewhere else. You can knock out space for a MASH clinic while you plan a campaign to replace the entire shelter.”

When the KC Pet Project started planning a new building in 2016, it was in desperate need of more space. So the organization bought and retrofitted four double-wide construction trailers to serve as veterinary care space and isolation housing for sick dogs and cats. A donor purchased a former dentist office, which the organization used to house their behaviorally challenged dogs, providing a calmer environment where the staff canine behavior team could give them more one-on-one attention. It wasn’t perfect, Ackerman says, but these measures bridged the gap during the years it took to plan and build a new facility.

Form your team

Planning a new facility isn’t a solo venture, and you need to recruit the right people to lead the key components. For starters, Moore says, you need a person who understands the construction industry.

Moore found her future building committee chair on an airplane when she was seated next to an executive with a construction company. She spent the rest of the flight telling him about the Humane Society of Charlotte and its need for a new facility.

When forming committees for the KC Pet Project’s building project, Ackerman, an experienced preconstruction project manager, looked for “open-minded big thinkers mixed with animal shelter folks and fundraisers.” People with the right skills and experience are out there in your community, he says. A good way to find them is to survey your staff, volunteers and donors to learn about their skills, backgrounds and connections.

Architects are another essential part of the shelter planning team. Hanschen recommends choosing one who specializes in shelter design and will know about the latest standards for animal housing, the materials that will withstand hard-core use, disease control and other considerations. “This is something where you really need expertise, especially at the early stages, and even if they’re just consulting on the project,” she says.

If your budget allows, Moore advises hiring an owners’ representative to negotiate with contractors, architects, engineers and the design team. It’s a significant expense, she admits, but it will save you and your staff a tremendous amount of time and frustration. When searching for an owners’ representative, Moore and her team interviewed several candidates before choosing a local professional with long experience managing building projects. “He was vetting and fielding all the requests,” Moore says. “That took a lot off me.”

Assess your needs

Are your animal intakes expected to increase in the coming years? Do all your staff members need their own offices? Will you be offering spay/neuter or wellness care for community pets?

These are the types of questions you need to consider during a needs assessment, an essential first step in shelter design. If you’re not planning around your current and projected future needs, “you can come up with the wrong physical solution,” Lewis says.

Hanschen recommends starting the needs analysis by soliciting multiple viewpoints—from your staff, board members and your community—and encouraging people to think outside the box. Perhaps that doggie rehabilitation pool or that Starbucks kiosk in the lobby won’t make the final cut, but “you have to figure out what the dream is first and then start to refine,” she says.

When it comes time to prioritize your needs, use your organization’s mission and vision as a guide. “Defining what’s most important to you is so key,” Lewis says. “You can’t be all things to all people.”

You also want to talk with other nonprofits and agencies in your area to develop a cohesive community plan for meeting animal welfare needs. When Lewis began working with the nonprofit Atlanta Humane Society in Georgia to design a new facility, she learned that the county municipal shelter was in the process of building a 55,000-square-foot facility. Atlanta Humane wanted to focus more on community programs, helping pets and their families outside shelter walls.

The new shelter, which opened in 2022, features a state-of-the-art shelter medicine area, housing for dogs and cats in need of extra behavioral care, and a bilingual resource center. It’s also 20,000 square feet smaller than the previous facility.

Atlanta Humane didn’t need a large building for housing more animals, Lewis says. “They needed to be out in the community with their resources as a nonprofit organization. They can work to support the county shelter and also do the projects that are unlikely to get approved for government funding.”

Land in the right spot

Many shelters don’t just need a new building—they also need a place to put it. And depending on the local real estate market, a land search can be one of the biggest challenges of planning a new facility.

Before searching for suitable land, Learned recommends consulting a shelter design expert to help determine the size and type of property you need. While rural areas are less expensive, he says, “for most shelters, it’s better to be closer to centers of populations.”

Lewis agrees. A common mistake shelters make is purchasing a rural parcel with no utilities, she says. “Then they have to pump a septic system until the cows come home. It’s a huge operational cost every month.”

In some cases, finding property that you can afford and that will meet your needs isn’t enough: You may also need to navigate zoning issues and special use permits. To forestall objections from neighboring landowners who may envision a “rat-infested kennel building,” Moore also recommends reaching out to the community early in the purchase process.

That’s what the Humane Society of Charlotte did after its yearslong search for suitable property ended with the purchase of a 17-acre parcel on the west side of the city. The back of the property adjoined a residential neighborhood, so after submitting a rezoning request, shelter staff held neighborhood meetings to explain their vision of a modern animal resource center that would be an asset to the community. In this way, they garnered their neighbors’ support for the project.

Learn by example

No matter how many episodes of This Old House or Property Brothers you’ve watched, you’ll need to educate yourself on the basics of shelter design. The best place to start is by visiting other shelters.

While touring shelters, Moore gave her team a list of questions to ask and things to observe. Along with gathering hard data—such as building size and cost, monthly utility bills, staffing levels and the like—they chatted with staff and volunteers to learn what they liked (and disliked) about their facilities.

Ackerman recommends visiting shelters in various parts of the country to see how their buildings have held up in different climates. “Take out your cell phones and take pictures of floors and wall coverings,” he says. “Those are things that will require maintenance and start to show wear the soonest.”

Other shelters can provide inspiration as well as cautionary lessons. “One shelter I won’t name put floor drains in the cat room, which was great except volunteers swept litter down the drains with water,” Ackerman says. “Our floor drains are capped in the cat area.”

Read Part 2 of our shelter design series for tips for balancing the needs of your animals, your staff, your community and your budget.

Document