Columbus Humane’s Essential Care Center

Ohio animal shelter takes a holistic approach to pet and human welfare

Columbus Humane’s Essential Care Center, which opened its doors in June 2023, defies a simple definition. It’s a pet food pantry. It’s a veterinary clinic. It’s a workforce training program. Soon, it will offer human health services.

At its heart, the center is about meeting the needs of pets and people—even when those services go beyond what a traditional animal shelter might offer.

When families are struggling, “it’s never just one thing,” says Rachel D.K. Finney, CEO of Columbus Humane. There’s housing insecurity, food insecurity, unreliable transportation, lack of access to health care. “It’s all of those things, and they can’t be separated. If pets are family, then everything impacting the family is impacting the pet.”

Founded in 1883, Columbus Humane is a privately funded shelter with a long history of serving pets and people in Central Ohio. The concept for a center that would meet a broad range of needs came during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. As staff worked day in, day out to distribute huge amounts of pet food to the community, they realized a dedicated warehouse would make their work easier and more efficient.

“At the same time,” says Finney, “we were absolutely bombarded by requests for veterinary support and services for owned animals.”

So the project grew: If they needed a warehouse for pet food distribution, they might as well find a spot where they could offer affordable veterinary care. And if they were offering veterinary care, they might as well address the veterinary workforce shortage by training people as veterinary assistants.

To identify a location that would be accessible to the people and pets who needed services the most, shelter leaders worked with Humane World for Animals’ Pets for Life team to create community assessment maps. They chose a location in the city’s far south side, about 16 miles from the shelter, in an area with “tremendous poverty” and few resources for pet owners, says Finney. After a $6 million fundraising campaign, they broke ground on a 12,000-square-foot building, complete with a veterinary hospital, a spacious warehouse and a drive-through for pet food pickups.

In the first six months, the center provided veterinary care to 2,896 animals, distributed 382,607 pounds of pet food and 12,333 pounds of cat litter, and served 4,144 households through the clinic and the pet food pantry. And they’re just getting started.

In this edited interview, Finney speaks about the Essential Care Center’s approach, what comes next and how other organizations can adopt this model in their communities.

The Essential Care Center challenges our thinking about what an animal shelter “should” be—it’s not just adoptions and spay/neuter. Did you receive any pushback when you first proposed the center?

We have a strong emphasis on human welfare and human services at Columbus Humane. We were founded in 1883 to protect women and children in addition to carriage horses and other animals. We didn’t have pushback but more along the lines of, “This is a lot of people stuff!” But my mantra is, if your neighbor’s dog is skinny, please go check on your neighbor! It is a complex message though.

How do you help people understand that message?

The very best strategy I have for innovation and big-picture thinking is to go with what I learned from my children when they were toddlers. It’s the very simple question, “But why?”

Pets aren’t getting veterinary care. But why? Well, because their people can’t afford it. But why? Because of the declining workforce—while demand is going up, the cost of competitive wages is being passed along to end users. But why? Because these companies need to be profitable.

I really think when we ask those questions on repeat, as we look at the challenges our community faces, we find some commonality and some overlap. It’s never just one thing.

The center’s Rachael Ray Foundation Pathways to Careers in Animal Health, which trains people to work as veterinary assistants, is especially innovative. How did that come about?

It’s really getting at the roots of the challenges. I kept coming back to, “How will our veterinary community ever be able to meet the demand for services when we don’t have a stable workforce?”

We’re in our fifth cohort of students now. Many of our students have graduated from our program and gotten jobs as veterinary assistants. A number of them have enrolled in a veterinary technician program. That was the sign of ultimate success because we want to increase the number of registered veterinary technicians, which is a really critical need in our community.

How does the program work?

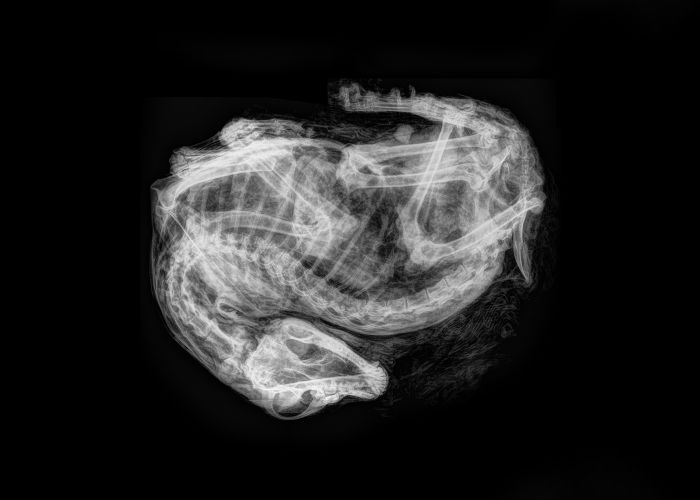

It’s a small group learning opportunity. We have no more than 12 students in a cohort. They have 40 hours of lecture in our classroom on-site and 30 hours of hands-on time working with clients and patients. Over their seven weeks with us, they’re building confidence. They’re learning all those foundational skills so that when they leave us, they go on to do 90 hours of training with a partner veterinary clinic.

