Walking a mile in the other veterinarian’s shoes

Shelter vets and private practitioners can save lives through collaboration

Veterinarians working in the animal sheltering field know all too well the issues of animal homelessness and overpopulation: the puppy relinquished for chewing up the furniture; the geriatric dog whose owner couldn’t afford to treat the medical conditions related to aging; the stray intact dog brought in by a Good Samaritan after being hit by a car; litters upon litters of kittens.

The HSUS and the ASPCA estimate that 6 to 8 million dogs and cats enter shelters in the United States each year. In Southern California, where I work as a professor of shelter medicine in the veterinary college at Western University of Health Sciences, animal shelters in Los Angeles and Orange counties took in nearly 140,000 cats and dogs in 2015. Although still very high, their annual intake has declined considerably over the past decade, in part due to widespread spay/neuter efforts. But there’s still a lot of work to do, and achieving a high degree of success will require a collaborative effort.

Too often, shelter veterinarians find themselves at odds with private practitioners. Sometimes the shelter vets feel like they are viewed in a negative light because recently adopted animals arrive at local private clinics with varying degrees of illness—an unfortunate consequence of the nature of infectious diseases in group settings like shelters. Private veterinarians, meanwhile, feel like they’re looked down upon when people criticize their pricing and portray them as hard-hearted. Some people decry private practitioners because animals with treatable conditions are relinquished to shelters when the owners can’t afford medical care. Private vets love animals, too, but providing veterinary care is, after all, how they make their living.

A better understanding might happen with open lines of communication between shelter vets and private practitioners—but in my experience, those communications rarely happen. In many communities, partnerships between shelter veterinarians and private practitioners are few and far between. At best, there is simply a disconnect between the two—a lack of understanding and discussion. At worst, there is hostility. But rarely, it seems, do veterinarians in these two fields really know each other.

This is unfortunate, because we can help more animals and more people in our communities by working together—and it doesn’t have to come at the cost of profitability. As veterinarians, we all work to ensure animals receive appropriate medical and behavioral care. We all understand the importance and necessity of preventive health care. We all strive to educate our clients and staff on responsible animal care and husbandry. We all work to minimize stress for our patients, whether they are under our supervision in a clinic, shelter or at home. And of course, we can all agree that we want to reduce overpopulation and prevent animals from becoming homeless whenever possible.

Getting to know you

We could start by opening the lines of communication and getting to know one another. This first step is not always easy, and it’s important to realize that not every private practitioner or every shelter vet will be open to discussing ways to work together. That’s OK. Let’s start by focusing efforts on those in our communities who are open to talking. Once we develop the lines of communication, we can begin to find our shared values and goals and eventually move forward to developing meaningful partnerships.

In Southern California, our state veterinary medical association has been helpful in fostering relationships through its support of both private practitioners and shelter veterinarians. The Southern California Veterinary Medical Association (SCVMA) collaborates with multiple sheltering and nonprofit organizations, as well as veterinary hospitals, on events and outreach programs. The SCVMA offers free veterinary examination certificates to area animal shelters to pass along to their adopters. Participating SCVMA member hospitals redeem the certificates and provide a free first examination for newly adopted shelter animals. The program helps bring new adopters to the veterinarian, which can be the beginning of a healthy new life for the animal and a new client relationship for the veterinarian.

The SCVMA also works closely with nonprofit and sheltering organizations on community outreach events to help keep pets with their families and out of shelters. For example, the Amanda Foundation, a local nonprofit rescue organization, operates a quarterly free pop-up clinic in Watts, a low-income area with sparse access to veterinary care. Nearly 200 patients visited a recent clinic, where they received an array of veterinary services that included examinations, vaccinations, blood work, ultrasound, radiography, dental care and spay/neuter surgery. The SCVMA coordinated volunteer medical staff for the event, which included 21 local veterinarians, 27 veterinary technicians and nearly 40 student volunteers. By offering access to free and low-cost medical care, these types of clinics provide necessary preventive health care that can help families avert the need to relinquish a sick animal due to an unexpected financial burden.

