Why we need cost of care laws

When pet owners are charged with cruelty, shelters and rescues often pay the price—literally

In February 2020, police in Boyle County, Kentucky, serving an eviction notice found two dead and 18 malnourished horses on a farm. Shortly after, Boyle County Animal Control seized the horses.

It was a major cruelty case for the local government, one that would require extensive resources—and one that would quickly get even bigger. Police continued to investigate the property, leading to the seizure of an additional 24 horses two days later.

The horses suffered from various medical issues including anemia, dehydration and upper respiratory infections, says Danville-Boyle County Humane Society. Some had been standing in stalls filled with over a foot of waste; others had coats matted in manure. Some of the horses were in such a poor state they had to be euthanized, while others were reclaimed by previous owners and current owners boarding them at the farm. All told, Boyle County officials were left with 35 horses in their care indefinitely.

Boyle County Animal Control has a unique partnership with the Danville-Boyle County Humane Society, a nonprofit organization. The two entities work in collaboration and share resources and even a building. Their collaboration would be crucial in surviving the coming weeks. Kentucky is one of the few states left with no “cost of care” law, which left the local government financially responsible for the horses while the cases proceeded.

“These cases are very real. They have a huge impact on communities, and ultimately that falls back on taxpayers.”

—Todd Blevins, HSUS state director for Kentucky

The burden of care

Cost of care laws (also referred to as bonding and forfeiture laws) vary by state, but they ideally mandate a hearing after animals are seized from an alleged neglect or cruelty situation to secure payment for the animals’ care. During the hearing, the owner either posts a bond upfront for the cost of caring for the animals or forfeits ownership of them. Either the seizing agency or prosecutor must provide sufficient evidence of cruelty, and defendants can present their side during the hearing.

In states without cost of care laws, animals are often forced to live in limbo while a court case proceeds. Since animals are considered the owner’s property, they can’t be adopted into new homes until they’re surrendered by the owner or legally forfeited after conviction. This means animals are often held for months or years, all the while municipal shelters and nonprofit rescues foot often exorbitant bills to house, feed and vet the animals. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused even more scheduling setbacks in criminal cases, increasing the amount of time animals may be living in shelters and rescues.

States without cost of care laws may require owners to reimburse the expenses after a conviction, but Ann Chynoweth, senior director of animal cruelty and fighting at the Humane Society of the United States, warns that this system doesn’t work. By the time a conviction is secured, shelters and rescues may have already spent tens of thousands of dollars caring for the animals. If defendants can’t pay these fees, the financial responsibility is still in the hands of shelters and rescues.

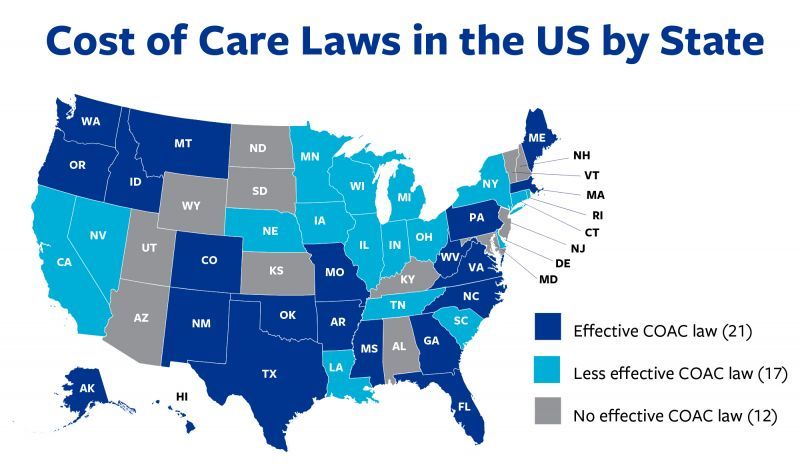

Currently, 38 states have cost of care laws, but they vary widely in their effectiveness, says Chynoweth. Chynoweth says 21 states currently have strong cost of care laws, which provide for the care of seized animals or their disposition before the criminal case is resolved. On the other hand, 17 states have “less effective laws” and 12 states have “no law or essentially no effective law.” These laws may not set a specific deadline for when a hearing must take place or only apply during the appeals process.

Large-scale seizures, in particular, highlight the need for cost of care laws. Authorities investigating animal fighting operations or puppy mills can find themselves with dozens or even hundreds of animals on their hands. These cases can be incredibly resource intensive from the start: Not only do seized animals need housing, food and enrichment for the long haul, but they often suffer health and behavioral issues. Placement into foster homes while a case is pending is not always feasible, and even the best-run shelters can be a stressful environment for animals long-term.

The community can also suffer the impacts of these cases: Shelters and rescues that are financially drained from caring for seized animals may be unable to provide other vital services such as programs aimed at supporting pet owners in the community.

The high cost of caring for rescued animals can also deter law enforcement from pursuing cruelty cases in the first place, says Todd Blevins, HSUS Kentucky state director. As a result, animals may be forced to remain in horrible situations simply because there’s no funding for their care.

“There is no question that agencies are going to be more hesitant to tackle [large-scale cruelty] cases when there is every likelihood that they are going to have to pay tens of thousands of dollars and provide housing, veterinary care and so forth for an unknown period of time,” Blevins says. “These cases can drag on for months or even years.”

The need in Kentucky

Blevins is currently working to pass a cost of care law in Kentucky. The need is clear: In addition to the horse neglect cases in Boyle County, 42 dogs were recently seized from an alleged puppy mill in Breckinridge County. The animals have already spent 18 months at the county shelter, amounting to over $100,000 in expenses. The case is still ongoing.

“Breckinridge County is a rural, low-population county, so the toll of such a case can be especially damaging,” says Blevins. “These cases are very real. They have a huge impact on communities, and ultimately that falls back on taxpayers.”

Boyle County was relatively fortunate. The Danville-Boyle County Humane Society and Boyle County Animal Control cared for the horses for over a month before the owners agreed to surrender them. Within two weeks, all found new adoptive homes.

Fizzy Ramsey, a volunteer and former president of the Danville-Boyle County Humane Society, credits the help from the community along with the collaborative effort between the nonprofit humane society, law enforcement and the county attorney for the positive outcome.

In the end, the animals’ care amounted to over $20,000, but it could have been much higher. The horses stayed at the location where they were seized, and community volunteers shoveled waste out of the stalls to make them livable. Volunteers also brushed the mats out of the horses’ hair and exercised the horses. Donations of money, feed and halters helped tremendously, as well.

“You look back and it’s like, ‘How in the world did the stars align in this way? How did we survive this?’” she says.

While Ramsey is grateful the horses were eventually surrendered, she stresses that a cost of care law could have expedited the process, alleviating the stress on the organization and the horses themselves.

It “would have made our lives so much easier in terms of getting these horses the care that they required and the one-on-one attention that they needed by getting them out of an impounded environment,” she says.

At the state level, Blevins is optimistic the cost of care bill will pass next session. The bill has widespread, bipartisan support, including with the speaker of the house. Soon local governments, shelters, rescues and animals in Kentucky may receive a vital lifeline.