What are the benefits of having students continue their training at partner clinics?

One, we wanted people to have access to what it’s like in other clinics, not just here at the Essential Care Center. Two, we wanted our partner clinics to have access to our graduates so they could make the first offer and get them employed as a veterinary assistant. Three, we wanted neighboring clinics to see us as a resource and a partner and somebody who’s helping them be successful.

How do you recruit students?

We specifically designed our workforce development programming around increasing diversity in the workforce. In Ohio, the veterinary profession is overwhelmingly women, overwhelmingly white. And there’s a lot of opportunity to invite others to the field. But initially we didn’t know the first thing about sourcing students.

We partner with Jewish Family Services and the Workforce Development Board of Central Ohio on our Pathways program. They help us source and interview our students, and they help promote the opportunity. Now we have a much more diverse workforce looking at our jobs.

That idea of partnership seems crucial to your approach. Can you talk more about that?

Collaboration is a core value for Columbus Humane, so we rarely do something by ourselves. Greater Good Charities is a huge resource for our pet food pantry, and the Pathways program was supported by the Rachael Ray Foundation.

We’re in the 16th—almost 17th—year of a partnership with the Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine. We’re a core rotation, so every veterinary student spends two weeks with us. We also have a social worker on site, and we work with the Ohio State University College of Social Work for interns. And we intend to partner with the university’s College of Nursing—they will be providing the nurse practitioner for our One Health clinic.

What role does your social worker fill at the center?

Our social worker helps clients navigate our organization’s offerings. So if they come in for one service, such as pet food, we can connect them to our other services, such as spay/neuter or other veterinary care. She also helps our veterinary clinic team counsel clients on euthanasia decisions, and she helps connect clients to various agencies that provide human support services.

The center embraces the One Health approach, which focuses on the interconnection between human and animal health. How does that work?

We’ll be hosting a nurse practitioner to provide baseline human health services. We designed our veterinary hospital with a unique exam room that would facilitate the human healthcare component.

What we’re trying to do is to champion whole family safety and healing and whole family care. We do that by making sure that all the mouths are fed in the household. We do that by providing on-site social work. We recognize that this strong connection for our community with pet healthcare is an amazing pathway for them to experience wellness care for themselves.

Do you have any tips for organizations that are contemplating a similar program?

Just like any innovative program area, you need to listen, really listen, to your community about what their needs are and where their needs are.

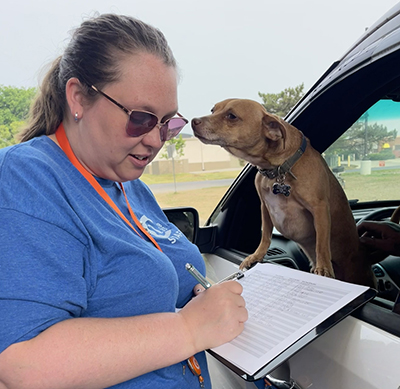

From a pet pantry perspective, install a drive-through! We have a porte cochere so you don’t get rained on. We also use little key tags like you get at the grocery store with your frequent shopper number. And our clients do not lose them. We know how many people are in the household, how many pets. We know how many people are coming through, how many products are going out. But forget about all the data. The key tags really make people feel a sense of connectedness and belonging, and that’s huge.

Also, we have pets dying of embarrassment all over the country—that is, their owners are embarrassed because they can’t figure out how much veterinary care will cost and are afraid to take their animals to the vet. So our services for veterinary care, including for sick or injured pets, are fixed, up-front pricing. There’s no, “Well, it depends on what diagnostics are used and what medications and if you have an E-collar and if you have go-home meds.”

Is the center one of your proudest achievements?

I’ll have been with the shelter 16 years this summer, and I recently announced that I'm leaving my position in June. I really wanted to go out on a high note. The Essential Care Center is the highest possible note I could come up with! Like how could it get better than this?

And while I recognize that it’s ambitious and probably a little bonkers, it is so beautiful and it has been such a gift to our community and to our staff to have a place for all of the services for owned animals. I think it’s a huge victory.