The private vets who participate in the Watts clinic enjoy the chance to bring much-needed services to an underserved neighborhood with high shelter intake rates and a high incidence of infectious diseases like parvovirus. The community has no veterinary hospital, and many residents don’t have the money or access to transportation to take their pets to the few clinics in surrounding areas.

Meeting of the minds

Despite the existing programs that help both shelter vets and private practitioners in our area, there is still an overwhelming lack of communication and collaboration between the two groups. To help rectify this situation, Maria Sabio-Solacito, veterinary chief of staff for the County of Los Angeles Department of Animal Care and Control, hatched the idea of holding an interactive discussion between shelter vets and private practitioners, wittily titled “Sex, Lies and Medical Records.” (The “sex” in the title relates to the roots of animal overpopulation, and the symposium also touched upon the need for factual shelter data.)

The symposium, held at Western University in fall 2016, attracted medical staff from animal shelters, private veterinary hospitals and academia. In order to ensure a successful meeting, we tried to register participants from animal shelters and private practices in roughly equal numbers, and drew a crowd of about 80 people, including veterinary students. Topics ranged from shelter guidelines for standards of care to the One Health concept (a strategy for expanding collaborations among all health care providers).

Participants say the forum helped dispel some of the misconceptions that shelter and private veterinarians have about each other.

Allyne Moon, a shelter registered veterinary technician (RVT) and SCVMA trustee, who gave a talk on an RVT’s typical day, says some general practitioners were surprised to learn what goes on at modern shelters. “They really don’t realize that shelter medicine has gone beyond the hold-and-euthanize model of years ago,” Moon says. “Now we’re actually treating animals, and the animals are getting very good care at our facilities.”

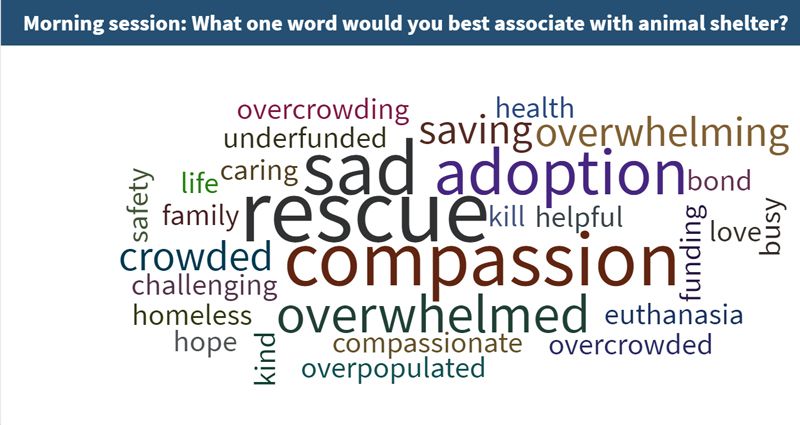

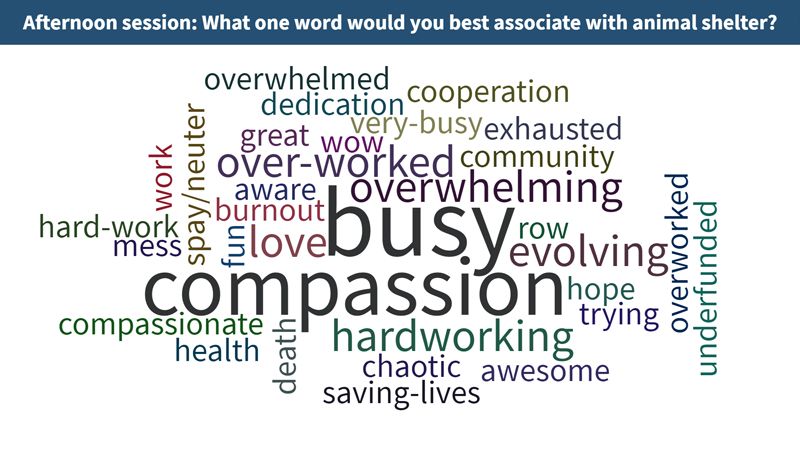

For a “word cloud” exercise, attendees were asked at the beginning and the end of the day what word they associate with animal shelters. Moon noticed that the morning session’s sentiments that shelters are sad places that don’t offer good medicine gave way to more recognition in the afternoon that shelters are busy facilities that could use more help. “That was very encouraging,” she says.

