The power of one

Julie Morris of the ASPCA has spent 35 years helping pets and people

Even in her early days in animal protection, Julie Morris was thinking ahead.

In 1978, armed with a bachelor’s in zoology and a master’s in secondary education, Morris was working as a student teacher when her career path veered in a different direction. She left education to work as a shelter attendant at the Humane Society of Huron Valley (HSHV) in Ann Arbor, Mich.

“I’d never been to a humane society in my life, but the idea of working with animals appealed to me,” says Morris. Over 10 years, she worked her way up from kennel attendant to executive director.

It was during this time that she had one of the many “aha!” moments of her career. “We were turning down a lot of potential adopters,” she remembers. “Yet we were taking in mountains of animals—15,000 a year—litters and litters of puppies, purebreds, everything.”

Morris arranged for the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research to survey the people whose applications were denied. She discovered that many of these families had gone on to acquire animals through another source on their way home from the shelter that same day. Most of them acquired a new pet within a month.

“We learned that we hadn’t stopped people from adopting; we only stopped them from adopting one of our animals,” Morris says. “And most of those who did get a pet elsewhere hadn’t yet had them vaccinated, spayed or neutered, or seen a veterinarian—all services we would have provided.”

Drawing on the findings, Morris and her staff developed a friendlier method of talking with potential adopters. They were practicing what’s now widely known as an “open adoptions” approach. By the time she left the HSHV, adoptions had skyrocketed, and annual intake had fallen to 8,000.

Evolving Attitudes

Morris came to the ASPCA in 1990, starting out overseeing New York City’s official shelter and animal control services, which were run by the ASPCA at the time.

“Back then, we didn’t question or challenge euthanasia, and neither did the community,” she recalls. What’s more, “when I started, the ASPCA was almost exclusively New York City-focused.” That changed in part in 1995, when Morris started the shelter outreach department (today known as Community Outreach) as a vehicle to share resources—programs, grant funding, research and training—with shelters and rescue organizations nationwide. The department focuses on helping these organizations improve their practices in order to save more at-risk animals.

Over the years, Morris has seen the context of shelter work shift dramatically. There have been sweeping changes in public policy, increased sophistication in animal welfare advocacy and advances in cultural attitudes and technology. And the challenges facing shelters have changed, too: The numbers of animals entering shelters early in her career—many of them highly adoptable puppies and purebreds—have dropped dramatically, but the animals arriving are often harder to place.

Like many long-timers in animal welfare, Morris cites Hurricane Katrina as one pivotal moment of her career. She was in charge of the ASPCA’s outreach to shelters affected by the storm, assembling and overseeing a team of internal and external experts who organized and dispatched volunteers, coordinated the purchase and shipment of emergency supplies and established a grants program for recovery and rebuilding.

“Katrina was a wake-up call,” Morris admits. “It changed and improved the future for animals during disasters, and there’s been a lot of growth since then.”

Her collaborative personality has helped engineer alliances that benefit thousands of animals. For example, the Mayor’s Alliance for NYC’s Animals, a coalition of more than 150 rescue groups and shelters working to find homes for thousands of the city’s animals, was founded in 2003 with help from the ASPCA. Morris credits the Alliance for much of the progress that’s been made for New York City’s animals; during its first 10 years, the percentage of shelter animals euthanized dropped from 75 to 25 percent. Today, the city is close to a 90-percent live-release rate.

“We wouldn’t be what we are without Julie,” says Jane Hoffman, president of the Mayor’s Alliance. “Her years of experience dealing with the complexities of animal sheltering issues nationally, as well as her understanding of these issues in New York City, was key to our creation and accomplishments.”

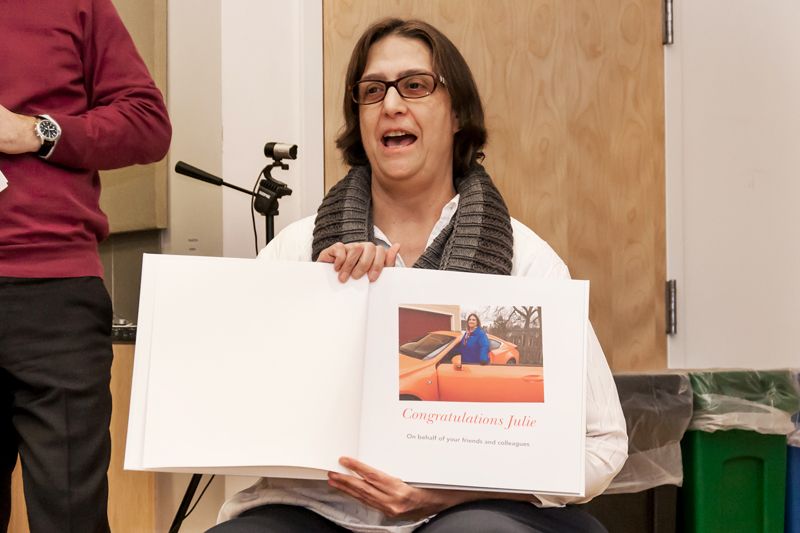

Morris—who recently celebrated 25 years at the ASPCA—now serves as senior vice president of the department she created, and she’s seen huge changes at the ASPCA and in the field as a whole. “Now we’re thinking outside of the box to find positive outcomes for at-risk animals. But even as we succeed, the challenges are constantly changing.”

“Julie saw that most animal shelters operate in a vacuum with little interaction to improve their operations,” says Pam Burney, vice president of Community Initiatives for the ASPCA: “[The Community Outreach department] is a product of her determination to remember there are still shelters that want to improve their lifesaving efforts and are eager for help.”

Building Bridges

Today, in communities and organizations supported by the ASPCA—which is celebrating 150 years in 2016—Morris and her team challenge shelters to provide measurable and sustainable change for at-risk animals. The team operates and supports safety net programs designed to keep pets and families together, tracks and collects data that helps shelters evaluate their progress, and encourages municipal and nonprofit sheltering and rescue groups to work together.

“Julie has shaped my thinking about animal welfare,” says Joe Elmore, CEO of the Charleston Animal Society in South Carolina. “She taught me how to look at animal flow as a community dynamic, not just an organizational dynamic, and that it’s in the best interest of larger organizations with higher capacity to assist smaller organizations.”

In her spare time, Morris nurtures an eclectic taste in music that spans Bruce Springsteen to Rodrigo y Gabriela to classical cello. Her most obvious hobby—obvious to anyone who has ever been to her Manhattan office—is her collection of more than 200 Pez dispensers.

Her Pez collection aside, Morris’s biggest joy is working with “an incredible team, both within and outside of the A,” and she plans to keep doing just that. With 35 years in animal welfare and more than a few natural (and unnatural) disasters behind her, she intends to keep up her lifesaving work for a long time.

“I still have a lot of energy,” she says, “and I simply love my job.”