Presenter Jeremy Prupas, chief veterinarian for the City of Los Angeles Department of Animal Services, says the misunderstandings cut both ways. Private vets often don’t grasp that many shelter vets “are completely overwhelmed” by the number of dogs and cats coming through their doors—a point that Prupas emphasized in his talk. “We can’t physically see every single animal that comes in and do everything we want with them, because we just don’t have the time in the day to do that. A lot of what we do is triage.”

When private veterinarians treat shelter animals from an adopter or a rescue group, Prupas notes, “the thing that we want them to realize is that instead of making some snide remark to the owner or the rescue about how terrible we are at the shelter, maybe they can understand that we’re doing the best that we can.”

But at the same time, shelter staff have been known to make negative (and inaccurate) remarks about “money-grubber” vets and the high cost of private care, Prupas says. The bills for many operations he performs on shelter animals—from amputations to fracture repairs—never get passed to adopters, hiding the true cost of shelter veterinary care from the public, he explains. Even low-cost spay/neuter clinics are typically highly subsidized by the government or a private organization. This situation causes pet owners to compare apples to oranges, and to balk at private practitioners’ higher prices and wonder, “Why are you charging me $200 to spay my cat?” And when free or low-cost spay/neuter or vaccine clinics aren’t advertised as subsidized programs, Prupas adds, private vets can get irritated, wondering why their clients are getting “free” services.

The disconnect between the two camps is rooted in the perception that shelter veterinarians encroach upon private practitioners’ business, notes Diane Cosko, a private veterinarian and lawyer who attended the symposium. She felt that tension every time a spay/neuter mobile unit would pull up next to her hospital, offering free or low-cost surgeries, vaccines and microchipping. But coexistence is possible: Cosko says she’s changed her business model to focus on other services, and now she thanks the mobile unit “for coming around and forcing me to think outside the box.”

Prupas says his two main takeaways from the symposium were that shelter vets need private vets to back them up on their work, and private vets need shelter vets to do a better job of explaining how veterinary medicine works financially. “It’s not just what we want them to do, it’s what we can do for them,” he says. “Nobody wants to be adversarial; there’s no benefit to that.”

Sabio-Solacito agrees: “That’s one thing I would like people everywhere to know about animal sheltering: We’re not in our own world. We’re interconnected, right?” Many private practitioners are eager to help shelters—by working to end pet homelessness, for example—but they’re not sure how to get involved, she adds.

The issue of poor communication led to some lively discussions at the symposium, Prupas says, with shelter vets encouraging private vets to call or email if they have a question about the treatment an animal received at the shelter. Participants’ other ideas for improving communication included holding more events in the future that allow discussions to continue in a judgment-free environment; developing a contact list of local shelter vets and private practitioners; and having local shelter and private vets hold open houses so staffs can visit and learn more about each other. We hope to continue these conversations by holding similar events throughout the greater Los Angeles area in the future.

While we realize we may not have attracted those veterinarians who are less interested in collaboration, we did reach many vets and technicians who were willing to talk and wanted to learn from each other. We were also able to educate future veterinarians on the topics of animal overpopulation and homelessness, and how and why veterinarians from different fields should collaborate to help resolve these issues.

Carissa Jones, a veterinarian with LA County Animal Care and Control who helped organize the symposium, says it was “helpful on both sides.” She had initially found herself getting frustrated with community vets over issues such as the transfer of medical records but came to realize “they’re not the problem. The communication is the problem.”

Animal Sheltering’s James Hettinger contributed to this article.